Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

This piece was originally published in French in Le Monde Diplomatique and has been translated in English and Arabic.

Upon welcoming Prime Minister Saad Eddine El-Othmani in Beijing on September 5, 2018, to commemorate the 70th anniversary of establishing relations between China and Morocco, President Xi Jinping stressed that his country “considers Morocco as an important partner in building the Belt and Road Initiative [BRI]” – the name by which the Chinese government calls its “new silk roads” project.

A few months later, in February 2019, the tourist town of Chefchaouen, in northern Morocco, was adorned with 1,500 red lanterns to celebrate the Chinese Spring Festival. That was something unheard of. The local press, which extensively reported on the event, did not hesitate to emphasize the gradual strengthening of the Chinese presence in Central Maghreb and, more generally, in North Africa.

Although the projects are still modest, countries such as Egypt, Algeria and Morocco have become part of China’s increasing engagement in this strategic region, located at the crossroads between the Middle East, Africa, Southern Europe and the Mediterranean. Key sectors in this growing footprint include trade, infrastructure development, port construction, as well as the launch of new maritime links, financial cooperation, tourism and manufacturing.

To distinguish itself from its Western competitors, Beijing relies on two major arguments. First, the official policy of non-interference in the internal affairs of the countries it is dealing with. This, for China, is an attractive alternative to the normative engagement that often characterizes cooperation with the United States and the European Union; Rabat, Tunis or Cairo sometimes find the association treaties signed with the Union to be too restrictive 1. The second argument is the pragmatism and opportunism of Chinese politics. Since decision-making is part of a highly hierarchical chain of command, investment choices can be quick, while in the West, validation often takes a long time. In addition, China boasts an unmatched ability to provide cheap financing and labor for infrastructure development – an area in which the United States and Europe cannot compete. This was the case, for example, during the construction of several thousand homes in Algeria between 2002 and 2010. From January 2005 to June 2016, China won 29 major contracts worth $22.22 billion.2

China’s relationship with the countries of North Africa, especially Algeria and Egypt, began during the anticolonial struggle, stemming from an ideological support for national liberation movements. Notably, China was the first non-Arab country to recognize the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (PGAR, 1958-1962) and provided much-needed diplomatic support to the independence war led by the National Liberation Front (NLF, 1954-1962). Gamal Abdel Nasser was the first Arab and African leader to recognize the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1956. While China did not play as important a role as the Soviet Union, the PRC was a strong supporter of the Egyptian president during his many confrontations and arm-wrestling with the West.

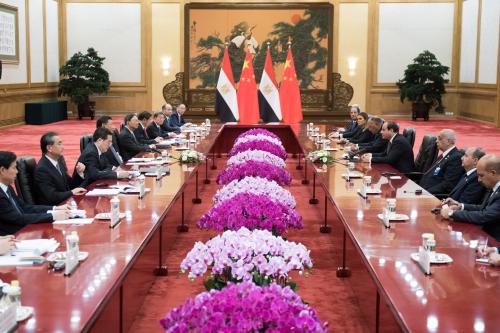

But it was at the beginning of the millennium that China began to turn its attention toward this region for economic reasons. The BRI is a symbol of this shift. While South Asia has so far received the majority of BRI projects, the initiative’s expansion west, toward Europe and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, is well underway. Beijing established a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) with Algeria, as well as with Egypt in 2014, and a Strategic Partnership (SP) with Morocco in 2016. However, it is with Egypt that trade is most developed, with Chinese sales exceeding $8 billion a year. Capital flows also continue to increase. In November 2018, Secretary General of the Union of Arab Banks Wissam Fattouh noted that investments had reached $15 billion.3 They are officially intended to finance real estate and infrastructure projects for the new administrative capital northeast of Cairo, a petrochemical plant, a possible water treatment and storage station and a coal-fired power station.

Algeria is one of Beijing’s oldest and most important economic partners in the region. China is interested in the country’s vast oil and gas reserves. Chinese imports to this energy-producer are the highest in the Maghreb, recorded at $7.85 billion in 2018. China became Algeria’s top trade partner in 2013, surpassing France. In Algeria, Chinese companies are primarily interested in the construction, housing, and energy sectors. Major construction projects, such as the Algiers Opera House, the Sheraton Hotel, the Great Mosque of Algiers and the East-West Highway, mark the landscape. These activities have brought in thousands of workers and merchants who have established a “Chinatown” in the district of Boushaki, in the eastern suburbs of Algiers. On several occasions, fights broke out with locals, particularly in the summer of 2009 and in the summer of 2016. This presence remains a recurring cause of tension.4

Since King Mohammed VI visited China in 2016, investment and trade have also increased in Morocco. The Tangiers Med Port Complex in the North has become the largest container port in Africa, ahead of rivals Port Said (Egypt) and Durban (South Africa). Chinese companies, such as telecommunications giant Huawei, plan to establish regional logistical headquarters there. On the 10th anniversary of the port’s opening, Rabat announced a $10 billion investment project, named Mohammed VI Tangiers Tech City, which is set to host two hundred factories in the next ten years, making Morocco Africa’s largest Chinese industrial platform.5

