In the past, driven by production cost advantages and an export-oriented trade policy, the manufacturing sector has always been at the center of Taiwan’s economic development; this was true during the first import substitution period (1950–1958), during the era of rapid export growth (1958–1969), during the second import substitution period (1969–1980), and during the era of trade liberalization (from 1980 to the present day). The more capital-intensive manufacturing industries continued to make Taiwan the main center of their development even though, faced with upward pressure on wages, manufacturers in labor-intensive industries that were competing largely on cost were forced to relocate production overseas (usually either to China or to Southeast Asia). Nevertheless, with the relocation of downstream manufacturing activities offshore and the general shift in emphasis within industry towards the upstream segments, there has been a transformation in Taiwan’s foreign trade linkages and in its position within the wider Asian production and supply chain.

The Transformation of Taiwan’s Role within the Supply Chain

(1) The structure of Taiwan’s exports is heavily oriented towards intermediate goods and capital goods, making for steadily closer direct trading links with other Asian countries.

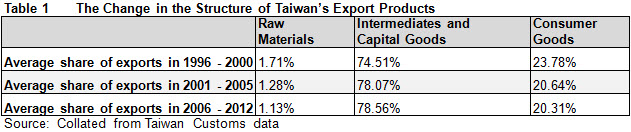

Examination of Taiwan’s export data for the period 1996–2012 shows a growing concentration of intermediate goods and capital goods in Taiwan’s export product mix. Over the years 2006–2012, nearly 80 percent of Taiwan’s exports fell into the intermediates and capital goods category (Table 1).

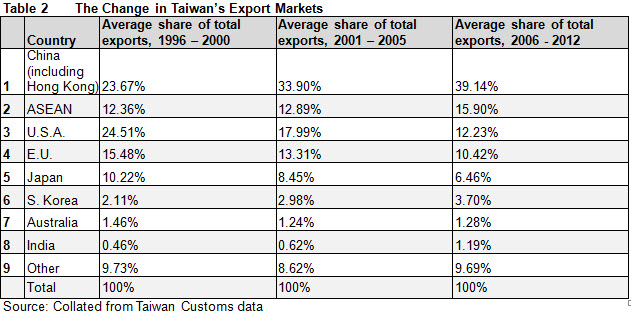

At the same time, there has been a steady fall in the share of Taiwan’s exports going to developed nations (including the European Union, the United States, and Japan), while the share of exports going to developing economies such as China, the ASEAN nations, and India has risen dramatically. Approximately 55 percent of Taiwan’s exports over the period 2006–2012 went to China or ASEAN (Table 2). The direct trading links between Taiwan and other Asian nations have thus been growing steadily closer and more intensive.

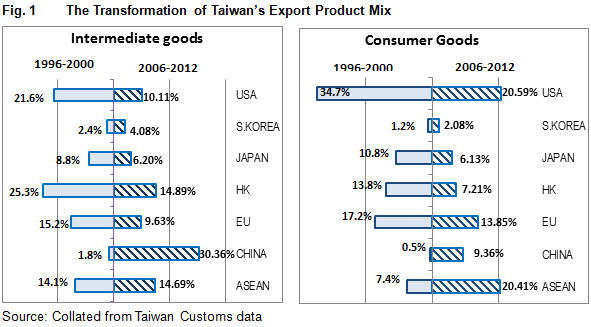

(2) A complex division of labor has developed between Taiwan and China, and while the ASEAN nations are not only part of the same supply chains as Taiwan, they also constitute important markets for Taiwanese goods. The European nations and the United States, by contrast, are largely just export markets for Taiwan, and show a pronounced fall in the volume of trade in intermediates and capital goods, and a weakening in direct trade links with Taiwan.

As can be seen from Fig. 1, there has been a steady increase in the shares of Taiwan’s intermediate goods and capital goods exports to China and the ASEAN member states; this trend is particularly pronounced with respect to China. By contrast, the share of total intermediates and capital goods exports to the E.U. member states, Japan, and the United States has been falling steadily. The United States, ASEAN, and the E.U. are Taiwan’s largest markets for final consumption goods, followed by China and Japan.

