I want to begin by saying how grateful we were at Brookings to partner with the Federal Reserve System on this concentrated poverty project. We like to think that at Brookings we know a lot about this subject, but it was only through this partnership with the Fed that we were able to ground this understanding in the experiences of the 16 communities across the United States that were the focus of the report’s case studies.

The report demonstrates that in addition to managing the macroeconomy, the Fed also possesses a unique and powerful understanding of the U.S. economy from the ground up, which is absolutely necessary for designing smart policy in turbulent times like these.

I want to also give special thanks to my colleagues David Erickson and Carolina Reid at the San Francisco Fed. They played several roles in this project for me: intellectual partners, co-conspirators, mood lighteners, and Fed sherpas. It can be tough for foreigners like myself to navigate this system, and they lightened my load throughout the project. I also want to thank my Brookings colleague Elizabeth Kneebone, who performed a lot of the data analysis for this project.

I want to argue three points, largely policy points, in my remarks this morning.

First, the current economic climate makes the issue of concentrated poverty, and our response, more relevant, not less.

Second, major near-term investments our country makes to resolve the economic crisis can and should provide meaningful opportunities for the most disadvantaged families and communities.

And third, our longer-run efforts to assist high-poverty areas and their residents must take account of the economic challenges and opportunities that manifest at the regional, metropolitan level.

To begin, let’s review where we were when the Fed and Brookings joined forces on this effort in May 2006.

- The unemployment rate was 4.7 percent, a five-year low.

- Payrolls were expanding every month for the third consecutive year.

- The poverty rate, while still above its low in 2000, was dropping.

- The federal deficit was a relatively manageable 2% of GDP.

- The Dow was above 11,000, and on its way up.

- And the 2008 general election promised a storied matchup between party favorites Hillary Clinton and Rudy Giuliani.

A lot can happen in 30 months!

In the wake of record house-price declines and financial market fallout, the economic outlook today is grim. The unemployment rate is 6.5 percent and rising. One projection suggests that the downturn could eventually increase the ranks of the nation’s poor by anywhere from 7 to 10 million. And amid declining revenues and increased expenditure needs, the U.S. budget deficit is expected to top $1 trillion this year.

In short, the situation for the lowest-income communities and their residents is not encouraging.

And neither is our starting point.

As Paul Jargowsky’s research has shown, the incidence of concentrated poverty in America dropped markedly during the 1990s, after two decades of increase. Some combination of a tight labor market and policy changes to promote work and break up the deepest concentrations of poverty seemed responsible for that decline.

But as Elizabeth and I found in a recent Brookings report, we may have given back much of that progress during the first half of this decade. The population in what we termed “high working poverty” communities rose by 40 percent between 1999 and 2005. This suggests that America’s high-poverty areas may have never really recovered from the modest downturn we experienced at the beginning of the decade.

Now, with all the turmoil in our economy, it would be easy to lose sight of these places and their residents, who even seem to have missed out on the benefits of recent growth.

But if we are to meet the enormous challenges facing our country—economic, social, and environmental—we simply can’t afford to take a blind eye to the continuing problem of concentrated poverty.

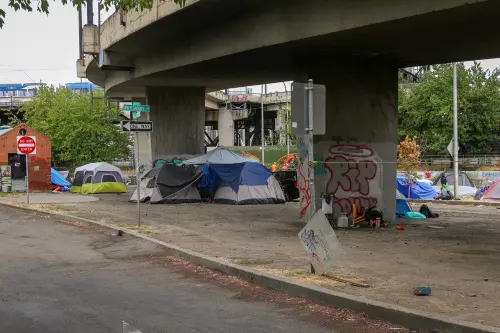

As decades of research and this report have shown, concentrated poverty magnifies the problems faced by the poor, and exacts a significant toll on the lives of families in its midst.

This report greatly enhances our understanding of how high-poverty communities of all stripes bear these costs. Moreover, it suggests that the contemporary circumstances of these communities owe not just to long-term market dynamics, but also to policy choices made over several decades’ time—some deliberate in their intent, and some producing unfortunate unintended consequences.

