Introduction

Aside from a few recent economic shocks—such as the sudden collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in March 2023 and the rapid emergence of advanced artificial intelligence (AI) systems—a sense of relative normalcy has settled over much of the economy following the COVID-19 pandemic. Unemployment rates are low, concerns about the Great Resignation have passed, supply chain disruptions have decreased, and many walkable urban and urbanizing suburban areas are thriving.1 The fate of downtowns is an unfortunate exception. Uncertainty and fear about their economic future is almost as prevalent as at the peak of the pandemic.2

The most apocalyptic visions of the collapse of American downtowns are not inevitable, nor are they particularly novel, as Tracy Hadden Loh and Hanna Love recently wrote.3 But even if downtowns are not destined to be objectively worse off than they were before the pandemic, they will certainly be different, and public and private sector leaders are trying to anticipate and shape their direction. Nearly every mayor of a large city is working on a downtown revitalization strategy, often with an eye toward a more balanced mix of office and residential real estate. Businesses continue to reassess their remote work policies and, accordingly, their office real estate footprints. And real estate developers and investors are rethinking their portfolios and strategies in response.

Real estate is the largest asset class in the U.S.... Changing how real estate is done and by whom could help ensure economic recovery in American cities and regions is more inclusive

As city leaders reevaluate the purpose and potential of their downtowns, they are doing so with an increasing recognition that progress on racial equity and economic inclusion is essential to the future vitality and vibrancy of their cities as a whole. Yet even as the connection between inclusion and economic performance has been clearly established, progress has stalled or worsened in many communities.4 And where economic indicators have improved, this progress has often been a result of whiter and wealthier residents moving in and/or the lowest-income people of color being displaced rather than a result of advancements in the status of existing residents of color.5 However, recent research indicates that it is possible to advance economic inclusion and increase prosperity at the neighborhood level.6

City leaders seeking to advance shared prosperity can employ a variety of interventions, and they should be putting efforts to help shape private sector real estate development at the top of that list. The decisions that real estate developers make—where and what to build, which firms to partner with, how spaces are designed, and how developments are positioned relative to the surrounding community—have a profound impact on which people and communities benefit from the built environment. In fact, real estate is the largest asset class in the U.S., accounting for about 43 percent of private assets, and commercial property transactions alone total about $750 billion annually.7,8 (For context, in 2019, state and local governments nationwide spent a far slimmer amount estimated in the tens of billions of dollars on subsidies to coax firms to relocate or expand.9)

With these kinds of numbers, it stands to reason that changing how real estate development is done in cities, and by whom, could help ensure economic recovery in American cities and regions is more equitable and inclusive than—if the past reveals anything at all—might otherwise be the case.

The conditions may be ripe for such a shift. Feeling rising pressure—both from external and internal sources—to contribute to economic inclusion, several developers in the past several years have reached out to the Brookings Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking seeking guidance on the issue. They have wanted to explore some of the following questions: If inclusion is a stated objective of a development project, how should it be defined and what specific outcomes would constitute success? What strategies can developers use to produce those outcomes? What new types of partnerships might those strategies require? What is the business case for making investments in inclusion?

Conversations with these development teams revealed that, while increasing numbers of real estate developers may be “inclusion curious,” few are actually guided by inclusion goals in their work. A 2020 report by the Urban Land Institute found that only 12 percent of developers were “regular adopters” of social equity practices—and the extent to which even those developers employed a breadth of inclusion practices (or had metrics for assessing their effects) was likely even more limited.10 The narrow uptake of inclusion-oriented practices among developers is striking insofar as many city and regional economic development organizations in recent years have made new efforts to define and quantify economic inclusion and to shape the behavior of key industries—including real estate development.

Developers know that their projects need to generate, not just rely on, urban vitality—and that requires engaging and supporting existing residents...city governments and neighborhood organizations alike are more aware than ever that a thriving downtown is crucial to overall fiscal and economic health, so they may be more open to collaborating with developers who are willing to bet on their urban cores.

This report is motivated by the clear need for a different model for urban real estate development.11 But it is also motivated by the idea that, amid the post-pandemic reckoning about the future of downtowns, there is also an opportunity to establish a different model. This opportunity is a result of, on the one hand, developers recognizing that they can no longer depend on a daily inflow of commuters to fill their offices and patronize businesses in their developments. Developers know that their projects need to generate, not just rely on, urban vitality—and that requires engaging and supporting existing residents. On the other hand, leaders in city governments and neighborhood organizations alike are more aware than ever that a thriving downtown is crucial to overall fiscal and economic health, so they may be more open to collaborating with developers who are willing to bet on their urban cores.

The goal of this report

Despite a growing focus in the public and civic sectors on economic and racial inclusion—and the significant influence that real estate could have on each—there are few frameworks that define inclusive development for private, for-profit actors. Existing frameworks tend not to be informed by industry, and therefore they tend not to reflect the financial and regulatory constraints under which developers operate. Moreover, they often focus on just a few aspects of inclusive development, such as affordable housing or construction workforce diversity, rather than illustrating how a developer could assemble a comprehensive portfolio of inclusion investments for a specific project.

This report seeks to address these gaps, specifically in the context of large downtown and downtown-adjacent developments. Based on evidence from the existing, albeit limited, literature and interviews with developers of several large catalytic projects, it argues that the status quo for real estate development needs to change: traditional (predominantly white and male) developers need to adopt different practices, a more diverse range of people and organizations need the capability and capital to do development, and both the public and nonprofit sectors—including community organizations—must engage with developers in more effective ways (see Table 1).12

This report provides guidance to move the field toward these ends, with a focus on the following:

- Addressing knowledge gaps. To the extent that some developers are already motivated to invest in inclusion but unsure how best to do so, we lay out a framework to help them create a more comprehensive and effective portfolio of inclusion strategies.