These data show that, with the changes in the production environment in Taiwan and the adjustment of Taiwan’s industrial structure, Taiwan has become more focused on the manufacturing of intermediates and capital goods. The positioning by Taiwanese companies of other Asian nations as locations for export processing activities, and the resulting stimulus to trade, has made the industrial division of labor between Taiwan and other Asian economies steadily more intensive. This is particularly true with regard to the industrial division of labor between Taiwan and China, but a similar trend can be seen between Taiwan and the ASEAN member states.

The United States and the E.U. have maintained their status as the most important markets for Taiwanese final consumption goods, but Taiwan’s exports of intermediates and capital goods to these countries have become less significant, and there has been a weakening in direct trade links between Taiwan and the E.U. and between Taiwan and the United States. On the other hand, indirect trading links between Taiwan and the E.U. and Taiwan and the United States by way of China or the ASEAN economies have been increasing. One point worth noting is that, over the past seven years, the share of Taiwan’s final consumption goods in exports to ASEAN has been similar to the corresponding percentage for Taiwan’s exports to the United States, indicating that, besides being engaged in an industrial division of labor with Taiwan, the ASEAN member states are now also important export markets for Taiwan’s final consumption goods.

There is a direct relationship between the pattern of trade that has emerged and Taiwan’s overseas investment. The main recipients of overseas investment by Taiwanese companies have been China and Southeast Asia. Broadly speaking, Taiwanese firms have viewed these two regions as locations for export processing, with intermediate goods and capital goods being shipped from Taiwan to China or Southeast Asia for use in the production of final consumption goods which are then exported to Europe or the United States, creating a “triangular trade” relationship. Despite the efforts made by Taiwan in recent years to develop other international markets, this triangular trade remains the basic pattern of Taiwan’s foreign trade.

However, this pattern of trade works to Taiwan’s disadvantage when the market for final consumption goods is affected by an economic downturn. Over the last few years, for example, the impact of the sub-prime mortgage crisis in the United States and of the European debt crisis led to a fall in shipments from China-based and ASEAN-based export processing sites to the European and U.S. markets; this period has also seen a pronounced decline in exports from Taiwan to China and to the ASEAN nations. This kind of “chain reaction,” spreading from the downstream segment up the supply chain, has a greater impact the closer to the top of the supply chain it gets – the so-called “bullwhip effect” – and has had serious negative effects on Taiwan.

(3) The electronics and IT sector accounts for a very large share of Taiwan’s overall production and exports, making Taiwan even more vulnerable to the impact of the global business cycle.

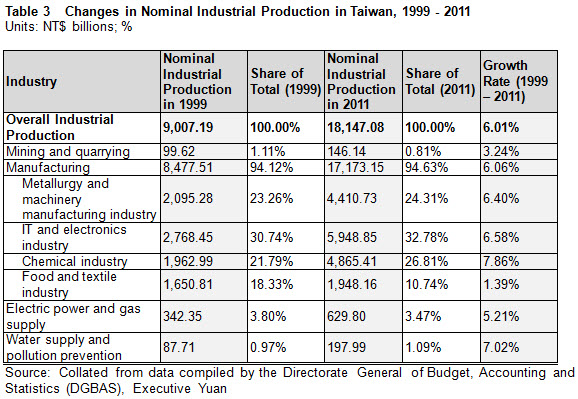

Economies of scale are extremely important for capital-intensive industries, and Taiwan’s economic development has become increasingly dependent on a handful of individual industries. As shown in Table 3, below, over the period 1999–2011, in terms of nominal production value the four industries that accounted for the largest shares of Taiwan’s overall output were the chemical industry (which had an average annual growth rate of 7.86 percent), the metallurgy and machinery industry (6.40 percent), the information and electronics industry (6.58 percent), and the food and textiles industry (1.39 percent; see Table 3). Given that the growth rates noted above are based on nominal production value, if inflation is taken into account then the 1.39 percentage average annual growth rate of the food and textiles industry actually represents a pronounced decline in real output over this period. The metallurgy and machinery industry has also experienced some degree of stagnation; the manufacturing of industrial machinery has become less important to the industry, while the shares of the industry’s output held by machine tools, electronics, and semiconductor manufacturing equipment (and related components) have risen.