Today we’re at an important inflection point for policy. With the economy souring, we don’t have the luxury of using an “auto-pilot” strategy of macroeconomic growth to reach the most disadvantaged places and their residents. Quite the opposite—just as these communities are often “last in” for economic opportunity during boom times, they seem to be “first out” when things shift into reverse.

But the specific nature of the current crisis also poses added challenges for high-poverty communities.

That is because many of these areas were ground zero for risky subprime lending over the last several years. In many of the case-study communities in the report, half or more of recent home mortgages were high-cost subprime loans.

Now, they are on the front lines of the fallout. Our calculations of HUD data show that census tracts where the poverty rate was at least 40 percent in 2000—the conventional definition behind concentrated poverty—have an estimated foreclosure rate over 9 percent, roughly double the nationwide average.

This poses both an immediate and a long-term threat to what little stability these communities possess.

Over the short term, these areas face problems associated with heightened property neglect, vacancy, and abandonment. Not only can those conditions breed crime and disorder, but also they can accelerate a process of further disinvestment from high-poverty neighborhoods, which are all too familiar with that cycle of decline.

Over the long run, the public sector will work to return foreclosed properties in these neighborhoods to productive use. But there is a danger that we may once again re-concentrate poverty in these neighborhoods if these assets are not managed and deployed strategically.

In sum, recent trends and a perilous road ahead merit a meaningful policy response to the challenges facing areas of concentrated poverty and their residents.

This brings me to my second point, which is that near-term policy choices can ameliorate the impacts of the current crisis on areas of concentrated poverty.

In less than 50 days, a new administration will take office in Washington, facing economic challenges of a scale not seen in decades.

The president-elect and his advisors have signaled that they are ready to “do what it takes” to stimulate the economy, create and protect jobs, and catalyze investment in new sectors to spur longer-term growth.

I believe that policies advanced by the new administration and Congress in the first few weeks of the new year, if designed and executed well, could matter greatly for the fortunes of the nation’s high-poverty communities.

First, a comprehensive strategy to deal with the foreclosure crisis is sorely needed. This would feature, first and foremost, a broad plan to forestall the rising tide of mortgages, including many in high-poverty communities, headed for default due to falling home prices, economic dislocation, and poor underwriting.

However, even a sweeping, generous approach will not prevent the inevitable. Especially in high-poverty areas, more loans will fall into foreclosure, more people will lose their homes, and fiscally-strapped local governments will be left to manage the consequences of increasing vacancy and abandonment.

The Neighborhood Stabilization Program enacted by Congress and the Bush administration during the summer of 2008 represents an initial effort to arm state and local leaders with the resources to tackle the neighborhood impacts of rising foreclosures.

But significant deterioration of the economy in the intervening months suggests that the problem may now be of a much larger scale than was originally anticipated. What’s more, many local governments lack the capacity, expertise, and legal authorities to use existing or additional resources strategically.

So the new administration, and HUD in particular, will need to consider a further round of response—using some mix of fiscal, regulatory, capacity-building, and bully pulpit powers—to help cash-strapped local governments mitigate the impacts of foreclosure on their most vulnerable communities.

Second, there seems to be wide agreement that the economic recovery package should include a series of measures that inject money into the economy right away.

So the package will provide immediate assistance to families, communities, and governments hit hard by the downturn, in the likely form of extended unemployment and increased food stamp benefits, increased state and local aid, and low- to middle-income tax cuts, spending designed to make a real economic impact in the next several months.

A couple of details here are of real consequence to communities of concentrated poverty.

- Income tax cuts included in the package should be refundable, like the Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC. Boosting the EITC, for instance, would provide additional help to workers most likely to be hit hard by the downturn, and target resources to families most likely to spend the additional cash immediately. As the report shows, at least 30 percent, and as many as 60 percent, of families in the case-study communities today benefit from the EITC.

- Unemployment insurance benefits should be extended, but also modernized. As the case studies showed, work among residents of high-poverty communities is often seasonal or part-time, even in a good economy. As a result, many laid-off workers from poor areas in several states may not qualify for benefits due to outmoded eligibility rules. Therefore, in addition to extending weeks of eligibility for UI, Congress and the new administration might also consider providing incentives to states to expand the pool of workers who could benefit from the program during the downturn.

