The December employment numbers, released today by the U.S. Department of Labor, show signs of improvement in the labor market. The economy added 103,000 jobs last month—although encouraging after last month’s disappointing growth, this is not large enough to absorb new entrants and make a dent in the “job gap,” explained in further detail below. However, unemployment fell to 9.4 percent.

December 31st marked the end of a decade, and the three year anniversary from the start of the Great Recession. In this month’s posting The Hamilton Project takes a step back, offering a retrospective look at trends in income and the labor market that the U.S. economy experienced over the last decade. In brief, we begin 2011 with much room to grow, as too many American workers continue to face unemployment and average wages remain largely unchanged from the beginning of the last decade.

Employment is down, Income is Flat

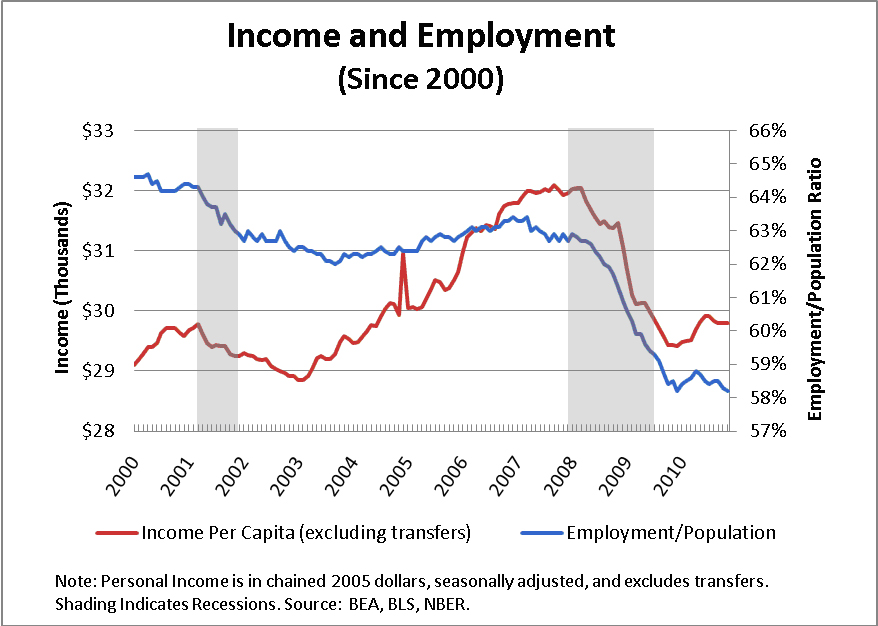

Workers suffered the sharp pangs of a sinking economy in the first decade of the 21st century. Since 2000, we have experienced two severe recessions that battered the incomes of and employment opportunities for American workers (the recession of March 2001-November 2001 and the Great Recession of December 2007-June 2009). The effect of these recessions is shown in the chart below:

Income per capita (excluding transfer payments like Social Security and unemployment benefits), rose over $3,000 per person from 2003-2008. But these gains were undone by the Great Recession, illustrated by the shaded area of the chart furthest to the right. While recovering slightly since the start of the recession, a substantial recovery has been slow to emerge, which is typical in the aftermath of a financial crisis. As a result, income per person is largely unchanged from the beginning of the decade.

Slow employment growth remains the most pressing challenge facing our recovery. Even while we experienced some income gains in the mid-2000s, those gains were not accompanied by a large increase in the employment-to-population ratio (which is the broadest measure of employment). In fact, the employment-to-population ratio never recovered from peaks reached before the 2001 recession. Due to the Great Recession, the employment-to-population ratio remains 6 percentage points lower than it was in 2000 and would be lower without the aggressive responses of the federal government and the Federal Reserve.

