As we begin 2024, U.S. policymakers and Wall Street are reading the tea leaves for signs about the economy’s health. One sector that deserves close attention is the housing market: Strong demand for housing generates additional jobs in related industries, boosts consumer spending, and provides a cushion for homeowners’ portfolios. But for renters, rising housing costs can create financial stress, especially among lower-income households.

This presidential election year offers an opportunity to consider how federal policy could support better housing outcomes for households and communities. Specifically, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)—the main federal agency in charge of housing policy—is not structured, staffed, or funded to address many of today’s challenges.

This piece will outline today’s major housing market challenges and detail HUD’s limited roles in addressing them, before offering innovative approaches the agency can take to engage more holistically in supporting the health of housing markets.

US housing markets face four major challenges

American households, the real estate industry, and policymakers are confronting four urgent challenges stemming from both the supply and demand sides of the housing market.

First, the U.S. is experiencing a persistent and widespread housing shortage. Over the past several decades, housing supply has become less responsive to changes in demand. Growth in population and jobs has not led to proportional growth in the number of homes, while prices and rents have increased faster than household incomes. Researchers estimate a shortage of nearly 4 million homes for the country overall. Some reasons for the supply gap are well understood, such as excessively strict land use regulations that limit new development and a decline in the construction workforce. Other pieces of the puzzle—notably, weak productivity growth in the construction sector—require further study.

Second, the stock of existing homes is aging and in need of substantial renovation or replacement. The median U.S. home is over 40 years old. And like all capital assets, buildings depreciate over time and require ongoing investment to remain safe and habitable. As the number of older adults and people with disabilities increases, there is a growing need to retrofit existing homes with accessibility features, such as no-step entry and grab bars. Meanwhile, many older homes were not built to withstand current and future climate stresses, such as higher-intensity rainfall, sea level rise, extreme heat, and wildfires. The costs of home maintenance are particularly burdensome for low- and moderate-income homeowners.

Third, on the demand side, low-income households cannot afford market rate housing, leading to high rates of housing cost burdens and housing instability. The poorest 20% of households spend more than half their income on housing, leaving too little cash to pay for food, clothes, transportation, and other necessities. In January 2023, more than 650,000 people were experiencing homelessness—the highest number since HUD began its annual point-in-time count, and a 12% increase from 2022.

Finally, the historically unusual combination of high housing prices and high mortgage interest rates is making it difficult for renter households who are trying to purchase their first home. Median home prices have risen nearly 30% from the beginning of 2020 to the third quarter of 2023, while mortgage rates rose from about 3.5% in January 2020 to a peak of around 7.8% in November 2023. Together, these trends mean that households need substantially higher incomes to afford the monthly mortgage payments for a typical home. The decreasing affordability of first-time homeownership is particularly acute for younger adults, because they earn lower wages and have had less time to accumulate savings. Mortgage rates will likely decline over the coming months, but the size and timing of rate changes are uncertain.

These housing challenges are not simply a problem for households who are directly affected—they also create substantial spillover effects across broader communities and regional economies. Building too few homes to accommodate demand—especially in regions with the most productive labor markets—makes it harder for employers to attract and retain workers. Poor-quality housing, high cost burdens, and housing instability are harmful to residents’ physical and mental health, with repercussions for public health systems, worker productivity, and children’s development. And homeownership has traditionally been the primary mechanism for middle-class households to build wealth, so raising barriers to entry can have long-lasting impacts on the financial well-being of families and communities.

HUD’s primary focus—subsidizing poor renters in large cities—is too narrow

In theory, HUD’s mission covers all four of the housing challenges outlined above. Per the agency’s website:

“HUD’s mission is to create strong, sustainable, inclusive communities and quality affordable homes for all. HUD is working to strengthen the housing market to bolster the economy and protect consumers; meet the need for quality affordable rental homes; utilize housing as a platform for improving quality of life; build inclusive and sustainable communities free from discrimination, and transform the way HUD does business.”