Third, infrastructure will clearly figure prominently among the spending priorities in the recovery package.

Yet there is a significant risk that focusing dollars primarily on projects that states deem “shovel-ready,” as has been discussed, will repeat mistakes of the past. It would primarily subsidize road-building at the metropolitan fringe, and do little to enhance long-run economic growth, or provide better opportunities for low-income people and the places they live.

Infrastructure investments of the magnitude under consideration must not only create jobs, but also promote inclusive and sustainable growth. That means setting strict criteria for federal investment, including a real assessment of costs and benefits that considers economic, environmental, and social impacts. As the report shows, poor infrastructure often acts as a barrier to the economic integration of high-poverty communities into their larger municipal and regional areas.

To that end, we should also consider providing direct support for large, cash-strapped municipal governments that they could use to modernize and preserve roads, bridges, transit, water, sewer, and perhaps even broadband infrastructure. At the same time, we should hold them and grantees at all other levels of government accountable for connecting younger, disadvantaged workers and communities to the jobs that result.

In short, what happens in the first several weeks of the new year here in Washington could, if structured properly, provide meaningful support and opportunity for low-income areas and their residents. At a minimum, this might avert the sort of backsliding these communities suffered during the much milder recession we experienced earlier this decade.

So that brings me to my third and final point, which is that, over the longer term, we must advance policies that actively link the fortunes of poor communities to those of their regional neighbors. As you probably heard or read, our division at Brookings is named the “Metropolitan Policy Program.”

Our mission is to provide decision makers with cutting-edge research and policy ideas for improving the health and prosperity of cities and metropolitan areas.

You might ask, why metropolitan? After all, this is not a term that most Americans use, think about, or even recognize, even though 85 percent of us live in metropolitan areas. A friend of the program once told us that it sounded like a combination of “metrosexual” and “cosmopolitan.” Not exactly what we were going for.

More specifically, what relevance does “metropolitan” have for addressing the challenges of concentrated poverty?

Well, the report points to skills and employability problems that hold back residents of high-poverty communities. If the route to improving the lives of families affected by concentrated poverty runs in part through the labor market, then we must devise strategies and solutions that respect and respond to the geography of that market—which is metropolitan.

The report also points to housing problems, of various stripes, that segregate the poor in these communities and make their daily lives more difficult. Housing markets, too, are metropolitan—and housing dynamics in the wealthiest parts of each metro are inextricably linked to those in the poorest parts.

The fact is, our national economy—and that of most industrialized nations—is largely the aggregate of its individual metropolitan economies. In the United States, the 100 largest metro areas account for 12 percent of our land mass, hold 65 percent of our residents, and generate three-quarters of our Gross Domestic Product. They possess even greater shares of our innovative businesses, our most knowledgeable workers, the critical infrastructure that connects us to the global economy, and the quality places that attract, retain, and enhance the productivity of workers and firms.

And as the report shows, regions—both metropolitan and non-metropolitan—each retain distinctive clusters that shape their individual contributions to the national economic pie. Photonics in Rochester. Hospitality and tourism in Atlantic City and Miami. Manufacturing in Albany, Georgia. Agriculture and business services in Central California. These clusters do not possess equal strength or equal potential, but they define the starting point for thinking about the regional economic future of these areas, and economic opportunities for their residents.

Not only are the assets of our economy fundamentally metropolitan… increasingly, our challenges are, too. In 2006, we found that for the first time, more than half of the poor in metropolitan America lived in suburbs, not cities. While poor suburban families don’t yet concentrate at the levels seen in the communities in this report, they are trending in this direction. Between 1999 and 2005, the number of suburban tax filers living in “moderate” working poverty communities rose by nearly 50 percent.

So what does recognition of our metropolitan reality imply for longer-run policies to help the poorest communities and their residents?

Bruce has argued elsewhere that our nation must embrace a new, unified framework for addressing the needs of poor neighborhoods and their residents. He has termed this, Creating Neighborhoods of Choice and Connection. Neighborhoods of choice are communities in which lower-income people can both find a place to start, and as their incomes rise, a place to stay. They are also communities to which people of higher incomes can move, for their distinctiveness, amenities, or location. This requires an acceptance of economic integration as a goal of housing and neighborhood policy.