The center of gravity in the Taiwanese manufacturing industry has been shifting gradually towards two key industries: chemical materials, and the manufacturing of new types of electronic components. Of these, while the chemical industry remains prominent at the present, the relocation of production to offshore locations in Taiwan’s garment, shoe, bag, toy, and electronic device industries―coupled with rising environmental consciousness―is creating obstacles to the chemical industry’s continued development; the chemical industry has also been affected by the dramatic decline in the production value of the downstream plastics manufacturing industry.

Overall, Taiwan’s industrial structure has increasingly come to be dominated by the IT and electronics sector (partly due to the impact of the government’s industrial policy). As a result, IT and electronics products now account for an excessively large share of Taiwan’s overall exports. Based on export data compiled by Taiwan’s Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), it can be determined that, throughout the period from 2000 to 2012, exports of electronics, IT, and communications products consistently accounted for over 30 percent of Taiwan’s total exports. As IT and electronics products are characterized by a high level of income elasticity, consumers will often delay purchase of these items. Fluctuations in the global economic climate can thus have a significant negative impact on Taiwan’s exports and its economic growth rate; Taiwan’s ability to implement adjustments in response to global economic fluctuations is also affected.

There is Considerable Room for Improvement in the Level of Value-added in Taiwan’s Manufacturing Sector

In the past, Taiwan’s manufacturing industries tended to focus mainly on expanding their production volume, with relatively little attention being paid to enhancing product value-added (e.g. by adopting a differentiation strategy, adding value through design, own brand development, integrating manufacturing with services, etc.). As a result, there is still considerable potential for improvement in the creation of added value by Taiwan’s manufacturing sector. The failure to raise value-added in manufacturing has had a knock-on effect on the terms of trade[1] for Taiwan’s export products. According to DGBAS statistics, there has been a steady deterioration in Taiwan’s terms of trade, with profits deriving from terms of trade falling from NT$754.9 billion in 2001[2] to zero in 2007. By 2011, Taiwan was suffering a loss deriving from terms of trade that amounted to NT$1,489.4 billion, showing how the gradual deterioration in the terms of trade for Taiwan’s main export products has worsened. With this worsening in the terms of trade, the growth in the real incomes of Taiwan’s citizens has failed to keep pace with the economic growth rate, which in turn has had a negative impact on consumer spending and investment.

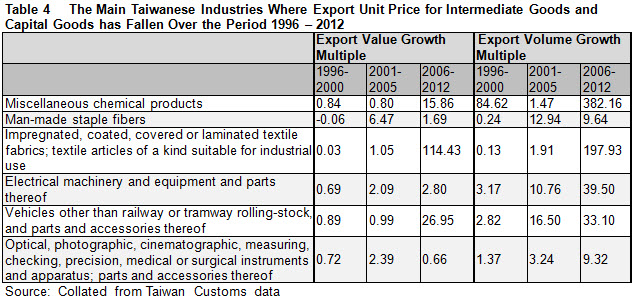

As can be seen from the data in Table 4, below, relating to the changes in the export performance of Taiwan’s main industries over the period 1996 – 2012, with respect to the core portion of Taiwan’s exports (i.e. intermediate goods and capital goods), for the five major industries listed in the table – miscellaneous chemical products, man-made staple fibers, industrial textiles, electric machinery and equipment (and parts thereof), vehicles, and optical and precision instruments etc. – the growth in export volume over the periods covered by Table 4 was significantly higher than the growth in export value, indicating that the export unit price for these industries’ products has been falling over this period.

Furthermore, DGBAS data show that, over the period 1999–2011, the nominal production value growth rate for Taiwan’s IT and electronics industry was only 6.58 percent, lower than the real production value growth rate of 9.37 percent. This implies negative growth in average unit price in Taiwan’s IT and electronics industry, a phenomenon which reflects an erosion of the industry’s earning performance and a failure to raise the industry’s value-added.