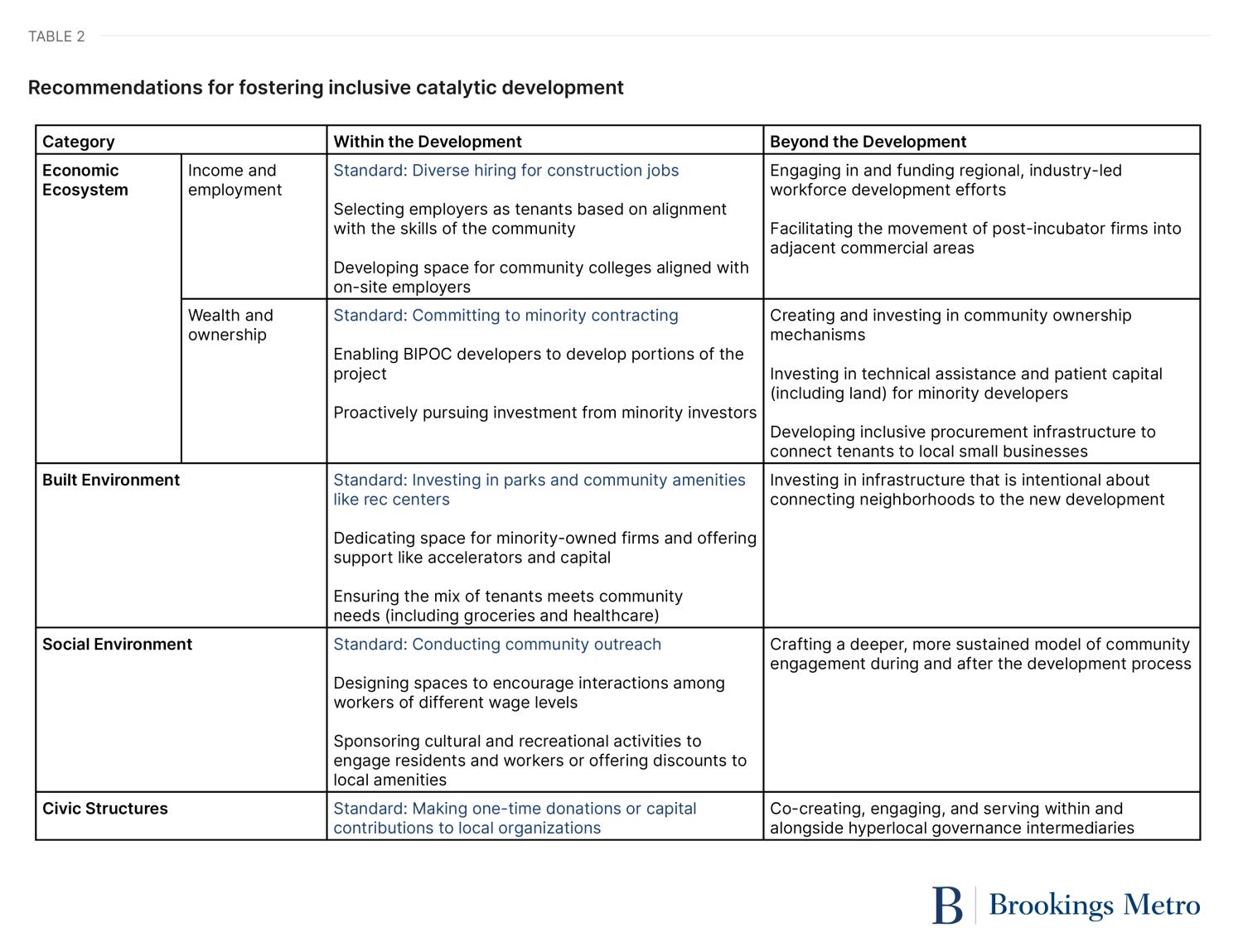

- Motivating more action. For developers who are not investing in inclusion, we hope that this brief makes the concept more tangible and actionable. And by laying out a framework for inclusive development that is more expansive in scope and scale (see Table 2), we also aim to motivate community organizations, city governments, philanthropy, and others to broaden the way they define inclusion when engaging with developers.

- Highlighting what developers can do but also what limitations they face. Such clarity will help governments, nonprofits, and community organizations better understand what they can realistically demand and how they might intervene in ways that help private sector developers undertake more inclusive development.

This framework is not definitive. This is true not only because it is the result of engagement with a handful of developers, not the broader array of public and nonprofit organizations also involved in inclusive development. This is also the case because, even within the real estate industry, developers are only one group of many. Other actors adjacent to developers, such as financiers and brokers, would need to significantly change their practices in order for developers to be able to focus on inclusion more fully and capably. Our hope is that this framework serves as the beginning of a more productive, collaborative discussion among developers and these other public, nonprofit, and private actors.

Why developers? Why catalytic development?

Acknowledging that most real estate developers may still be at the early stages of internalizing the business case for inclusion, we focus on this group in the hopes that doing so will strengthen the understanding of the possible and encourage more actors in this huge and important industry to embed inclusion goals into their projects and practices.

We hope that this report will help make partners and policymakers more effective at demanding, encouraging, and enabling the private sector to develop more inclusive projects.

We focus on catalytic development projects because the business case for investments in inclusion is likely strongest in these projects. Chris Leinberger and Tracy Hadden Loh have defined catalytic development as projects that are large, urban, mixed-use, employer-first, long-term, and backed by patient capital—that is, “equity that has expectations of returns over the long term, generally beyond year five of the investment.”13 Whereas a single residential or office project can potentially succeed in spite of neighborhood- or city-wide economic and social conditions, catalytic projects—due to their size and mix of uses—are far more exposed to such conditions. These mixed-use developments also offer a variety of ways to think about how inclusion can manifest—in terms of housing, the mix of employers, the tenants in commercial spaces, the quality and type of public spaces, and how these elements interact.

There are many opportunities to make suburban development more inclusive and more catalytic, but we focus on projects in urban cores for two reasons. First, we wanted to respond to the demand for new visions for downtowns after the pandemic. Second, these urban projects typically involve a more complex set of competing interests and constraints; models that can account for these considerations while maintaining profitability should translate well to suburban contexts (but the inverse is not necessarily true).

Finally, we focus on developers not just to influence the industry from within, but also to help external actors understand the perspectives, capabilities, and limitations of developers. Most major urban development will continue to be undertaken by firms whose financial commitment to a given project is so short-term that the business case, even if understood intellectually, won’t be strong enough to shape their practices. (To wit: One interviewee said that they had never heard of a developer making a formal, public commitment to inclusion unless mandated to do so by a government.) We hope that this report will help make partners and policymakers more effective at demanding, encouraging, and enabling the private sector to develop more inclusive projects.

Box 1: Developments that informed this report

The core insights in this report come largely, though not exclusively, from developers of the following catalytic development projects.

Aggie Square, Sacramento: This $1.1 billion, 33-acre project is located a few miles from downtown on the Sacramento Campus of the University of California, Davis.14 This project will encompass at least 1.1 million square feet, including research labs; offices for private businesses; student housing; and space for continuing education, workforce development, and community programs.15 City incentives include up to $30 million in tax increment financing for infrastructure upgrades.16 The city, the university, and the project’s developer (Wexford Science and Technology) signed a community benefits agreement (CBA). A CBA is a legal contract between a developer and community organizations that outlines the benefits that the community will receive in return for supporting the developer’s project.

Centennial Yards, Atlanta: This $5 billion, 50-acre project has a target size of 8 million square feet, of which half is expected to be residential.17 The downtown site is adjacent to stadiums and convention facilities on one side and government offices on the other. The proposal is slated to transform an expanse of below-grade parking lots and rail lines formerly called the Gulch. City incentives include capturing 30 years of city and state sales taxes collected within the project footprint and a 20-year break on property taxes, worth up to $1.9 billion.18 The project’s developer, the CIM Group, agreed with the city to goals for minority contracting, construction jobs, and affordable housing.

Michigan Central, Detroit: This development is a 30-acre campus with 1.2 million square feet of commercial real estate centered around the renovated Michigan Central Station (which has been closed since 1988) and the Book Depository.19 Situated a few miles from downtown Detroit, the project, led by the Ford Motor Company, is expected to house 5,000 workers (half of them Ford employees) and provide testing infrastructure for urban transportation innovations.20 The development is subject to the city’s Community Benefits Ordinance, which applies to all projects over $75 million in value.21

Navy Yard, Philadelphia: This $6 billion, 109-acre development, slated to have nearly 9 million square feet of space, is located within a broader 1,200-acre campus about 6 miles from downtown Philadelphia.22 A public-private entity called the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC) acquired the site in 2000.23 Ensemble and Mosaic Development Partners were selected in 2020 to develop the site, in part due to the developer’s commitment to inclusion. Ensemble and Mosaic have made a commitment of $1 billion to diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives (such as hiring, contracting, affordable housing, and investment), which the firm describes as “likely the largest pledge ever in our industry.”24

The Rhodia site, Louisville: The proposed $111 million, nearly 17-acre project is located three miles from downtown and immediately adjacent to a large affordable housing development.25 The long-vacant brownfield site, along with the adjacent housing complex, had once been slated to become a light industrial zone, but this plan failed due to community pushback and insufficient resources. The developer is a minority-owned company, the Re:Land Group, which was formed to pursue this opportunity and then was selected by the Louisville Metro Government in 2020 to develop the site. The Re:Land Group has secured philanthropic funding for a community engagement process and funding from the Louisville Metro Government (via the American Rescue Plan Act) for brownfield cleanup.