China is also seeking to deepen its trade with Tunisia and Libya. In 2018, it signed BRI MoUs with these two countries.6 With Tunisia, Chinese imports have reached an annual average of $1.85 billion since 2016, ranking third behind France and Italy. After the outbreak of the civil war in Libya in 2011, Beijing had to evacuate its citizens and drop important projects and investments. However, its Libyan oil purchases have more than doubled since 2017. The Chinese government has repeatedly stated that it is willing to participate in the reconstruction effort once peace is restored.7

China has also invested in maritime projects, via the China Ocean Shipping Company (COSC), in the ports of Tangiers, Cherchell (Algeria), Port Said and Alexandria, Piraeus (Greece), as well as in ports in Israel, Turkey and Italy. The country also specializes in laying submarine cables, a crucial element of its telecommunication development strategy. Huawei Marine Networks designed and installed the “Hannibal” cable linking Tunisia to Italy in 2009, as well as another cable linking Libya to Greece in 2010. This intense activity raises a number of concerns in Europe, where there are fears that Beijing takes advantage of these projects for intelligence gathering. Concerns increased when Sri Lankan officials claimed that the Chinese insisted on an intelligence-gathering component that would monitor all traffic through the port of Hambantota, which it took full control of in 2017, in exchange for relieving the country from a debt amounting to $1.2 billion.8

China is also seeking to increase its influence in the region through a stronger cultural engagement. As part of an MoU signed between the King of Morocco and President Xi in 2016, a China Cultural Center was inaugurated in Rabat in December 2018. Meanwhile, Egypt is home to two Confucius Institutes, located at Cairo University and the Suez Canal University, as well as to a Chinese cultural center in the capital. In Tunisia, the first Confucius Institute opened in November 2018. During the 2018 Beijing Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), the Chinese government also decided to increase the number of scholarships awarded to African students, including those from the North of the continent, to enable them to pursue higher education in China – promising 50,000 government scholarships and another 50,000 training grants. For African students, China is now the second destination after France; their number went from 2,000 in 2003 to nearly 50,000 in 2015, a 25-fold increase.

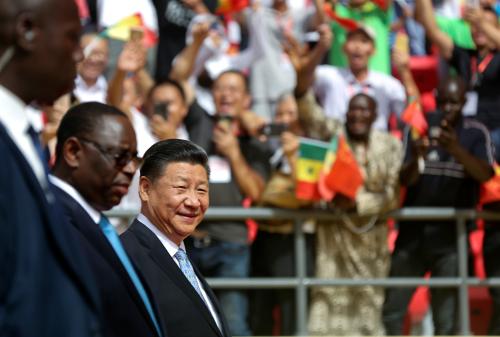

To build its influence, Beijing has established regional organizations such as the FOCAC and the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF), even though it currently deals with each North African country through a largely bilateral framework. This diplomatic engagement illustrates the principle of xinxing daguo guanxi, or “a new type of major power relations,” whereby China seeks to engage with less important countries once they have been grouped into major regional forums.9 Only then are they considered to be powerful enough for high-level cooperation.

As for military operations, China’s first significant military action in the region took place in Libya in 2011, when the People’s Liberation Army (PLN) helped to evacuate thousands of Chinese workers from the country before NATO airstrikes began. Subsequently, in 2015, a joint Chinese-Russian military exercise took place in the Mediterranean and, in 2017, China opened its first overseas military base in Djibouti, putting the eastern Mediterranean coast within reach of its navy and air force. In January 2018, two warships from the 27th Chinese naval escort stopped by Algiers for a four-day “friendly visit” as part of a four-month tour.

In just two decades, China has strengthened its position in North Africa. However, it is still too early to reach a definitive conclusion about the implications of this engagement. Nonetheless it is important to evaluate potential long-term impacts on these countries and their finances, especially if these funded projects are not integral to these countries’ development strategies. Similarly, strategic investments, especially in ports, will continue to fuel concerns of Western countries, which are well aware that such infrastructure can easily be used for security purposes.

-

Footnotes

- Béligh Nabli, « Accord et désaccord entre l’Europe et la Tunisie », L’Économiste maghrébin, Tunis, 26 février 2016.

- Hassan Haddouche, « La Chine en Algérie : le commerce en attendant les investisseurs », Tout sur l’Algérie, 9 mai 2018.

- « Chinese investments in Egypt hit $15 B », Egypt Today, Gizeh, 14 novembre 2018.

- Célian Macé, « À Alger, “au fond, on ne veut pas des Chinois” », Libération, Paris, 6 septembre 2017.

- Hayat Gharbaoui, « Tanger Tech : le chinois CCCC exige les mêmes avantages que Renault et PSA », Médias24, 30 avril 2019.

- Lamine Ghanmi, « Tunisia joins China’s Belt and Road Initiative as it seeks to diversify trade, investment », The Arab Weekly, Londres, 9 septembre 2018.

- Safa Alharathy, « Libya joins China’s Belt and Road Initiative », The Libya Observer, Tripoli, 13 juillet 2018.

- Maria Abi-Habib, « How China got Sri Lanka to cough up a port », The New York Times, 25 juin 2018.

- Alice Ekman, « China’s regional forum diplomacy », Institut d’études de sécurité de l’Union européenne, Paris, 24 novembre 2016.

Commentary

Op-edBeijing strengthens its presence in the Maghreb

Monday September 9, 2019