The data presented above reflect the fact that, for many years, Taiwanese manufacturers relied mainly on an OEM[3] contract manufacturing business strategy. The main focus in contract manufacturing was on raising the efficiency of production processes, rather than on developing key technology or researching the end-user market. Lacking key technology, and without their own brands and distribution channels, most Taiwanese manufacturers have had to resort to competing on price; as a result, the Taiwanese manufacturing sector as a whole has failed to achieve any significant enhancement of its value-added. Even the IT and electronics industry – which has been the main focus of the government’s industrial policy and guidance efforts – has largely failed to move beyond the contract manufacturing model.

Taiwan’s Position within the Industrial Division of Labor in Asia is Being Challenged

Taiwan’s manufacturers now find themselves facing increasingly serious competitive pressure not only from China but also from other emerging economies in the region. As noted above, Taiwan’s industrial development having been heavily concentrated in the IT and electronics sector; a complex division of labor has developed between Taiwan and China, as China’s own industry has grown; and the Taiwanese manufacturing industry has failed to raise its value-added and continues to lack key technology, brands and distribution channels. Over the next few years, some Taiwanese products will see their position within the industrial value chain being eroded, and Taiwan will gradually lose its place as a key player in export processing.

At the same time, there is a marked global trend towards regional economic integration, with countries throughout the world rushing to negotiate free trade agreements (FTAs) with one another. Regional integration has been progressing particularly rapidly in Asia, but Taiwan is excluded. As the FTAs being signed in the Asia region re-make the regional division of labor, Taiwan’s position within the international manufacturing division of labor is coming under increasingly serious threat.

Looking in more detail at the challenges that regional economic integration can be expected to pose for Taiwan in the future, the key factor here is the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which is currently the most significant regional trade arrangement in the Asia Pacific region. The TPP already has 12 member nations (the U.S.A., Japan, Canada, Mexico, Canada, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, Australia, New Zealand, Chile and Peru), and has been advocating a strengthening of the intra-regional supply chain. This means that, in the future, the TPP can be expected to implement strict rules of origin provisions, which will promote the development of the intra-regional division of labor, but which may have a severe negative impact on Taiwan (which is likely to find itself excluded from the TPP).

Taking Taiwan’s textile industry as an example, currently Taiwan exports large quantities of yarn and fabric to Vietnam, where it is processed into garments for export to the United States. Under the current “yarn forward” approach adopted for the TPP’s rules of origin in relation to garment manufacturing, Vietnam will be required to use yarn produced in another TPP member economy in order to benefit from preferential tariff treatment when exporting garments to the United States. This will led to the disruption of the existing Taiwan ® Vietnam ® U.S. supply chain, with Taiwan suffering the most serious negative impact. Given the strictness of the TPP’s rules of origin requirements, a similar situation is likely to emerge in other industries. Overall, the impact on Taiwanese manufacturing impact may be very severe.

How Taiwan Can Respond

Faced with the trends outlined above, over the long term, Taiwan will need to rethink the way it interacts with the wider global economy. There are three key areas that need to be addressed:

(1) Encourage Taiwanese companies to develop their own brands

The main priority is to change the model under which Taiwanese enterprises interact with the global economy, with a shift away from contract manufacturing towards own-brand development. In the past, Taiwanese industry has always been oriented mainly towards ODM/OEM contract manufacturing, with Taiwanese firms acting as one part of the supply chain for leading international brands. The advantage of this model is that Taiwanese enterprises have been able to concentrate on manufacturing itself, making effective use of Taiwan’s abundant high-quality labor and superior management skills, to exploit Taiwan’s cost advantages to the maximum. The disadvantage is that Taiwanese manufacturers have failed to develop their own core technology, remaining dependent on overseas technology and foreign-made production equipment, while undertaking only very limited innovation and R&D, and as a result creating relatively little value-added. As a result, profit margins have generally been low. Furthermore, if demand for the big international branded vendors’ products starts to fall, the survival of the Taiwanese contract manufacturers may be threatened. This contract manufacturing model is one of the main factors behind the recent fall in Taiwan’s exports (and the negative impact that this has had on Taiwan’s economic growth).