The December Job Gap

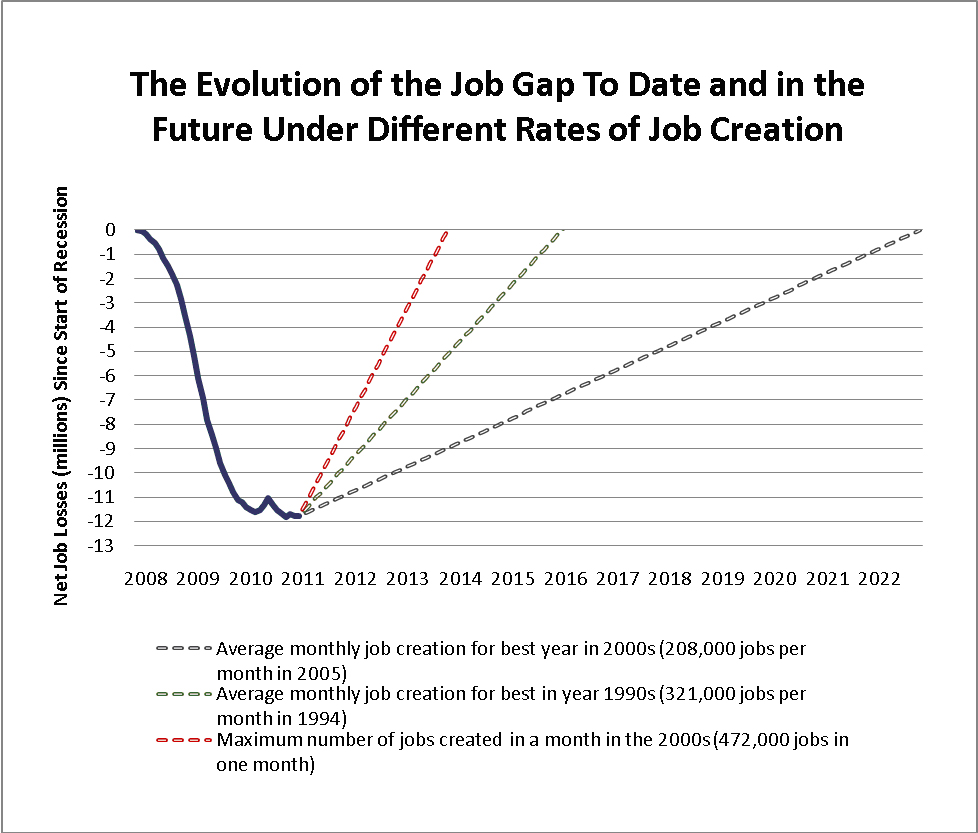

As in previous blog postings, The Hamilton Project explores the monthly “job gap” based on the employment numbers—or the number of jobs the economy needs in order to return to return to pre-recession employment levels while absorbing the 125,000 people who enter the labor force each month.

December’s job gap remains roughly unchanged since October 2010, at a gap of 11.8 million jobs.

Continuing our look back over the past decade, we can also see the evolution of the job gap since the start of the Great Recession in December 2007. The thick line in the chart below shows the net number of jobs lost since the Great Recession began.

The broken lines display the date by which the jobs gap would be closed under alternative assumptions about the rate of job creation going forward. If the economy adds about 208,000 jobs per month, the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 2000s, then it will take until November 2022 to close the job gap. At a more optimistic rate of 321,000 jobs per month, the average monthly rate for the best year of the 1990s, the economy will reach pre-recession employment levels by January 2016.

Unprecedented Challenges For the Decade Ahead

While there are some signs that the employment losses from the Great Recession have bottomed out, the economic challenges we face at the start of this decade are still daunting. Fewer Americans are at work than were 10 years ago and, from an income perspective, Americans are—on average—no better off.

Adding to our complex policy agenda, looming budget deficits at the local, state and federal levels threaten to limit future economic growth. Just as signs of recovery begin to surface, the fiscal situation could threaten our broader economic future. State and local budgets are of particular concern as stimulus funds dry up and states and municipalities are forced to cut key services and programs long before recovery has taken firm hold—as indicated above by the large jobs gap that still remains.

Next month, The Hamilton Project will release several policy proposals to aid state and local governments as they grapple with extreme budget constraints. The stakes are high: as policymakers set their 2011 agendas, it is with the knowledge that future economic growth, and the security of millions of Americans, depends on getting the policy outcomes right.

Commentary

New Decade, New Hopes for Job Growth

January 7, 2011