Box 2: Defining terms

For some practitioners of economic, workforce, and community development, the terms equity and inclusion are interchangeable. Other practitioners understand equity as something more ambitious and comprehensive. To them, achieving equity means breaking down barriers embedded in current systems to ensure that everyone in a community has access to the same opportunities and outcomes; inclusion, by contrast, means inviting equal participation in the economy without necessarily tackling systemic barriers.

We use the term inclusion in this report because, while equity may be the right goal for a broad coalition of actors working on the regional scale, one developer or one development cannot realistically address the full range of barriers to achieving equity. Still, economic and social inclusion at the place level, which is what developers can most directly influence, is key to creating more equitable conditions in which all people can thrive.

When we refer to inclusion, we primarily (though not exclusively) mean racial inclusion, given the magnitude of racial disparities in cities, the role that land use policies and development practices have historically played in accelerating those disparities, and the powerful evidence that racial inclusion is fundamental to overall economic prosperity.26 We primarily focus on economic inclusion (since for-profit developers are economic actors) but also inclusion in terms of social interactions and civic participation.

It is also important to note that developers use the term equity entirely differently to refer to the cash and cash-equivalents that are the first funds invested into a project and the last to be paid back—the riskiest portion of the capital stack. While we use the term inclusive in this report, the models that we describe can be thought of as an attempt to integrate these two different meanings of equity—that taking social equity seriously in the design and development process can benefit, or at least pose little risk, to investors that have invested financial equity in a project.

Barriers to more inclusive catalytic development

Establishing a new model for inclusive catalytic real estate development requires addressing three core challenges facing not only developers but also the public and nonprofit entities that work to shape and enable inclusive development.

Limited knowledge

The first challenge is that both developers and community organizations possess limited knowledge about how to define inclusive outcomes in the context of real estate development and about how to realize those outcomes most effectively.

They often default to recycling narrow sets of activities that have proven to pass muster in a given city previously.

The need for more inclusive development is easy to articulate in general, but this can obscure the fact that it is highly context-dependent and complex. One version of inclusive catalytic development involves bringing wealth into an economically disadvantaged community without displacing existing residents. Another version involves enabling people of color and low-income individuals to live and do business in a wealthy area that has excluded those groups. Each of these versions demands a very different portfolio of investments, and there is a huge amount of variation within and between them.

This complexity can hamper developer investment in strategies to foster inclusivity. Developers told us that they and their peers do not have a clear definition of the outputs (the bundle of necessary initiatives and investments) or outcomes (the desired changes in the economic circumstances of the community) that constitute progress on inclusion. As such, they often default to recycling narrow sets of activities that have proven to pass muster in a given city previously. For one developer we interviewed, the core elements of the CBA with the city for a project were borrowed directly from another major public development project that took place in a very different neighborhood and time period.

On the one hand, there are numerous resources that define inclusive growth conceptually and that provide examples of ways that real estate development can be more equitable, but developers need more specific knowledge to confidently commit to investments in inclusion within a given project, including more information on the following aspects.

- Quantifying baseline conditions: What is the best way to capture the economic situation of the population that will be impacted by, or could be impacted by, this project? What is the right geography at which to assess impact?

- Defining inclusion: Which disparities are most important to address, given that inclusion can refer to many types of disparities (in terms of employment, income, wealth, or ownership), among many different populations (categorized by race, gender, age, or other factors). What measurable changes would suggest that progress is being made during and after the development process?

- Identifying the portfolio of strategies best suited to respond to these conditions: What set of actions and investments best correspond to the conditions in the identified geography? For instance, some geographies demand more of an emphasis on affordable housing (of varying types), some require a greater emphasis on tenant mix, and some call for more of an emphasis on community ownership.

- Determining what developers can provide, given cost constraints: Relative to the theoretically optimal portfolio of investments for achieving a definition of inclusion, what can a developer commit to offering, in light of the zoning, geographic, cost, and other constraints of a given project?

On the other hand, community organizations, whether acting independently or convened by city government officials, almost certainly have a deeper understanding of the challenges and aspirations of their neighborhoods than developers do. But community organizations also face knowledge gaps that may inhibit their ability to effectively shape development projects. Exerting effective influence requires not just understanding the needs of the community but also possessing the ability to strategically align those needs with the capabilities of developers. This raises several challenges.

- Calibrating demands with developer capabilities: Because the capabilities of developers are largely unknown to nondevelopers, community organizations sometimes demand too much of developers in certain areas in which developers are highly constrained, while not focusing at all on other areas in which developers are more able and willing to act. For example, a community coalition might make unrealistic demands in terms of affordable housing in a development (and expend significant resources and political capital trying to make marginal improvements in this area), while not exerting any pressure regarding the mix of employers on site, which a developer may have much more latitude to shape. This is a suboptimal outcome for developers, in that it slows down the development process, and for communities, which receive a smaller overall package of benefits than they otherwise would (because their demands are not well calibrated and because the delays in the development process are costly to the developer and render them less able to deliver on community demands).

- Identifying the right models: Even if the needs of communities and the capabilities of developers are understood, public and nonprofit organizations that serve as intermediaries may not be aware of proven or emerging models that most effectively address community needs. It is one thing to know that inclusive workforce development is at the nexus of communities’ needs and developers’ capabilities; it is another matter to know which workforce development practices are most likely to achieve specific outcomes. The risk is that communities will make the right demand generally, only for it to manifest as an ineffective program or investment.

- Acting in coordination at the neighborhood scale: Ideally, community organizations would be able to set an agenda for how investments writ large should meet community needs, which discrete development projects could then separately address. (For example, perhaps one development could appropriately incorporate a grocery store and another nearby development could include affordable housing). But these community organizations typically have little insight into the broader development landscape such that their only opportunity for shaping development is through reactive, one-off negotiations focused on a single project. This means that they may use all their influence to secure a certain amenity at one development not knowing that they could have more easily obtained that amenity via another nearby, upcoming development. Or, absent a coordinated means for defining and engaging on inclusive development, multiple community organizations may all demand the same type of amenity from different proximate developments and fail to demand other needed amenities at all.

Community organizations sometimes demand too much of developers in certain areas in which developers are highly constrained, while not focusing at all on other areas in which developers are more able and willing to act.

Box 3: Defining community “demands”

When we refer to community organizations making “demands” of developers, we do not necessarily mean demands made through formal negotiations on a CBA. Demands from community organizations could take a variety of other forms, like the creation of a new city government policy informed by members of the community, an inclusive development framework adopted by a community organization to shape future development, or a long-term partnership between a community organization and a developer.

One of our goals with this report is to advance a framework for inclusive development that makes CBA negotiations less necessary, as CBAs are expensive and time-consuming for community organizations and developers alike (and therefore are not a realistic means of influence for many under-resourced communities). Our hope is that, with this framework, developers and community organizations will be able to more quickly reach a shared definition of both what is desirable and what is possible, in part because city agencies and other actors will be able to establish clearer city-wide expectations and policies that inform and frame these negotiations. (Moreover, as we later explain, we hope that community ownership of real estate becomes more widespread, in which case community members, organizations, and developers would be on the same side rather than working in opposition.)

