This is the epilogue to a six-part series on federal disaster policy reforms published in summer 2023. Previous posts outlined principles for reform, examined changes to the declaration process, recommended improvements in the federal disaster management system, explored the division of responsibilities between federal and state governments and the private sector, suggested how to build the capacity of under-resourced local governments, and highlighted ways to help our most vulnerable neighbors better prepare for and recover from disasters.

When our team conceived of this disaster policy reform series, we thought broadly across the institutions that prevent our current system of disaster laws, rules, and practices from being as equitable, efficient, effective, and environmentally responsive as possible. As we wrote the series last year, we pulled lessons from our own empirical research and that of our colleagues, as well as our interactions with public officials and civil society in these areas—all in the hope of identifying the broad brushstrokes needed on the arc toward reform.

Such calls for disaster policy reforms are mounting from multiple corners, fueled especially by the frequency and growing effects of the disasters themselves. We did not anticipate that our series—along with similar calls—would be quickly integrated into college curricula, cited widely in the news media, and be referenced by policymakers and activists. Our proposals build on years of past research and intensive debate, and we expect several more years of analysis and advocacy. But we were elated to see the pace and quantity of changes in program rules and practices that have occurred over the last year within federal disaster agencies as we developed our proposals. Indeed, all manner of practical reforms and administrative changes have taken place since we put down our pens last fall.

Most notably, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) announced major updates to the Individual Assistance (IA) program, which are going into effect this month. But there have also been important administrative and management improvements across the broader ecosystem of post-disaster programs. FEMA’s hazard mitigation programs have also prioritized underserved communities in their competition selections. The range of federal efforts include ongoing calls for public feedback, the elevation of agency recovery activities, and flexible local resources for highly vulnerable populations, such as those experiencing homelessness.

In some cases, federal reform efforts have faced pushback from industry and special interests, and have had to adapt. For example, the Treasury Department stepped back from its earlier call for gathering information on homeowners’ insurance, instead letting the National Association of Insurance Commissioners lead on data gathering. Yet overall, meaningful change is happening, and we are pleased to find that it has been aligned with the major reform principles that we set out in our series (see Figure 1).

Three key changes in FEMA’s IA operations are especially noteworthy and aligned with our proposals. First, the move to establish the Serious Needs Assistance (SNA) program mirrors our suggestion to move as much assistance to the most economically vulnerable survivors as early after a disaster and with as few strings as possible. Specifically, we recommended providing immediate, modest disbursals of aid to all occupants at or below 80% of the median area income simultaneous to the declaration, regardless of damages and without the submission of a formal request for aid. By having upfront payments clear to all parties before the disaster, families would also know that they could pay for immediate relief needs and plan for their recovery earlier. SNA provides cash relief of $750 to a segment of this population based on their unique circumstances.

Second, FEMA’s changes to the repairs that are eligible for IA are also an important reform that more equitably expands its assistance distribution. Previously, any pre-existing conditions—such as structural holes or system disrepair, which are typically signs of housing inadequacy—would not be eligible for repair with IA funds. Now, survivors in these homes can include these repairs regardless of whether the specific disaster that opens IA to them caused those damages. In addition, they can use FEMA dollars for investments to any part of the home that lowers losses from future disasters. Coupled with allowing accessibility improvements for survivors with disabilities to be covered by IA and the flexibility in damage assessments, the expansion of home improvements FEMA covers not only ensures that the most vulnerable households can live in higher-quality housing, but also that their housing is more resilient and better prepared for the next disaster.

The third important change is FEMA’s approach to providing IA as a supplement for underinsured damages rather than as a substitute for insurance claims. Previously, insurance payments would be subtracted from eligible assistance. Now, IA assistance can cover costs not reimbursed by insurance, up to the federal cap (currently at $42,500). While there might be concern that this change could create a perverse incentive to underinsure, for households that struggle with ever-increasing insurance costs, the ability to use FEMA dollars to cover below-deductible expenses and uninsured losses will be welcome relief. As FEMA adopts these changes—which went into effect on March 22—there should be robust learning and evaluation to understand potential incentive effects and other unintended impacts.

These and the other changes federal agencies made under executive action from the Biden administration are laudable and will make it easier on disaster survivors, particularly the most disadvantaged. These are critical improvements each agency was able to make within current law and within its own mission, staff, and culture. But deeper reforms will require tradeoffs across the principles our series articulated, and federal agencies are not in the best position to navigate those tradeoffs since their programs are, by design and legislative intent, constrained by statute. In some important cases, such as the Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program, the programs are not even permanently authorized—they require congressional action after each disaster season, which prevents agencies from making significant structural changes to them.

To initiate a comprehensive set of reforms, many of the statutory limitations for agencies and their disaster-related programs need to change as well. This requires legislation. The disaster-related agencies, their programs, and the programs’ parameters (not to mention their budgets) have been subject to legislation going back a half-century.

