Rather than count on continued good luck of North Korea not delivering a gift, Washington should propose an interim deal to serve the vested interests of each nation, writes Michael O’Hanlon. This piece originally appeared in The Hill.

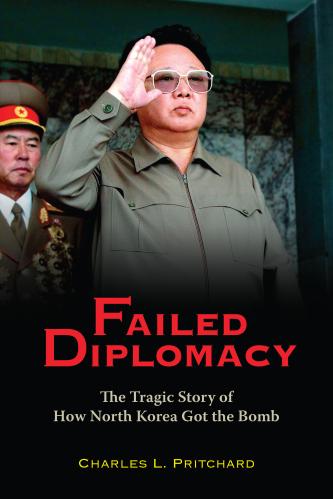

The Christmas season is halfway over with no sign of the gift that was promised for the United States by Kim Jong Un, the brutal and cunning young North Korean leader, after a prolonged period of paralysis in talks over his nuclear weapons program. But rather than count on continued good luck of North Korea not delivering the gift, Washington should propose an interim deal to serve the vested interests of each nation.

Largely as a result of the sanctions imposed after North Korean nuclear and missile tests three years ago, the North Korean economy remains in recession, with estimates by the South Korean central bank showing annual contractions of up to 4 percent a year. That is despite imperfect enforcement of sanctions by the likes of China and Russia. Earlier this year, President Trump rightly walked out of his second summit with Kim, when the dictator had demanded a complete lifting of sanctions in return for a shutdown of the main North Korean nuclear production site but no surrender of any nuclear warheads, which could number in the dozens.

Trump and Kim have maintained a veneer of personal warmth since then, and met one more time briefly near the demilitarized zone in the spring, but official talks have gone nowhere. Trump touts his overall diplomacy towards Kim as a major success. While it is true that the moratorium of two years on North Korean nuclear and long range missile tests counts for something, it is hard to sustain that argument as other missile tests take place, and as the North Korean nuclear arsenal almost certainly continues to grow. Much worse could be in store, such as a nuclear test, or another intercontinental ballistic missile launch perhaps in the guise of putting a satellite in orbit, or even a lethal attack against innocent South Koreans.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration seems unsure how to proceed. Even after John Bolton departed as national security adviser, hardline factions insist on complete, irreversible, verifiable, and fast nuclear disarmament. This means the elimination of North Korean warheads and infrastructure used to make more of them. Only then would sanctions be lifted. Trump has claimed that the United States would then help North Korea build a modern economy, but such an objective is an extreme longshot at best.

If Kim harbors concern of Trump authorizing a military attack because of a breakdown in talks, he likely fears even more a world in which he faces the United States and South Korea without having the bomb. Scholars such as Jonathan Pollack and Jung Pak have also documented the importance of the North Korean nuclear program toward the entire Kim dynasty. These warheads are quite literally the crown jewels of the North Korean regime. The young Kim would betray his family legacy by giving them up lightly.

Other factions in the Trump administration seem more pragmatic about how to envision a deal. Deputy Secretary of State Stephen Biegun said, “North Korea need not do everything before we do anything.” But the specifics of such a more flexible approach have not been evident. As a new year dawns, it is time for Washington to decide on a strategy. This puts Trump in a tough spot. No president has ever thought it acceptable to recognize North Korean nuclear capabilities and rightly so. Trump and his constant railing against the Iran deal also makes it difficult to brag about any deal with Kim that falls short of complete denuclearization.

Yet there is still a logical path. The United States, along with South Korea and other nations, should agree to suspend then lift most United Nations sanctions that severely crimp North Korean trade. These sanctions, more than any other measures besides North Korean mismanagement of its economy, have done the real damage. Sanctions relief should occur if, and only if, North Korea verifiably dismantles the entirety of its nuclear production infrastructure, after submitting a declaration or database on those facilities to check against official American intelligence estimates.

Such a deal would permanently cap the North Korean nuclear arsenal at its current size. The accord should also make the testing moratoria official and permanent. This measure would cap the quality and sophistication of North Korean long range missiles as well. North Korea could keep most of its warheads for now, and the United States, to retain leverage for future negotiations some day, would keep its own American sanctions in place.

Most American trade and aid for World Bank and International Monetary Fund support would be withheld and so, presumably, would Japanese and European Union support. Whether a second agreement that achieved true disarmament happened anytime soon or not, the parameters of such an accord would achieve critical limits on North Korean nuclear and missile capabilities that no previous president has managed to establish. A low key declaration of an end to the formal state of war that has been on the peninsula since the 1950s, and opening liaison offices between the two Koreas and the United States, could also be part of the understanding.

With such a deal, the world could breathe a huge sigh of relief as the threat of war would recede further. Outside powers then could seek to gradually wean North Korea away from those remaining aspects of its Stalinist system, as was done with Vietnam over the years. This kind of interim agreement might not be conclusive enough to warrant a Nobel Prize, but it substantially lower the risks of war and of nuclear danger.

Commentary

Why America should strike an interim deal with North Korea

January 2, 2020