Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in The Wall Street Journal

We’re going to hear a lot from 2016 presidential candidates about the need for faster economic growth. Jeb Bush says annual growth of 4% would be his goal; that’s almost double the 2.2% U.S. growth rate since June 2009. Hillary Clinton has called for “inclusive” growth, or economic expansion that is distributed more fairly. (I suspect that many Republicans agree with her objective, while differing on what government should do to achieve it.)

Presidential elections are occasions for debating government’s role, so it’s natural to focus on things government can do to affect economic growth, such as simplifying the corporate tax code, removing distortions, and, for some, lowering rates; investing more in infrastructure and early-childhood education; and easing regulatory burdens, especially for new businesses, which have been the source of many major technological advances.

While some or all of these things should help growth, government has limited ability to influence the appetite for taking risks among entrepreneurs, investors, and larger companies. And without risk-taking, we are unlikely to see the kinds of major new innovations that will propel our economy toward a higher growth trajectory.

Two recent essays define this challenge. One is a thoughtful piece by Bloomberg View’s Barry Ritholtz on the decline in publicly traded companies in the U.S., from a peak of more than 7,300 in 1996 to just 3,700 in 2014. After surveying multiple possible causes for the nearly 50% decline–including the much-criticized Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which tightened public company reporting rules–Mr. Ritholtz cites academic research showing that mergers have played an outsize role in reducing the number of public companies.

This is important because when big companies swallow up others, it signals that acquiring companies have essentially outsourced their ideas rather than growing internally. It also suggests that the safer thing to do is to buy someone else rather than develop new products and services yourself. The merger trend is a sign of a collective failure of nerve, the risk-taking that historically contributed to much higher economic growth rates, such as the roughly 4% average from 1948 to 1973.

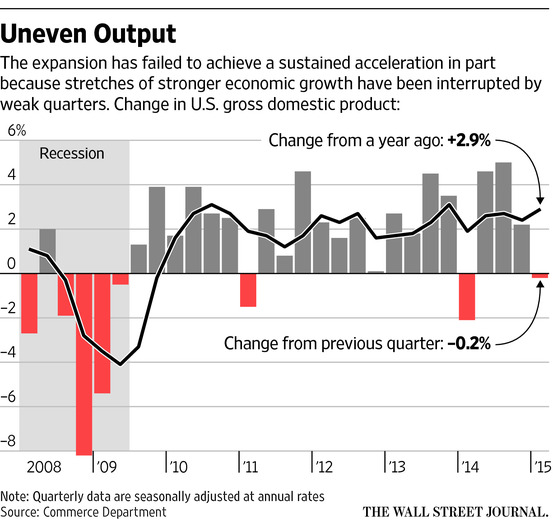

The other piece is an essay by Fortune editor Alan Murray summarizing the results of the latest Fortune 500 rankings. He reports that revenues of the Fortune 500 companies combined equal 71.9% of U.S. gross domestic product, or more than twice the 35% it totaled in 1955. In other words, despite continuing turnover in the Fortune 500′s composition, big companies are more important than ever as a share of the overall economy. And Mr. Ritholtz’s results help explain why: Big companies are getting bigger largely through mergers (though neither he nor Fortune calculates to what extent).

This wouldn’t be so worrisome for future growth were it not for the decline in the start-up rate, or share of new companies in the number of overall firms, which I have written about before. Despite the continuing emergence of new billion-dollar start-ups (“Unicorns”), the execs of big companies don’t appear to be especially worried. According to the Fortune survey, only 20% think their greatest challenges will come from start-ups.

At the top of their worry list, Fortune found, is the “rapid pace of technological change,” which is ironic since, so far, hype has exceeded reality. As Princeton professor Alan Blinder has noted, productivity growth since 2010 has clocked in at just 0.4% a year, down from 2.6% over the preceding 15 years.

So presidential aspirants are right to encourage faster and more inclusive growth. But unless a big boost in start-ups puts real pressure on large companies, the answer to the growth challenge lies mostly with large companies and those who head them.

Commentary

Among ingredients needed for faster growth? Greater appetite for risk.

July 8, 2015