At the third round of Democratic debates this week, moderators should ask candidates their position on a serious kitchen table issue: the increasing difficulty many Americans face in paying their monthly rent or mortgage. On the campaign trail, candidates are talking more about housing than in any other presidential election in recent history. The renewed attention reflects both economic realities and political ones.

Over the past 20 years, housing costs as a share of income have increased for middle- and low-income Americans, putting more financial pressure on families. Affordability problems are particularly acute for younger, non-white households living in large urban areas—key Democratic constituencies. The 10 candidates appearing on the debate stage this week offer several different approaches to relieving housing stress. In this blog post, I set out a set of criteria to help voters evaluate candidates’ housing policy proposals.

What makes a good housing plan? Having one, to start with.

At this stage in the campaign, details of the candidates’ housing proposals are less important than whether they are correctly identifying critical problems and the underlying causes. (Proposals are largely meant to signal candidates’ priorities and their general approach to issues; turning proposals into law requires legislative approval under a hypothetical newly elected Congress.)

Not all candidates have explicitly talked about housing, and proposals vary widely in scope. To date, five candidates have thorough, detailed proposals on their campaign websites: Cory Booker, Julián Castro, Kamala Harris (here and here), Amy Klobuchar, and Elizabeth Warren. Pete Buttigieg’s Douglass Plan addresses housing, among other issues. Bernie Sanders has discussed housing in op-eds and a town hall meeting. The remaining candidates in Thursday’s debate lineup—Joe Biden, Beto O’Rourke, and Andrew Yang—have either spoken about housing in relation to other policies or released few details.

Candidates should highlight the most important problems: affordability, supply, and racial disparities.

Housing policy—like most other policy areas—is complicated. The types of housing stress renters and homeowners experience vary based on factors such as geography, income, age, and race. Not every candidate needs to have a detailed plan to unwind conservatorship of the GSEs, for instance. But there are three issues that any credible proposal should address.

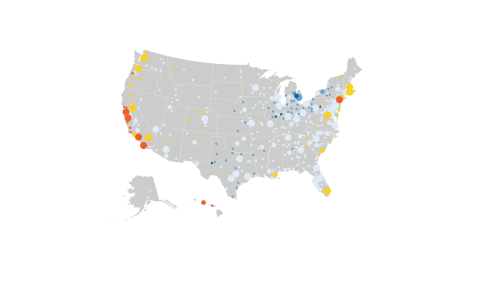

The most critical problem is the gap between incomes and housing costs for poor families. Having stable, decent housing in a safe and healthy community is the foundation for all other economic and social activities. Yet the poorest 20% of families in all parts of the U.S. cannot afford housing without cutting back on food, health care, or other necessities. These families earn too little income to cover the rent on minimum-quality apartments without some subsidy from the government. And the challenge for poor families has gotten worse over the past few decades, as the share of eligible households receiving federal housing assistance has declined.

The most critical problem is the gap between incomes and housing costs for poor families. Having stable, decent housing in a safe and healthy community is the foundation for all other economic and social activities.

The second major problem is that, in many communities with strong labor markets and excellent amenities, housing supply has not kept pace with population and job growth. Increasingly strict local government regulations, such as large minimum lot sizes and bans on apartments, have driven up housing prices. Procedural rules have made housing development more complicated and risky, and given existing residents (NIMBYs) too much power to block new construction, especially in the most desirable locations. Tackling high housing costs in coastal metros will require building more housing, more quickly and cheaply—and a substantial reform of local zoning regulations.

Third, the federal government needs to address persistent racial disparities in housing caused by discriminatory public policies. Black households today have lower homeownership rates and overall wealth than white households due to historic redlining—the federal government’s practice of systematically denying mortgages to black applicants and black neighborhoods. The same local zoning rules that restrict housing supply also reinforce racial and economic segregation.

Four candidates—Booker, Castro, Klobuchar, and Warren—have proposed credible approaches to address all three major issues. They differ somewhat in specific mechanisms, but all are reasonable starting points. Harris and Sanders have conspicuously avoided any discussion of the need to build more homes—a particularly striking omission from Harris, whose home state is ground zero for zoning battles. The remaining candidates have not provided enough detail to indicate how they would approach housing in office.

Complex housing problems don’t have one correct solution. Misdiagnosing the issues won’t help.

None of these problems will be easy to solve. All are the result of complex market forces interacting with layers of government policies over many decades. Well-informed and well-intentioned candidates can reach different conclusions on what policy changes would be most effective. For instance, housing affordability for low-income households could be helped by expanding HUD’s housing voucher program, or by supplementing incomes through tax credits or a higher minimum wage. Housing experts have different opinions on how—or whether—the federal government should incentivize local governments to reform their zoning policies.

While candidates can and should have a robust debate about solutions, it is critical that they demonstrate a solid understanding of how housing markets work.

While candidates can and should have a robust debate about solutions, it is critical that they demonstrate a solid understanding of how housing markets work. Candidates who misdiagnose the problems or the underlying causes may cause more harm than good. Proposals to give households more money without addressing supply constraints could make housing affordability worse in high-cost metro areas. Candidates who call for building more federally subsidized housing may be unpleasantly surprised to learn that zoning bans on apartments apply to subsidized as well as market-rate homes.

Making progress towards any these goals will require some politically unpopular choices. Any candidate who promises a magic wand that can fix housing problems without costing taxpayers more money or annoying middle-class homeowners is not being honest with voters—or themselves.

Commentary

Campaign 2020: How to fix America’s housing policies

September 10, 2019