Moving away from contract manufacturing towards own-brand development can help Taiwan move beyond having only a “shallow” economic structure. Besides technological improvements, this transformation will also require new ways of thinking, to enable Taiwanese manufacturers to move from imitation to innovation, from assembly to marketing, and from being integrated into someone else’s supply chain to being the ones doing the integrating. Taiwanese firms will also need to reposition themselves away from business-to-business (B2B) contractual relationships towards business-to-consumer (B2C) relationships, and replace their emphasis on “cost down” with a new emphasis on “value up.”

Faced with the challenge of upgrading itself, Taiwanese industry needs to move away from being production-oriented (focusing on reducing production costs) towards being market-oriented (emphasizing value creation and service provision). The rapidly growing Asian market can provide Taiwanese companies with exactly the platform they need to make this transformation. Despite the fact that globalization appears to be going into reverse, the global market is still important; nevertheless, establishing a strong position in one’s own regional market is the first step towards successful branded marketing.

After many years of hard work, Taiwan has succeeded in establishing a number of global brands (such as Acer, ASUS, HTC, etc.). However, achieving any significant further increase in the number of globally-recognized Taiwanese brands is likely to be a difficult task. Building regional brands may be a more realistic proposition. A number of Taiwanese companies have already succeeded in building up their own brands in the China market. While these brands may have difficulty developing the wider global market, if they focus on the Asian regional market, their chances of success are much higher.

The development of regional brands is perhaps even more important for companies in the service sector than it is for manufacturers. The service sector now accounts for over 70 percent of Taiwan’s GDP, but so far it has had relatively little success in developing export markets. In the short term, it may be beyond Taiwan’s powers to develop a service sector capable of exporting its services all over the world, but exporting to other parts of the Asia region may be more practicable. If Taiwan’s service sector fails to develop a meaningful export capability, then it will find it hard to build economies of scale, which in turn will hinder the raising of productivity, so that the jobs created in the service sector will remain mostly low-wage, low-end jobs; this in turn will have a negative impact on income distribution within Taiwan.

(2) Develop a more diversified industrial structure

Besides changing the model through which it engages with the global economy, Taiwan should also be working to expand the scope of its engagement. One of the main reasons why the recent global financial crisis had such a severe impact on Taiwan was that Taiwan’s industrial structure is too heavily oriented towards the production of IT and electronics products, with insufficient diversification. In the future, Taiwan will need to take advantage of the new trends in global markets by working actively to develop not only new products but also new-generation industries. In the past, when Taiwan’s IT and electronics sector was at the peak of its success, Taiwan was already seeking to identify new industries that could continue to drive Taiwan’s growth in the future, but so far the results achieved have been rather disappointing. In the future, Taiwan should seek to take advantage of the new opportunities to develop the cultural and creative industries, alternative energy, biotechnology and other emerging industries, so as to give Taiwan a more diversified industrial structure.

(3) Work actively to negotiate FTAs

Taiwan should be working actively to forge partnerships with other countries and secure the reduction of barriers to trade, so as to maintain the competitiveness of Taiwanese exports. Taiwan needs to be negotiating regional trade agreements that provide for mutually-beneficial market opening, together with bilateral market opening that can boost Taiwan’s exports, as a proactive response to the situation in which Taiwan finds itself today.

Taiwan’s efforts to secure greater participation in the process of regional economic integration are often hampered by non-economic factors. Nevertheless, Taiwan should still be taking the necessary steps in preparation for greater liberalization, particularly since the scope covered by FTAs is tending to grow steadily wider, addressing not only market opening but also regulatory reform, an area where there is still much work to be done in Taiwan.

[1] Terms of trade (TOT) is defined as the radio of export prices to import prices. It can be considered as the amount of import goods a country can purchase per unit of export goods.

[2] Figure based largely on trade balance calculated from export and import deflators.

[3] An original equipment manufacturer, or OEM, manufactures products or components that are purchased by another company and retailed under that purchasing company’s brand name.

Commentary

Op-edThe Transformation of Taiwan’s Status Within the Production and Supply Chain in Asia

December 4, 2013