But in practice, most of HUD’s budget and staff resources are directed toward supporting low-income renter households through a combination of subsidy programs, shown in Table 1. Tenant-based rental assistance, or housing vouchers, are by far the largest single budget item, followed by project-based rental assistance and public housing.

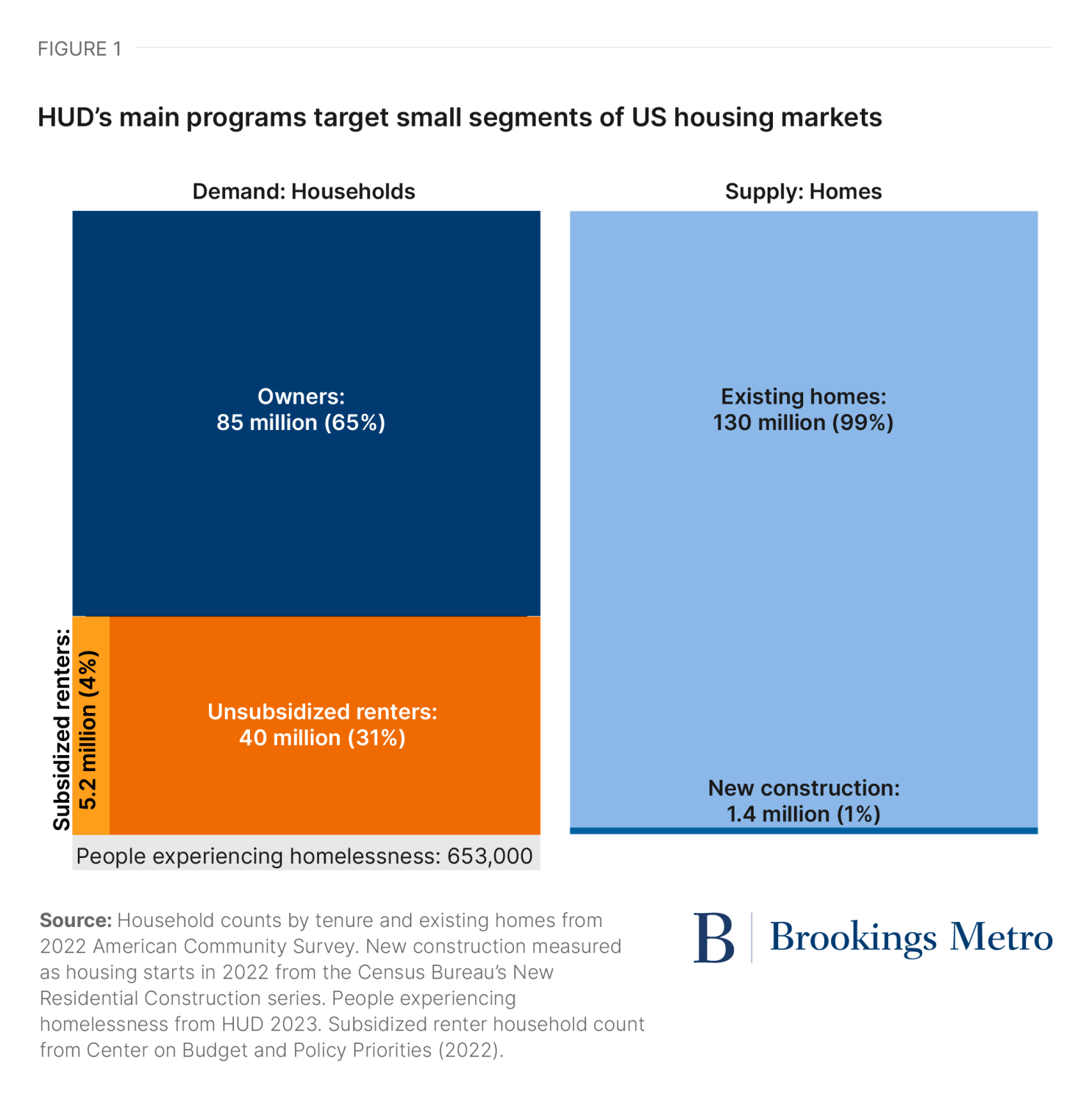

To provide context for HUD’s scope within broader U.S. housing markets, Figure 1 visualizes housing demand broken out by tenure and housing supply segmented in existing homes and new construction.

