The announcement that the Senate will not take up broader climate change legislation before the August recess makes it likely that Congress will not vote to curtail carbon emissions through a cap-and-trade system this year.

This seems like a natural time to explore what we will lose by failing to implement an economy wide domestic cap-and-trade system.

Using new analytic tools, we can calculate the actual costs of continued inaction on climate change and the potential benefits of implementing new cap-and-trade policies. The findings of this exercise are surprising: the benefits to the United States economy of a cap-and-trade system exceed its costs.

The U.S. government recently examined the full range of scientific and economic data and developed a new way to measure the costs of releasing greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide, into the atmosphere. The government’s central conclusion (pdf) is that the release of an additional ton of carbon dioxide today will cause about $21 of damage globally. This is referred to as the social cost of carbon. It finally puts a monetary value on the expected damages from climate change, including shortened life spans, reduced agricultural yields, and increased property damage due to higher sea levels.

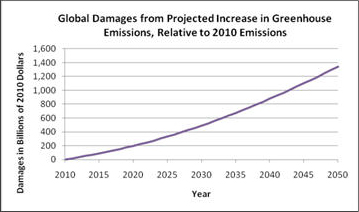

The social cost of carbon confirms that the price of inaction is substantial. Assuming that all nations continue on their current emissions path, the average annual damages from the increase in greenhouse gas emissions, relative to 2010 emissions, is expected to be about $100 billion over the next decade. As the chart reveals, the annual damages by 2050 would be equal to nearly $1.3 trillion. If caps are not put in place, the average annual damages from greenhouse gas emissions would be about $570 billion over the next four decades.

<not-mobile message=”To see the chart, please visit Brookings.edu on your desktop.”> </not-mobile>

</not-mobile>

The projected economic damages for the United States alone are estimated to reach $200 billion annually by 2050. Over the next four decades, the average annual damages are projected at $85 billion.

There is significant momentum for regulations and subsidies to boost the energy efficiency of buildings and cars and incentives for nuclear energy and renewable energy sources. These types of policies tend to be expensive approaches to reducing greenhouse gasses and are unlikely to reduce emissions by enough to substantially slow climate change.

An economy wide cap-and-trade system that limits carbon emissions, or the levying of a fee for carbon emissions, would harness market forces to find the least cost means to reduce carbon emissions. The Hamilton Project, an economic policy group that I now direct, detailed the importance of this approach in 2007. Furthermore, the social cost of carbon calculation illustrates this point by allowing us to examine the impact that different climate policies will have within a cost-benefit framework.

I assessed the benefits and costs of the cap-and-trade programs that have been considered in Congress. Specifically, I examined the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) recent analysis of the economy wide cap-and-trade provisions of the American Power Act legislation, which the Senate considered. Using the social cost of carbon, the global cumulative benefits of the emissions reductions produced by the legislation is roughly $1.5 to 1.7 trillion between now and 2050. In comparison, the EPA’s analysis indicates projected cumulative domestic costs of $600 billion to $1 trillion over the same period.

Of course, it is natural to ask why Americans should pay for benefits in other countries. Climate change is a global problem and, as such, some of the benefits from U.S. action will spill over to other countries. In the same vein, we will also reap the benefits from carbon reduction programs abroad. What we have learned through past negotiations in the international arena is that if the United States takes a clear leadership position, it will greatly increase the chances of a global agreement to reduce emissions.

The passage of an economy wide cap-and-trade system would exert just such leadership. Indeed, the real payoff from a domestic cap-and-trade system is that it could pave the way for global action toward emission reductions along the lines that were discussed at the Copenhagen climate change summit in December. If there are global emissions reductions like those spelled out in the Copenhagen Accord, then the domestic benefits would easily exceed the domestic costs.

The critics of cap-and-trade have been correct all along. It would impose costs on the U.S. economy. What they have failed to notice, however, is that the projected benefits are larger than these costs.

Commentary

The Benefits of Cap-and-Trade Would Have Exceeded Its Costs

July 30, 2010