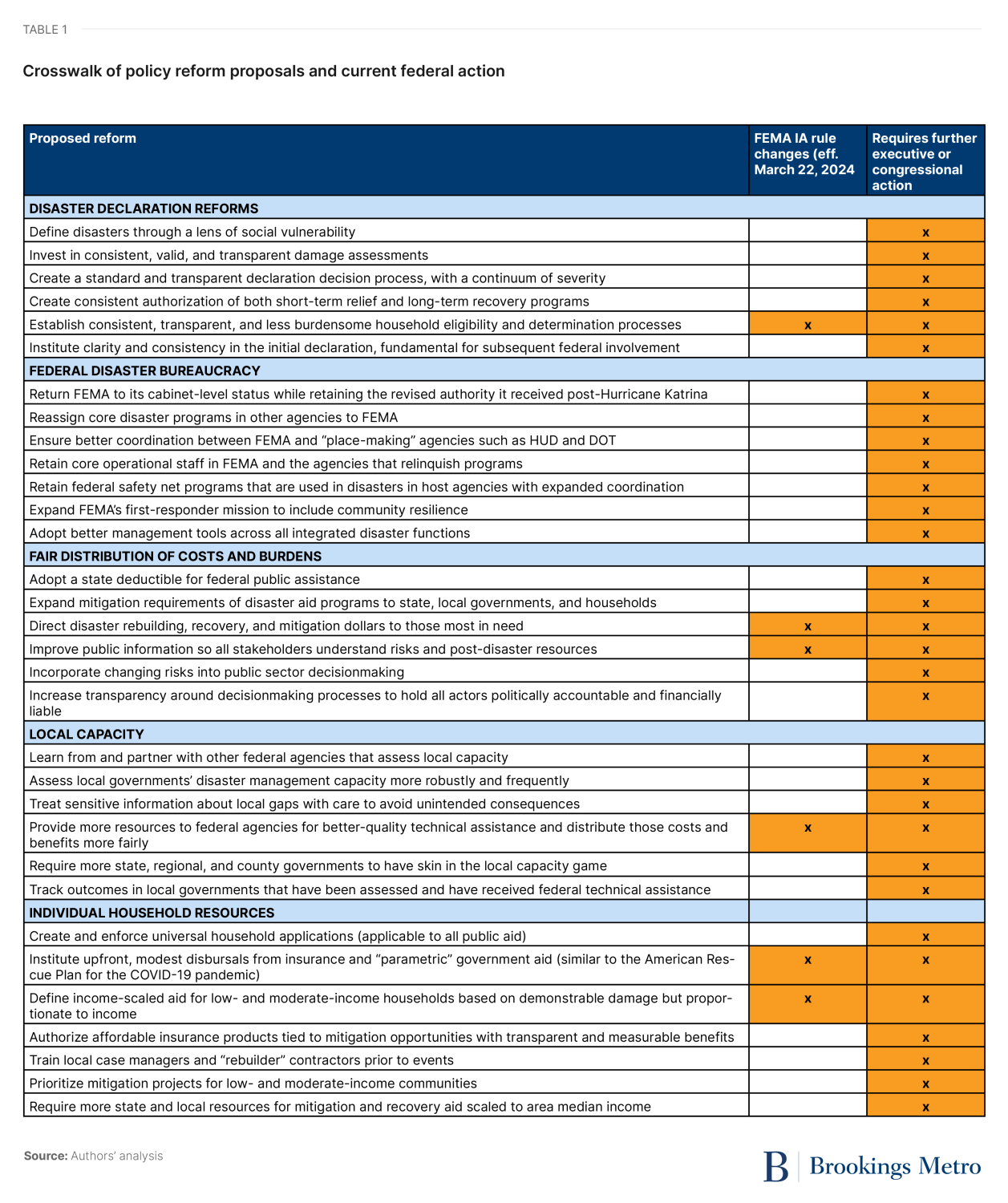

A collective reform movement today must involve an all-of-government approach that includes not just every executive agency in the federal government and state governments referenced in the series, but the legislative branch too. Though FEMA’s revised rules and practical changes certainly move the ball forward on many counts, there are still significant gaps—and, as such, big opportunities for improvement—when we compare those administrative reforms to the range of our policy proposals (see Table 1).

Numerous groups and individuals have called for major legislative changes across the range of these proposals and their respective touch points for households and communities. In many instances, Congress is listening. Over the last several sessions, both sides of the aisle have introduced weekly proposals for both tweaks and fundamental changes, much of them with bipartisan support. In response to a request for comment on our policy proposals, we received the following video from Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Calif.):

In addition to finding gaps in programs and policies during our research, we undertook this project with the knowledge that our disaster policy is also currently our nation’s de facto climate adaptation policy. And so, any reforms would need to be durable and capable of withstanding the range of climate-related hazard events and transition risks that we will witness on U.S. soil over the next several decades.

When we consider the fact that last year saw the highest number of billion-dollar-plus disasters in U.S. history—a whopping 28 disasters of that magnitude among the 71 major disaster declarations—the call for disaster policy reform becomes even more urgent. And the outlook remains sobering, to say the least. For example, the latest scientific analyses forecast another “extremely active” hurricane season, due in part to a warming ocean. Still, the encouraging progress on practical reforms over the past year makes us hopeful that a whole-of-government response will leave us better prepared and equipped for the disasters to come.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

This series was made possible through funding by the Walmart Foundation. The findings, conclusions, and recommendations presented in this report are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Walmart Foundation. The authors are grateful to the Brookings Institution and Brookings Metro staff for providing a platform to share our thoughts about disaster policy reform, and to Representative Waters and her staff for considering our proposals

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).