Renter households receiving federal subsidies constitute about 4% of all U.S. households. Even among low-income renters, three-quarters of households receive no federal housing subsidy. This reflects the fact that housing assistance—unlike food stamps and Medicaid—is not an entitlement, but subject to annual budget appropriations from Congress.

The largest segment of demand that HUD engages does not show up in the budget numbers: The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) is an important source of lending for first-time homebuyers. The FHA insures mortgages for moderate-income homeowners, and its loans are securitized by the Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA). In 2022, approximately 800,000 first-time homebuyers purchased homes with FHA-backed loans. The FHA’s share of the overall home purchase loan market is considerably smaller than the government-sponsored enterprises, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, but is more targeted toward first-time buyers—especially households with lower incomes and lower credit scores. GNMA also securitizes mortgages from two other federal agencies that provide loans to moderate-income homeowners: the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Agriculture’s Rural Housing Service.

HUD’s programs represent an even smaller footprint on housing supply. Since the 1980s, nearly all new construction of affordable housing has been financed through the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program, which is administered through the Treasury Department. HUD has little direct role in the LIHTC program, although many LIHTC residents also receive tenant-based vouchers. The existing stock of traditional public housing and other project-based subsidies represents less than 1% of all homes—a much lower share than in other wealthy countries. The 2024 budget does include a few small programs aimed at housing production, including $85 million for a new competitive grant program encouraging local zoning reforms. And some block grant programs to local and state governments can be used for the renovation of existing affordable housing projects, including apartment buildings owned by nonprofit or for-profit providers.

HUD’s narrow scope has both practical and political downsides

Supporting economically and socially vulnerable families who are not well served by private, for-profit housing providers is an important policy goal. But this narrow purview limits HUD’s relevance for the vast majority of U.S. households—with both practical and political consequences.

The broader structural problems with housing markets hinder HUD’s ability to improve housing affordability and stability for low-income renters. Zoning rules that prohibit development of market rate apartments also prohibit LIHTC projects and other subsidized apartments. Tight rental markets due to limited supply make it harder for households who receive vouchers to find an available apartment. The per-household cost of vouchers rises along with rent levels. And when rising prices and high mortgage rates limit renter households from purchasing their first homes, pressure increases on rental markets—squeezing low-income renters even more.

Historically, HUD has focused mostly on big cities—a legacy of previous federal efforts such as urban renewal. Even today, the location of HUD-assisted households skews toward cities: 50% of federally assisted renters live in urban areas, 34% in suburbs, and 16% in rural areas. Among all U.S. households, slightly over one-quarter live in urban areas, more than half live in suburbs, and the remaining 20% in rural areas. Some of the difference in geographic distribution reflects population characteristics, such as income and tenure. And some of HUD’s subsidy programs—including housing vouchers and the Community Development Block Grant program—are designed around big city governments as the primary administrative entities.

As a result, HUD has limited experience engaging directly with smaller cities and counties (including smaller suburbs within metro areas), and has almost no relationships with state governments. Yet small communities, which have limited housing and planning staff, would benefit from guidance and technical assistance on new policy initiatives. Further, over the last several years, state governments are increasingly engaging with policies to encourage housing production—a conversation that has largely excluded HUD.

Politically, cultivating support among voters and members of Congress might be easier if HUD’s work visibly benefited a broader base of American households.