When we refer to the demands being made of developers in this report, we often describe city government officials and community organizations as one bloc. We recognize that the development preferences of city governments are not always in line with those of community organizations (though exploring those tensions and power dynamics is beyond the scope of this report). However, when developers face pressure to make their projects more inclusive, it is usually stemming from some formal or informal combination of community organizations and city government officials, so from a developer’s point of view they may fairly be understood as one bloc. For example, CBAs are technically legal agreements between community organizations and a developer (and legal scholars argue that the legality of CBAs could be questionable if city governments extort developers by formally requiring CBAs).27 But community organizations often only have leverage to demand CBAs because they know that a city policymaker or regulatory body will disapprove of, delay, or withhold funding from a project if the developer does not agree to a CBA.

Limited motivation

The second challenge is that developers, and sometimes community organizations, have limited motivation to pursue inclusive development as we have defined it.

Most obviously, many developers have limited internal motivation to invest in inclusion efforts because the business case is not clear given their short-term financial commitment to their projects. While this may not be true for long-term catalytic development projects (over 15 to 20 years), inclusion efforts are unlikely to meaningfully or measurably affect profitability in the time frame of more typical developments. As such, most developers are only motivated to invest in inclusion to the extent that it reduces delays or overcomes barriers during the entitlement and permitting process.

Even for long-term investments, there remains a key question: to what degree does a more prosperous community improve profitability? A report published by the Urban Land Institute called 10 Principles for Embedding Racial Equity in Real Estate Development acknowledges this: “Although the benefits of racial equity can be difficult to model financially . . . and typically upfront costs and long-term benefits can be hard to capture, the benefits are nevertheless real and important to recognize.”28

Critics have claimed that CBAs are often redundant with existing policies and poorly enforced, meaning that they may often have limited power to motivate developers to act differently.

Most developers also lack external motivation to a degree that may not be recognized, given how often community organizations and governments seem to directly intervene in major development projects. Examples include CBAs that have shaped catalytic developments (such as the Staples Center in Los Angeles or Atlantic Yards in Brooklyn) or the agreements that are made in return for public incentives or zoning variances (such as Amazon’s HQ2 project in Northern Virginia). Despite these high-profile examples, CBAs remain relatively rare, and their demands typically do not include many of the components in our framework. In addition, critics have claimed that CBAs are often redundant with existing policies and poorly enforced, meaning that they may often have limited power to motivate developers to act differently.29 Further, while high-growth cities may be able to make demands of developers, this is harder to do in low-growth cities that are desperate for any investment via development, whether inclusive or not.

There tend to be two distinct—though certainly not monolithic—types of community organizations that aim to shape development. The first type is generally comprised of wealthy white homeowners that expressly aim to inhibit development generally and perhaps inclusive development—affordable housing, for example—in particular. Addressing this NIMBY opposition requires a number of process and policy changes that are beyond the scope of this report.30 The second set of actors includes community groups led by people of color in disinvested areas—including areas harmed by prior, ostensible, urban renewal efforts; these groups are highly motivated to push for inclusive development and are often party to CBAs with developers.

The groups of people and organizations that have the time and inclination to make their voices heard are likely to be over-representative of existing residents immediately adjacent to the project. This can result in a tendency to over-emphasize neighborhood preservation rather than adding new assets or amenities.

Even these latter organizations still may have a lack of motivation to pursue inclusive development at a geographic scale commensurate with the potential impact of the development, or in a way that considers all members of the community or potential future community residents. The groups of people and organizations that have the time and inclination to make their voices heard are likely to be over-representative of existing residents immediately adjacent to the project. This can result in a tendency to over-emphasize neighborhood preservation rather than adding new assets or amenities. This in turn can manifest as a focus on limiting construction-related disruption, limiting traffic related to large employers, or limiting new housing development to preserve property values. A different conception of what constitutes inclusive development—which in our view includes creating high-quality employment and wealth-creation opportunities for people who may not currently (or ever) live in the neighborhood—may encourage cities, nonprofits, and other actors to rethink community engagement processes.

Limited capabilities

Even large, for-profit developers may have a limited ability to deviate from profit-maximizing approaches to urban development.

One key factor is that urban land values have increased substantially. One major reason for this is the limited supply of pedestrian-friendly land in major urban areas. According to analysis by Michael Rodriguez and Chris Leinberger, only 1.2 percent of urban land in the 35 largest metro areas in the United States is “walkable urban,” (and only 0.2 percent is walkable urban land that serves a “regionally significant” economic function).31 This in part reflects resistance to upzoning or densifying other parts of cities, despite the clear demand for more walkable urban places—as reflected in an approximately 50-percent price premium that Rodriguez and Leinberger found for offices and multifamily properties in these areas. The result is that land costs in walkable urban places are under tremendous upward price pressure (notwithstanding post-pandemic declines in the price premium relative to suburban areas). Whereas a rule of thumb for developers used to be that land values should be no more than 20 percent of the capitalized value of what would be developed on that land, in some market contexts, it has been the reality for decades that land values at times exceed 40 percent of the value of the proposed development.32

Recently, this long-term trend of increasing urban land costs has been coupled with high interest rates that are significantly slowing urban development, even in cities like Seattle that had experienced sustained booms in development before the pandemic.33 Combined, these factors substantially limit the feasibility or profitability of urban development and, therefore, the latitude or willingness of developers to take creative, long-term approaches to investing in inclusion.

Smaller, more mission-driven developers are even more constrained—despite their potential willingness to take lower profits in return for mission-related outcomes—given the barriers and biases they have to contend with to secure capital. These barriers are especially pronounced for developers of color, as discussed later in this report.

An emerging framework for inclusive, catalytic development

Community groups and developers should be on the same side of the table as partners who both want the communities they are involved in to be improved over the long term.

More inclusive catalytic development will require a paradigm shift created by new actions from both developers and community organizations—ideally in a more coordinated and collaborative manner than is typical today. Community groups and developers should be on the same side of the table as partners who both want the communities they are involved in to be improved over the long term.

To define the key elements and ideal outcomes that should guide their work, we use the Transformative Placemaking Framework developed by the Brookings Institution’s Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking. It offers a holistic approach to creating more connected, vibrant, and inclusive communities. Transformative placemaking is defined by three distinct qualities.

- Scope: Transformative placemaking is more expansive than traditional placemaking in that it strives to create destinations for work, commerce, recreation, and residential life that generate economic value for the broader city and region.

- Scale: Transformative placemaking demands a geographic scale larger than a single building, block, or public space. It instead centers on specific subareas of cities or regions where economic and/or infrastructure assets cluster and connect—but where the reach and impact of those assets are limited by varying place-based challenges.

- Integration: Transformative placemaking requires an integrated approach that breaks down the siloes between economic development, community development, and land use and infrastructure planning. The goal is to create places that are economically dynamic, locally empowering, and connected; to ensure that the built environment is accessible and sustainable, and to foster communities that are socially and culturally vibrant and inclusive. These outcomes support and are supported by robust civic structures that are locally organized, inclusive, and supportive of network building.