Neighborhoods of connection are communities that link families to opportunity, wherever in the metropolis that opportunity might be located. This requires a much more profound commitment to the “educational offer” in these communities and the larger areas of which they are a part. It also requires a pragmatic vision of the “geography of opportunity” with regard to jobs, housing, and other choices.

If we take this vision seriously, then our interventions must operate within, and relate to, the metro geography of our economy. This means viewing the conditions and prospects of poor areas through the lens of the broader economic regions of which they are a part, and explicitly gearing policy in that direction.

A simple example relates to the geography of work. In the Springfield, Massachusetts metro area, roughly 30 percent of the region’s jobs still cluster in the neighborhoods close to downtown, including Old Hill and Six Corners. In the Miami metro area, by contrast, only 9 percent of the region’s jobs lie close to its downtown, implying transportation needs of a quite different scale for Little Haiti’s residents. In response, we should empower metropolitan transportation planners to address the unique nature of these spatial divides, and measure their performance on creating inclusive systems that overcome them.

This metro lens applies to workforce development as well. Labor market intermediaries are some of the most promising mechanisms for bridging the information and skills divide between poor communities and regional economic opportunity. One of the highest performers, the Wisconsin Regional Training Partnership, works in the home region of one of our case-study communities, Milwaukee. If workforce policies and funding at all levels of government were to emphasize employer partnerships, provide greater flexibility, and reward performance, we could grow more capable institutions like these that serve the needs of low-income communities and regional firms alike.

A metro perspective can apply to school reform as well. We have called for a new focus at the Department of Education on supporting proven, successful educational entrepreneurs—charter management organizations like KIPP, human capital providers like Teach for America, student support organizations like College Summit. The demand for these entrepreneurial solutions extends well beyond the highest-poverty neighborhoods. Federal education policy should consider investing in these entrepreneurs at the metropolitan scale, to aggregate a critical mass of those organizations, serve a significant percentage of the area’s children, and drive positive changes in the entire public education environment.

Finally, our housing policies must embrace metro-wide economic diversity, which is a hallmark of neighborhoods of choice and connection.

This means expanding housing opportunities for middle-income families in deprived neighborhoods. We simply cannot continue to cluster low-income housing in already low-income areas, perpetuating the sort of economic segregation evident in so many of the case-study communities, and thereby consign another generation to a childhood amid concentrated poverty. Likewise, we must guard against the possibility that the current foreclosure crisis leads to a re-concentration of poor households in neighborhoods that were just beginning to achieve greater economic diversity.

But this is a two-way street. It also means creating more high-quality housing opportunities for low-income families in growing suburban job centers. Requiring or providing incentives to metropolitan areas to engage in regional housing planning, alongside regional transportation planning, may be a necessary first step. Those plans could also apply a more rational screen to the development choices that have fueled sprawl, and thereby added to the social and economic isolation of the lowest-income communities.

Let me end where I began.

This is both an auspicious and a challenging moment at which to wrestle with the problem of concentrated poverty in America.

Auspicious in that we are approaching the dawn of a new government in Washington that has signaled concern for our nation’s low-income residents and communities, recognition that metropolitan economies are the engines of our prosperity, and a pragmatic commitment to doing what works.

Challenging in that making progress against concentrated poverty, and improving opportunity for those in its midst, is a tall order when the macroeconomy isn’t cooperating.

But the current economic climate is not an excuse to avoid this problem; rather, it’s an imperative to act, strategically and purposefully.

That means doing the big near-term things the right way, so that low-income communities and their residents do not bear an excessive brunt of the downturn, and so that they participate meaningfully in our eventual economic recovery.

And it means getting the long-term vision right, so that policy advances sustainable, metro-led solutions that connect poor neighborhoods and poor families to opportunity in the wider economy around them.

The Federal Reserve System has tremendous, well-earned credibility for understanding and advancing dialogue around the future of our nation’s economic regions. I look forward to continuing to work with the Fed to increase public understanding of concentrated poverty, and to make tackling it a crucial element of strategies to promote regional and national prosperity.

Commentary

Confronting Concentrated Poverty in Tough Economic Times

December 3, 2008