Think outside the budget: Low-cost, flexible, collaborative approaches

An obvious reason why HUD’s current focus is mostly on supporting low-income renters is that Congress (past and present) has appropriated funds specifically for rental subsidies. HUD, and the federal government more broadly, have limited direct authority over housing production and renovation. Rather, state and local governments are responsible for writing and enforcing zoning laws, building codes, and other policies that govern housing development and maintenance. Mortgage interest rates fluctuate with monetary policy set by the Federal Reserve System, while loan terms and underwriting reflect decisions by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, under the supervision of the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

These fundamental limits on HUD’s policy toolkit are unlikely to change. Even if HUD wanted to create an “Office of Housing Production,” it could not override local zoning. And there is little appetite in either party to finance large-scale construction of social housing along the lines of Vienna or Singapore.

But even within these constraints, the agency could play a more proactive role in monitoring the health of housing markets, developing and testing innovative policy ideas, coordinating research and data collection, and supporting state and local governments. (Research makes up less than 1% of HUD’s current budget.) The recommendations below are not solutions to specific policy problems, but rather a set of flexible tools that could be applied to a range of issues—and potentially win bipartisan support.

Hire leadership and staff with expertise beyond the subsidized housing industry

HUD’s senior leadership tends to be drawn mostly from the affordable housing industry, such as local public housing authorities or entities engaged with LIHTC development. The agency could encourage more innovative thinking by adding leadership and staff with complementary expertise, such as private sector developers and property managers, real estate finance experts, housing market analysts, and local or state officials who have managed successful zoning reforms.

Conduct, coordinate, and disseminate research and development

Behind the major housing challenges are a number of unanswered questions that would benefit from well-targeted research efforts. Commissioning, funding, and coordinating researchers across universities, think tanks, industry, and practitioners falls squarely within HUD’s jurisdiction. Among the key questions are:

- What explains declining productivity in housing construction?

- How effective are recent state and local zoning reform efforts? What policies work best in which types of housing markets?

- What are the most cost-effective strategies to retrofit existing homes and neighborhoods for energy efficiency and climate resilience?

- How effective are local affordable housing programs such as inclusionary zoning, rent stabilization, and different homelessness reduction strategies?

Leverage relationships with other federal agencies and the real estate industry to monitor real-time data

Better data on the health of U.S. housing markets is critical to developing appropriate policy interventions. The federal government publishes an extensive set of monthly indicators on labor market conditions: employment counts from multiple sources, wages, and job listings. Housing market indicators have tended to focus more on aggregate supply measures than household well-being (with the notable exception of the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey). Much of the best real-time information—especially on rental markets—comes from private sector sources. HUD should play an essential role in assembling housing market metrics across all these sources and sharing updates with key stakeholders.

Encourage regional collaboration among housing authorities to preserve and expand affordable housing

Most of HUD’s programs now focus on housing authorities or agencies within a single political jurisdiction, contributing to fragmented efforts to address affordability. However, waivers of existing rules in program such as the Rental Assistance Demonstration and Moving to Work can foster consortia-based solutions and encourage collaboration across multiple public housing authorities, nonprofit and private property owners, and essential service providers.

Build up triage and rapid response capacity

Over the past 15 years, two different crises have roiled housing markets: the foreclosure crisis of 2007 to 2009 and rental instability caused by COVID-19. In both instances, HUD was pushed into reacting after the crisis occurred, without having contingency plans in place (to be fair, not a problem unique to HUD). To be better prepared for the next housing crisis, HUD should build a small in-house team that monitors signs of impending distress, in coordination with other relevant agencies.

We need a bold vision to solve today’s housing challenges

The housing challenges facing Americans today are not going to solve themselves. The persistent shortage of homes, depreciating housing quality, and acute affordability problems require HUD’s leadership to boldly go where affordable housing policymakers have not gone before. Playing it safe and staying within traditional comfort zones is no longer good enough.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

To meet today’s critical housing challenges, HUD needs a broader, bolder vision

January 22, 2024