We use this framework to broaden the definition of inclusive development such that it encapsulates more than stand-alone efforts around minority contracting or small-scale and/or single-purpose projects like affordable housing. As stated in a 2019 report by the Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking, “When implemented in tandem, [such] efforts—from nurturing local talent, to creating mixed-use physical spaces, to promoting social interaction, to strengthening community networks—can have the most impactful outcomes.”34

Emerging practices

Captured here is a non-exhaustive set of recommendations and example practices informed by the activities, commitments, and plans of the handful of developers that we interviewed; this curated list also includes strategies and programs that they cited as inspiration. A for-profit developer is either already doing or seriously considering nearly every activity mentioned here, so other developers—and the public and community groups that invest in or are impacted by projects—can trust that each is conceivably doable (while recognizing that different projects have significantly different constraints).

Economic ecosystem. Inclusive catalytic development helps to nurture a connected, locally empowering economic ecosystem that creates employment opportunities and supports ownership and wealth building.

Catalytic development, by definition, generates permanent employment opportunities. To this end, inclusive catalytic development should strive to select tenants that provide abundant, quality jobs. Developers could work with economic and workforce development organizations to define a quality job assess which industries or occupation groups have an abundance of those jobs; and best match the skills, experience, and aspirations of residents of a given community. One interviewee noted that developers have some latitude to shape their employer mix but lack insight into a community’s capabilities and needs.

Aside from helping to create jobs, developers can consider creating space in developments for workforce development entities, community colleges, and vocational training providers that can connect community members to these employment opportunities. One developer explained that not only are community colleges valuable tenants in their own right but that they also help attract institutions and businesses that value proximity to workforce pipelines. For example, situated within Aggie Square’s nearly 700,000 square feet of lab and innovation space will be a 250,000- square-foot Center for Lifelong Learning that will serve as the front door to UC Davis’ Continuing and Professional Education office as well as a network of other workforce development organizations.35 Relatedly, the Aggie Square CBA stipulates that Wexford Science and Technology will identify a nonprofit organization that will hold regular events to discuss the skill requirements for jobs within the development, provide opportunities to meet hiring managers, and offer information about skill development opportunities.

While this framework argues that inclusive catalytic development requires developers to consider the employment impacts of their decisions beyond the construction phase, they can also do more to promote inclusion within the construction workforce. Public and nonprofit partners cannot build inclusive talent pipelines on a meaningful scale if developers only engage with those partners when a project demands that the developer or contractor hit diverse hiring targets—as one interviewee said was commonly the case. Rather, developers should be a more active and sustained presence in regional workforce development initiatives, helping providers shape construction programs so that they better and more consistently train workers to meet developer needs.

One recent example is Hire360 in Chicago. Co-founded in 2019 by the development firm Related along with other developers, contractors, labor unions, and the United Way of Metro Chicago, the group provides a range of services and case management to connect underrepresented individuals to apprenticeship opportunities in the building trades. As of early 2023, Hire360 reported that it had supported 200 apprentices.36 A new Training and Business Development Center is set to open in the South Loop neighborhood soon, funded by $3.5 million in state and federal funds plus future investment of equal magnitude from private and philanthropic funders. However, as several interviewees noted, efforts to market the trades and connect people of color to pre-apprenticeship programs will not amount to much if openings for apprenticeship programs remain limited (as they are for many occupations) and if unions do not make significant strides in terms of diversity and inclusion.37

Beyond creating accessible job opportunities, inclusive catalytic developers can also help build wealth and support ownership as part of their projects.

When the community has an ownership stake, the fiduciary responsibility of the developer to investors creates a new level of engagement that is of real value to the community.

For example, several developers we interviewed were committed to providing opportunities to minority-owned firms to develop or build portions of the project. This typically requires breaking projects into smaller parcels and potentially putting up bonds for firms that don’t have the capital and track record to secure financing. They can also proactively recruit investors that might not otherwise engage in large-scale projects. Ensemble and Mosaic Development Partners, co-developers of the Navy Yard, set a goal of securing 20 percent of the equity for its projects from minority investors.38

Inclusive development ideally also involves intentional efforts to build wealth and opportunities beyond the footprint of the development itself. One mechanism for doing so is creating neighborhood investment funds to allow community members to acquire an ownership stake in the development or in surrounding properties for a relatively small investment. Beyond the funds themselves, developers could commit resources for implementation, including technology systems, the long-term involvement of finance and technical assistance providers, and community engagement. One developer cited the Nico Echo Park “neighborhood REIT [real estate investment trust]” in Los Angeles as inspiration, and numerous other models exist around the country.39 The potential impact here should not be conceptualized just in terms of the potential financial dividends or returns that community investors could accrue. In addition, when the community has an ownership stake, the fiduciary responsibility of the developer to investors creates a new level of engagement that is of real value to the community.

Another mechanism for helping a development foster community wealth is creating inclusive procurement infrastructure to be shared by tenants, so that they are more likely to buy supplies and services from small and minority-owned local firms. These investments in matchmaking could be paired with developer investments in programs that provide consulting and capital to these minority-owned firms. This amounts to developers encouraging and enabling tenants to organize as an anchor collaborative rather than relying on third-party entities to do so.

A final way for developers to grow wealth in a community is to invest in programs that help grow the pool of minority developers. This could involve investments in the talents of professionals who aspire to work for large development firms, which are overwhelmingly white, or investments in emerging entrepreneurs that want to establish and grow their own firms. For example, the Centennial Yards Company participated in Project REAP (the Real Estate Associate Program), a national initiative to prepare college graduates of color for leadership positions in large commercial real estate development firms. Project Destined is another that focuses on college students. It provides training to about 2,000 students from 350 colleges annually, and it offers paid internships through partnerships with 250 firms.40 A complement to this college-oriented approach is to focus on building the capabilities and networks of early-career real estate developers. A mature model in this space is the Associates in Commercial Real Estate program in Milwaukee, a partnership between the Local Initiatives Support Corporation, Marquette University, the Milwaukee School of Engineering, and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee with major philanthropic and technical support from the local real estate community.41 Recently, Capital Impact’s Equitable Development Initiative has trained nearly 200 minority developers of color in three metropolitan areas since 2018.42 Yet another approach is to develop the skills of potential real estate developers in neighborhoods. Established initiatives include Building Community Value in Detroit and Community Desk Chicago; more nascent examples include Buffalo’s Community-Based Real Estate Development Training program and Seattle’s Build ArtSpace Equitably initiative.

Built environment. Inclusive catalytic development supports a built environment that is flexible, accessible, and resilient. Beyond creating employment and ownership opportunities, developments—both the buildings and surrounding areas—can also be designed to advance racial and economic inclusion in the surrounding community.

Simply including public space or building a trail is not enough to achieve an equitable outcome: these spaces can either address disparities or make them even worse.

On the housing side, many local governments rely on either inclusionary zoning or affordable housing proffers as an integration strategy to deliver economically diverse residential communities. Reserving some new housing units for lower-income households is a relatively simple and familiar process for many residential developers and is also supported by multiple federal tax credits, loan products, and programs. However, the paradox of affordable housing construction is that to advance inclusion (as opposed to concentrating poverty), units must be built in wealthier neighborhoods where land costs are higher. In many cases, catalytic developments in higher-cost areas have converted land contributions from either the public sector or mission-aligned, community-based organizations or institutions that own land into affordable housing to achieve inclusion goals.

