The October employment numbers, released today by the Labor Department, show tentative progress toward recovery. The U.S. economy is creating jobs for the first time in four months, with an increase of 151,000 jobs last month. The private sector added 159,000 jobs, continuing ten straight months of private sector job growth.

For the past few months, The Hamilton Project has examined the “job gap,” or the number of months it would take to get back to pre-recession employment levels (while absorbing the 125,000 people who enter the labor force each month). In this month’s posting, we also explore the impact of the Great Recession on the length of unemployment for many American workers and find that the number of long-term unemployed has risen sharply since the Recession began.

The Rise in the Number of the Long-Term Unemployed

The data confirm the story that we have seen in the papers and on every news channel about the long-term unemployed. Out-of-work Americans are experiencing longer spells of unemployment than in any recent recession; half of all unemployed workers in October have been unemployed for more than 21 weeks.

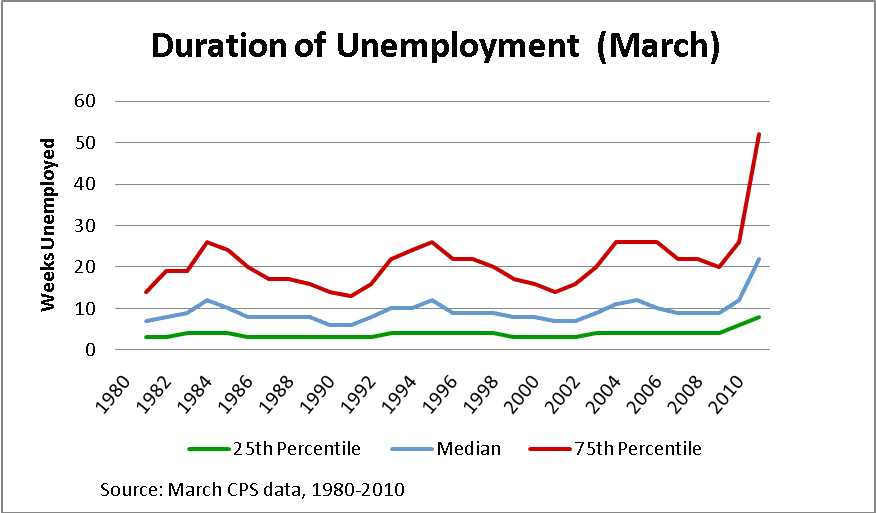

Furthermore, the most recent data indicate a quarter of the unemployed had been out of work for more than a year, while 10 percent have been unemployed for at least 2 years. A longer-term perspective is available from the March CPS in the graph below, which reports the number of weeks of unemployment for the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles of the unemployed population since 1980:

It is important to understand this rising trend in the long-term unemployed, as there are a series of consequences that have been shown to follow workers who experience these extended spells of unemployment long into the future. For example, job skills depreciate, job networks are depleted, and workers become discouraged. The longer a worker is unemployed the less likely he or she is to find a new job and the more likely he or she is to find only a lower-paying job.

There are also other, less obvious, consequences of long-term unemployment. According to research by Sullivan and von Wachter (pdf), in severe downturns, job displacement can lead to significant reductions in life expectancy of 1 to 1.5 years. Further, research by Oreopoulos, Page and Stevens (pdf) shows that the children of these workers are also hurt as they earn less when they become adults and enter the labor force.

This all suggests that the historically long durations of unemployment we are now experiencing will likely have a negative effect on the employment and earnings recovery of many Americans, even as the wider economy recovers.

The October Job Gap

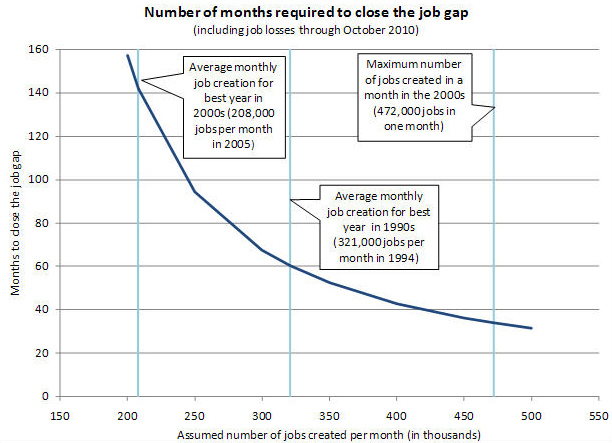

In past months, we have updated the job gap, which is the number of jobs the economy needs to add in order to return to pre-recession employment levels while absorbing the 125,000 people who enter the labor force each month.

This month, the job gap shrank to 11.8 million jobs, down from September’s gap of 11.9 million jobs.

To put this in context, we can explore how long it will take to fill the job gap at different rates of job creation. If the economy adds about 208,000 jobs per month, the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 2000s, then it will take 142 months, or about 12 years to close the job gap. At a more optimistic rate of 321,000 jobs per month, the average monthly rate for the best year of the 1990s, the economy will reach pre-recession employment levels in 60 months, or about 5 years. The chart below shows the number of months required to close the job gap at different rates of job creation.

Even under the most optimistic scenarios, it will take years to eliminate the job gap. Although many jobs were lost during the recession, some who have lost their jobs have been able to quickly find new jobs and return to work. Hopefully as the economy recovers, today’s unemployed will find jobs similar to the jobs they lost.

Conclusion

We are experiencing an unusual recovery on many fronts—including the historic rise in the long-term unemployed. This should be a serious issue of concern for policymakers for the many reasons noted above.

For workers experiencing long spells of unemployment, unemployment insurance is one tool to help ease the pain until the economy recovers. Congress acted to extend unemployment benefits back in 2008, and these extended unemployment insurance benefits are set to expire at the end of the month. If Congress does not act again, 2 million people, or about one-third of the long-term unemployed, will lose their benefits in December.

Commentary

The Great Recession’s Toll on Long-Term Unemployment

November 5, 2010