MEDIA SUMMARY

Central banks failing at shaping public expectations of monetary policy

Inflation expectations are poorly anchored, but policymakers should not give up trying to communicate

In spite of a quarter century’s worth of central bank efforts to communicate inflation targets and shape public expectations, firms are no better than the general public in estimating inflation and often fail to incorporate recent inflation data into their business decisions.

Central bankers have increasingly emphasized the importance of the public’s expectations, given that unanchored inflation expectations are commonly believed to have helped cause the spiraling inflation in the 1970s and the subsequent large costs of bringing down that inflation over the following decade.

In “Inflation Targeting Does Not Anchor Inflation Expectations: Evidence from Firms in New Zealand,” Saten Kumar of Auckland University of Technology, Hassan Afrouzi and Olivier Coibion of University of Texas at Austin, and Yuriy Gorodnichenko of University of California at Berkeley review the results of a series of surveys conducted on New Zealand firms between 2013-2015, and draw connections between New Zealand and the U.S.

They find that company managers have been forecasting much higher levels of inflation than has actually occurred, at short-run as well as very long-run horizons. “Firms also express far more uncertainty in their inflation forecasts than do professional forecasters. In fact, along almost every single one of these metrics, the managers of firms resemble households in New Zealand much more than they do professional forecasters,” they write.

The authors find that respondents in both countries are generally ignorant of the operations of their own central bank, with only about one in every three American and New Zealanders correctly identifying the heads of their central banks when presented with a list of four names.

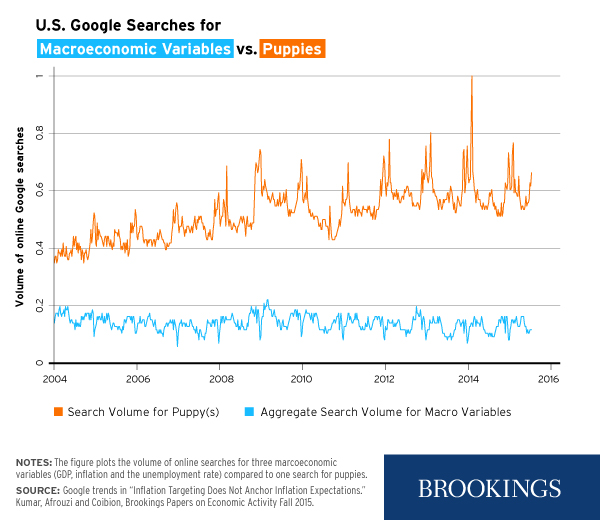

“Google searches confirm this paucity of interest [in monetary policy],” they write. “Online searches for macroeconomic variables like GDP, unemployment rate and inflation are consistently topped altogether by online searches for puppies.”

“Maintaining low and stable ‘well-anchored’ inflation expectations has become a mantra of modern central banking. But with the onset of the zero bound on interest rates, expectations have also taken a new role as a potential instrument of monetary policy. By trying to raise inflation expectations when they are very low, central bankers can immediately lower real interest rates and thereby stimulate economic activity even when nominal rates are constrained, a strategy actively pursued by the Central Bank of Japan, for example.”

The authors consider five measures of anchored inflation expectations: (1) proximity of average beliefs to the inflation target; (2) concentration of beliefs around the inflation target; (3) confidence in forecasting; (4) small revisions to forecasts, especially at longer horizons; and (5) little correlation between short- and long-run inflation expectations. Their results for both the U.S. and New Zealand are discouraging – the firms in their survey consistently fail on all five counts. Results are similar for households in the U.S.

The authors consider five measures of anchored inflation expectations: (1) proximity of average beliefs to the inflation target; (2) concentration of beliefs around the inflation target; (3) confidence in forecasting; (4) small revisions to forecasts, especially at longer horizons; and (5) little correlation between short- and long-run inflation expectations. Their results for both the U.S. and New Zealand are discouraging – the firms in their survey consistently fail on all five counts. Results are similar for households in the U.S.

Despite these results, the authors suggest policymakers could have an impact with their shaping of expectations. When firms without a strong understanding of the central bank’s objective were given information, nearly all managers reported some sensitivity to inflation expectations and they often made significant revisions to their inflation forecasts. Thus, even though inflation expectations are poorly anchored, they are not irrelevant to business decisions, the research shows. The authors also suggest that credibility is not a major problem – at least in New Zealand – and report that those survey respondents who could correctly answer three basic questions about the Reserve Bank of New Zealand also produced better-informed inflation forecasts, and displayed a better understanding of recent inflation dynamics.

If central banks can communicate more effectively with the public – a mission they note the Federal Reserve in particular has struggled with – and in so doing alter firms’ and individuals’ inflation expectations, “then there will be indeed be [positive] economic repercussions.”