A major emphasis of several developers we interviewed was creating space and offering support for minority-owned businesses within the development. For the Navy Yard development in Philadelphia, this meant not only setting aside 25 percent of retail space for minority- and women-owned businesses but also committing resources to help these capital-deprived businesses succeed, whether in the form of upfront money to fit out their space or a six-month ramp-up period with little to no rent.43 Detroit’s Michigan Central development includes underrepresented founders in its incubator and accelerator spaces, as well as an ecosystem of support including capital provision, peer mentoring, and business development. The Cincinnati Center City Development Corporation (3CDC) has worked to increase diversity among tenants using a tiered lease structure for restaurant and bar tenants, which charges the higher of two options: a low rent per square foot or a percentage of gross sales. This model allows new tenants to pay low rent while establishing their business and later allows 3CDC to share profits with successful businesses. There is a business case for such investments: mixed-use projects perform better with locally curated retail that creates a more distinct place and makes retail shopping an experience.

It is also important to ensure that the mix of retail- and service-sector tenants meet the needs of the community. One developer described intentionally bringing a bank, a healthcare facility, and a grocery store into a mixed-income development in response to the community’s reliance on check-cashing services, disparate health outcomes, and lack of access to fresh food. The developer went further, demanding (though not technically mandating) that the grocery store company find a diverse owner for this franchise. Working with the developer, the firm ultimately selected a 28-year-old Black man who had grown up in the neighborhood to be the owner. The developer described the opening of the grocery store as hugely meaningful for the community. Developers could be more systematic about identifying community needs and pressing potential tenants to seek out diverse owners or leaders.

A separate research project from the Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking investigated promising practices for planning, programming, and governing public spaces, often as part of catalytic redevelopment projects, as a way to advance inclusion.44 Simply including public space or building a trail is not enough to achieve an equitable outcome: these spaces can either address disparities or make them even worse. Asking and answering explicit questions about who public spaces are designed for; drawing big boundaries; and including direct connections to broader communities in implementation requires resources, capacity, and effort. When the public sector contributes land or gives enhanced entitlements to a project, public spaces are often part of the deal. However, these transactions rarely come with a long-term monitoring or management commitment or plan for inclusive outcomes. Structuring governance for the long term can change that.

Social environment. Inclusive catalytic developments are socially and culturally vibrant and inclusive. Inclusive development is about outcomes, not just processes. Still, well-designed, sustained, community engagement processes are likely to yield developments that produce better and broader results.

Tarik Nally described how the Re:Land Group, the developer in Louisville, did not want to replicate what members of the community (and most communities) typically experience, which he described as the “town hall version of community engagement—there’s a one-hour presentation, there’s big white sheets of paper and sticky notes, people answer questions about what they want to see out of their neighborhood, and then they leave.” In contrast, the Re:Land Group organized a cohort of 40 people that were representative of the community and hired a facilitator to guide them through a process of first “understanding the language of land use, understanding holistic economic development principles, learning about placekeeping, and finding power in their voices” before debating what the Rhodia development should look like.45 The cohesive, longitudinal nature of the cohort process allowed for relationship building and healthy debate that otherwise wouldn’t have occurred. Nally also emphasized that it was important for the Re:Land Group not to lead this process: the firm felt that otherwise community members would tell the Re:Land Group what they thought firm representatives wanted to hear, since the site had been vacant for 20 years and since community members may have been nervous about being too ambitious in their vision. This work, funded by more than $800,000 in grants from local foundations, is decidedly different from the more sporadic and superficial community development processes in which developers often engage.

Beyond the engagement process itself, developers should also look for opportunities to incorporate outdoor and indoor areas that the community can use as gathering and social spaces. In the Aggie Square development, Wexford Science and Technology agreed in its CBA with the city that it would provide $1 million annually in discounts and fee waivers for community use of the Innovation Hall meeting space.46 One way to achieve the creation of inclusive spaces is by treating community members as citizen experts and respecting their insights into how people actually experience space and place, which cuts against current tendencies to prioritize iconic design.

Civic structures. Inclusive catalytic developments often both support and are supported by hyperlocal entities to help with place governance.

Investing in an intermediary to help aggregate and amplify a community’s voice is not only better for the community but also better for the developer because it minimizes the need to navigate the often-conflicting demands of various neighborhood groups.

Community engagement, even when done well, is typically conceived of as something that happens during the design and construction phases of a project. But developments change over time, as do the circumstances and needs of a community. To ensure that developments live up to their promise and continue to produce economic and social inclusion over time, some developers are investing in permanent intermediaries as long-term partners to help facilitate place governance and shape developments as they evolve. Such structures can also provide a broader avenue through which communities can share ideas, voice concerns, advocate for coordinated investments, and co-design community improvement strategies.

For example, in Aggie Square, the developer Wexford Science and Technology is responsible for convening an Aggie Square Community Partnership to oversee a permanent community fund (see more below). Wexford has made similar investments in Baltimore, where the firm is a supporter and member of the Southwest Partnership, a coalition of multiple institutions and neighborhood groups in the area surrounding the University of Maryland BioPark (of which Wexford is a major developer). One developer noted that investing in an intermediary to help aggregate and amplify a community’s voice is not only better for the community but also better for the developer because it minimizes the need to navigate the often-conflicting demands of various neighborhood groups.

These place governance entities are distinct from business improvement districts (BIDs). The latter are usually funded by an additional tax on properties within a defined area, and the state enabling legislation typically requires that the governing boards of BID entities be composed of the property owners who are paying the taxes. In contrast, the more expansive place governance described here includes not just property owners but other hyperlocal interests such as property tenants, residents, and nonprofit (and thus untaxed) institutions. Sourcing the operational funding for such entities could be done by building on the BID model, or more commonly through a nonprofit model such as the South Lake Union Community Council in Seattle, which is supported by contributions from property owners, employers, and major donors.47

Enabling and scaling inclusive catalytic development

As described above, forward-looking developers are undertaking a range of activities to make their projects more racially and economically inclusive. But what is enabling these developers to do things differently than most? And what can other actors in the development ecosystem do to encourage and support them?

Enabling inclusive catalytic development

From our interviews, we identified three consistent, if not universal, enabling practices that undergird developers’ efforts to produce more inclusive projects. If more developers adopted these practices, it would lead not only to more widespread implementation of the kinds of strategies described above but also more widespread experimentation that would yield new and innovative ideas and approaches.

Developing a clear—and firmly enforced—vision for inclusion. None of the developers we interviewed had defined inclusion comprehensively—that is, as a concrete portfolio of actions with a measurable set of outputs and outcomes they were expected to yield in a surrounding community. But most did have a clear vision for the impact they intended to have that extended beyond the formal requirements of a CBA—and even beyond the footprint of the development itself. Often this vision motivated the firm’s work overall, not just in relation to a single project.

Take, for example, the Re:Land Group in Louisville. The guiding question for its envisioned 18-acre mixed use project was “what does a community deserve”? The firm described its design approach as beginning with “intentionally thinking about the actual human beings whose lives will be facilitated by the space they live in: What does a grandmother get, what does a child get, how much different can their lives be because we used space in a powerful way?” This question led to an unusually broad understanding of the components of an inclusive project: preschool offerings, community schools, senior housing, job training programs, on-site employers providing relevant jobs, community-oriented healthcare, and healthy buildings.

Several other developers had a guiding vision that focused on striking the right balance between catalyzing new development while not displacing existing residents. One developer called this “gentrigration” (combining gentrification and integration), noting that it was just as important to not concentrate wealth as it was to not concentrate poverty. Similarly, another developer’s stated focus was “limiting harmful gentrification.”

Shifting from an expectation that partners would make ostensibly their best efforts to treating inclusion requirements as real mandates.

While not our interviewees, Jodie McLean, the CEO of the developer EDENS, and Richard Florida described in Harvard Business Review their vision for the 45-acre Union Market district in Northeast Washington, DC, a vision that resonates with the above themes and the Transformative Placemaking Framework.48 They described their efforts as “reimagining the project as an economic ecosystem rather than a collection of brick-and-mortar buildings . . . transforming a former food production and distribution center into a district for inclusive prosperity . . . that would need to create jobs, engage the surrounding community, inspire connection between the existing neighborhood and the broader city, preserve historical identity, and incubate entrepreneurship—all while making economic sense as a development.” Importantly, they also wrote that this vision needed to be made concrete in the form of “new, non-traditional metrics . . . to track the project’s community impacts while making sure that investors and capital partners were still accomplishing their financial objectives.”

Any vision, no matter how compelling, will fail to translate into reality unless it is firmly enforced by developers. One developer emphasized the importance of shifting from an expectation that partners would make ostensibly their best efforts to treating inclusion requirements as real mandates. In addition to hiring a diverse range of engineers and architects, the developer said, “we made it a requirement, not an option, for our professional service providers to partner with diverse firms so that they could grow and be able to add this project into their portfolio so that they could better market themselves for larger projects in the future. It was a mandate—you can’t say, ‘I’ll try my best.’ You won’t get this job. You will not be on our team if you’re not committed to our initiatives.”

Box 4: Why aren’t developers measuring inclusion? How would they do so?

A growing number of economic development organizations, research organizations, and places are creating metrics dashboards to define and track inclusive growth at the regional level. In almost all cases, developers are at best relying on conceptual definitions of inclusion that are not concrete or measurable, ones that, therefore, don’t allow them to track progress, shift strategy, and help other developers. A few factors can likely explain the lack of a consistent, quantitative theory for how to define the intended outcomes of a real estate development.

One factor is that economic data are very scarce at the neighborhood (or even subregional) level and often lack racial detail, are published irregularly, or have large margins of error. As a result, developers cannot simply adopt regional frameworks and localize them.

Another factor is that neighborhoods are extremely varied in their economic and social conditions. This is why inclusive development can mean bringing wealth into disinvested neighborhoods without causing displacement or it can mean bringing affordable housing and accessible jobs into wealthy neighborhoods, two sets of circumstances that would demand a different approach to defining and measuring outcomes. Whereas many regional economic development organizations around the country are converging on a roughly similar way of defining inclusive growth, that is less likely to happen among developers because neighborhood-to-neighborhood variation is greater than region-to-region variation.

Lastly, typically the population within a neighborhood changes more than the population within a region, making it harder to measure inclusive growth—improvements in certain indicators could be the result of new residents moving in rather than existing residents experiencing economic mobility.

Despite these fundamental challenges, there are resources to help developers and community partners identify and track meaningful measures of economic inclusion in the neighborhoods in which they work. Developers should be aware that many frameworks for inclusive growth metrics are designed for a regional scale and that the same data are likely not available, or meaningful, on a neighborhood scale. A useful starting point may be the Brookings Metro report Reducing Poverty Without Community Displacement: Indicators of Inclusive Prosperity in U.S. Neighborhoods, which identifies eight internal indicators (related to conditions in a particular neighborhood) that are associated with neighborhoods that experienced “a large decrease in their poverty rates” without displacement between 2000 and 2015.49 Even with these analytical tools in hand, developers need to be prepared to engage in complex discussions about what constitutes progress on equity or inclusion. These terms have many dimensions—racial, economic, and gender-based—that can sometimes be in tension, and the right set of metrics may vary from neighborhood to neighborhood.

The public sector and research institutions can help support the advancement of inclusive catalytic development by leading on the collective challenge of developing, hosting, and maintaining better neighborhood-level metrics. For example, in 2023, Philadelphia created ProgressPHL, a social progress index that measures aspects of social and environmental well-being.50 This index has now been adopted by Shift Capital, a certified B-corporation real estate developer working in Philadelphia and several other East Coast markets.51

Building teams with broader skillsets. Inclusive catalytic development involves investments in a variety of domains—such as affordable housing, entrepreneurial support, workforce development, and community ownership of real estate—that each require collaboration with external entities with expertise and connections to implement programs. Building and sustaining collaboration with a range of organizations including community colleges and business accelerators is challenging if staff within the development firm do not understand those systems deeply.

Economic development insights can help developers broaden their understanding of success.

Several developers we interviewed emphasized the importance of having an internal team that had expertise in all of the domains relevant to their inclusion portfolio, a form of vertical integration characteristic of catalytic developers as defined by Leinberger and Loh, so that they could effectively engage external partners and develop pilot projects around new concepts.52 One developer had professionals on staff with expertise in workforce development, placemaking and inclusive design, startup support, and so forth. Another said that economic development insights can help developers broaden their understanding of success: “Every developer needs an economic development team member because otherwise they really don’t know how to maximize the return on their investment. They look at deals as singular projects, but how the deal fares is impacted by what’s happening outside of that one deal.” She further noted, “developers that actively pursue place-based investment strategies—whether in a neighborhood or over several square miles—will see far better returns.”

Creating ongoing funding sources for inclusion. A developer’s theoretically long-term commitment to inclusion is unlikely to actually translate to sustained and responsive involvement if the developer’s financial commitment is entirely front-loaded. Two developers that we interviewed created and capitalized funds for inclusion efforts that are continually replenished through annual contributions that are indexed to income generated by the development.

In the case of the Navy Yard in Philadelphia, the developers made an initial contribution of $1 million and committed to subsequent contributions of 2 percent of net operating income annually.53 This TNY Empowerment Foundation will be overseen by a board of directors comprised of representatives from the two developers leading the project, the city agency that owned the land, and city council members. It is intended to be used to fund workforce development initiatives, a revolving loan fund for minority contractors to assist with payroll and upfront material purchases, working capital for minority business owners operating within the development, and so forth. In Sacramento, Wexford committed to an upfront contribution of $150,000 and then further contributions from an assessment of $0.015 per rentable square foot, or approximately $150,000 annually upon full occupancy.54 While this fund is smaller, it is also more community-led. It is governed by a community partnership comprised of the developer and major anchor tenants, as well as an equal number of neighborhood partners (as chosen by residents and business owners in the community).

Scaling inclusive catalytic development

Public sector officials, nonprofit leaders, residents, and even the media often assume developers have more power and/or adeptness than they do to address deeply rooted economic inequities in and around urban cores.

Many of the specific strategies described above are promising but untested or else they are proven but small in scale. This is in part due to capacity gaps that seriously constrain the ability of developers to invest in inclusion, especially as walkable urban land has become far more expensive and as post-pandemic interest rates have risen. Public sector officials, nonprofit leaders, residents, and even the media often assume developers have more power and/or adeptness than they do to address deeply rooted economic inequities in and around urban cores. Developers alone cannot be counted on to address such challenges—even if they are motivated by the business case and even if they are pushed by community organizations that have their own comprehensive inclusion agenda.

This means that other actors will need to step in to provide structures, mechanisms, and capital that help developers do things differently and at greater scale. While a full exploration of the role of other types of entities—such as city governments, philanthropic foundations, and financial institutions—is beyond the scope of this report, our interviews surfaced several ways in which these actors could better shape how for-profit developers act.

Public development authorities can play a bigger role in urban real estate development. Public and quasi-public development authorities are one way for government entities to shape how private developers operate more directly than current tools allow and to use publicly owned land in far more productive ways than governments typically do. By one estimate, the public portfolio of real estate for the typical city is equal in value to the city’s gross domestic product and represents 25 percent of the total value of all real estate within that city.55 Many city governments, however, do not know the extent or value of their own real estate holdings and are not using them effectively to maximize tax revenue or as the foundation of inclusive catalytic development projects.

Perhaps the most prominent example of a public development authority in the United States is the PIDC, which has settled over 13,000 transactions and deployed more than $19 billion in financing for development projects and small businesses since 1958.56 The PIDC acquired the Navy Yard property in 2000, and in 2020—having formally prioritized racial diversity as a key criterion—selected Mosaic Development Partners, a Black-owned firm, as a co-developer (with Ensemble) for a nearly $6 billion, 20-year project to create a mixed-use development.57

Another, newer model is Seattle’s Cultural Space Agency, formed in 2020. Randy Engstrom, a former director of the city’s Office of Arts and Culture, describes this public authority—the first the city had chartered in about 40 years—as a “mission driven and real estate intermediary that could stand in between community and market forces.”58 In its first year, the agency developed, or was in the process of developing, several large projects, including affordable housing developments with ground-floor condo units for creative uses. The value of the public development authority model, according to Engstrom, is that it can accept property from the city, accept philanthropic grants, and bond against future revenue. In 2023, Seattle voters approved the creation of the Seattle Social Housing Developer, another public development authority.

These models likely need to be expanded, strengthened, and designed in ways that allow them to spur inclusive catalytic development.

City governments can do more to proactively define inclusive development. While city governments often have a desire to ensure that development yields more inclusive outcomes, that desire manifests as an array of tools that only deal with parts of the inclusive catalytic development framework and often only do so indirectly. Most city tools relate to affordable housing, often in the form of linkage fees (which don’t actually shape the development itself but secure funding for housing elsewhere). Cities can sometimes effectively require developers to enter into CBAs as a quid pro quo for zoning variances or public funding, but usually the final agreement is between the developer and community groups, since legally city (or state) governments are limited in terms of what or how much they can demand from developers.59 As such, the bundle of CBAs that may exist in a city at a given time does not necessarily add up to a cohesive reflection of public sector priorities.

I do not believe developers, by and large, have moved past process because process is easy. It is what is expected by cities and counties and neighborhoods who themselves don’t know how to measure impact. And so instead, they measure process.

In fact, most cities do not have a clear, overarching statement about what constitutes inclusive development. At most, a city might clearly stipulate when CBAs will be required (as in Detroit’s Community Benefits Ordinance), or a city might define goals for minority participation in the construction process (as in Atlanta’s Equal Business Opportunity Program). This contributes to uncertainty for both developers and community organizations, leaving neither side with an objective and reasonable starting point for negotiations. As one interviewee put it, “I do not believe developers, by and large, have moved past process because process is easy. It is what is expected by cities and counties and neighborhoods who themselves don’t know how to measure impact. And so instead, they measure process.”

City governments could be more proactive about working with an array of community organizations and other nonprofits to define an inclusive development framework for their cities overall, both in terms of the array of strategies that are most relevant to a given city’s needs and the indicators that best capture whether progress is being made on key outcomes. City governments could also invest more in research to help developers and communities understand baseline economic and social conditions in neighborhoods. While these frameworks would be nonbinding (unless they were somehow woven into other policies), public sector leadership can help shape perimeters and set expectations.

Opportunity funds can channel investment to prioritized corridors. While linkage fees and CBA-mandated payments into affordable housing funds are common ways that developers invest in inclusion, there are few analogous models that require or enable developers to pay into funds for other uses relevant to economic opportunity.

Critics often note that linkage fees for affordable housing can contribute to concentrating poverty by enabling developments in wealthy neighborhoods to pay for affordable housing construction in low-income neighborhoods rather than creating mixed-income projects. But that critique may not be as strong when it comes to investment in assets other than housing. Rather than asking a developer to create space for BIPOC-owned small businesses on the site of a downtown development, for example, it may have an equal or greater impact if the developer pays into a fund that deploys capital into prioritized commercial corridors in underserved communities of color.

Chicago’s Neighborhood Opportunity Fund is one such model.60 Developers that want to exceed zoning limits in downtown Chicago can pay a portion of a development’s value into the fund, and then the city disburses those funds into commercial corridors in Chicago’s South and West Sides. The fund has two programs: a small grant program awarding up to $250,000 and a large grant program awarding up to $2.5 million.61 Eligible expenses include land acquisition, building acquisition, architecture and engineering fees, façade improvements, and so forth. Projects are evaluated according to specific criteria, including readiness, feasibility, and catalytic impact—which is defined in part as providing goods or services that an area lacks.

Such models address, at least in part, a few key problems with CBAs and similar models used to achieve inclusive development. One is that those processes tend to revolve around what happens on the site of a given development or in its immediate neighborhood, even if the development could have a bigger impact for the community in a geography that’s not immediately adjacent to the project itself. It may be the case that, say, $1 million of developer investment is far more impactful if it is (hypothetically) used to help establish five thriving BIPOC-owned businesses in a disinvested commercial corridor, versus creating space for two such businesses in a downtown project. Such a model also solves a second problem, which is that CBA processes are extremely demanding for community organizations. Through a mechanism like the Neighborhood Opportunity Fund, community organizations can engage one time with a city agency to identify prioritized corridors and document needed goods and services, and then the city can do the work of matching developer funds with the most impactful projects.

These citywide funds are a response to the question of “how can we make development writ large more inclusive?” as opposed to “how can we make a given development more inclusive?” These types of funds should not be the only or main mechanism for achieving inclusive development, but they should be a more important part of the portfolio of tools that cities and developers employ.

Investors, governments, and philanthropic foundations can provide minority developers with more capital. As described previously, BIPOC developers face many barriers and biases in their efforts to secure capital. According to a 2023 report by the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City and Grove Impact, of the 383 developers nationwide that generate more than $50 million in revenue, only one is Latino-owned and none are Black-owned.62 Addressing this profound disparity matters for at least two reasons. First, it would allow development—regardless of whether the development itself is inclusive— to help close racial wealth gaps. Second, it is likely—though not guaranteed, as one interviewer stressed—that developers of color may be more motivated to pursue more inclusive forms of development.

One example that reinforces the importance of public development authorities is a planned $50- million fund for developers of color led by the quasi-public Massachusetts agencies MassDevelopment and MassHousing.63 Allocated by the state legislature from its American Rescue Plan Act allotment, this fund will cover pre-development costs and provide grants and low- or no-interest loans. Developers could contribute to such funds as a way to broaden their support of BIPOC developers in addition to involving developers of color directly in their projects.

Cities can be more mindful of empowering small, emerging, minority-led, mission-driven developers like the Re:Land Group in Louisville with not only financial capital but “belief capital.” One interviewee said that a demand of city government was “don’t treat us like we’re just activists or just community members who have an opinion,” but instead as capable developers. Philanthropy, too, could invest more in capital for developers of color—not just those working on affordable housing projects but also those working on mixed-used, catalytic developments.

Conclusion

I’m watching government flounder, and I’m watching nonprofits flounder, and I’m watching philanthropy and developers fund the floundering.