One of the perks of working at a university is the ability to look over students’ shoulders and see what they are reading. If one of those students is Sureshkumar Nair, a senior Indian government official here at the Sanford School’s Master of International Development program, you are sure to see something interesting. This week’s readings are inspired by one of his papers.

The article that first captured his – and my – attention is from The New York Times on February 8, 2017, Joyous Africans Take to the Rails, with China’s Help. The article is about how the Chinese designed, built, and financed a 466-mile line between Djibouti and Addis Ababa—the first transnational electric railway in Africa. Meanwhile, Power Africa, a USAID initiative launched by President Obama in 2013 to provide 60 million new electricity connections (600 million Africans do not have electricity), is falling short of its goals.

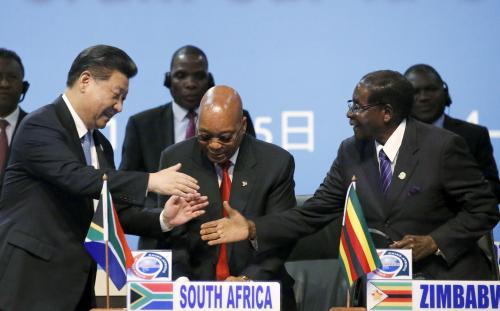

China’s global ambitions and expanding economic influence are surveyed by Clifford Krauss and Keith Bradsher. China’s government appears to be “seizing the opportunity” to extend its influence, not just in Africa but in countries like Ecuador, in America’s backyard. These investments have already made China the largest donor in many parts of the world, a rise that is captured stunningly in The World According to China. The graphs alone are worth your time.

There has been lots of discussion about China’s approach. If you are unfamiliar with the naysayers’ arguments, here is one that reckons that the game for China is “heads I win, tails you lose”.

But take a look also at AidData’s Tracking Chinese Development Finance website. It provides the latest numbers and early assessments of the quality of China’s assistance in Africa. One of them shows that African leaders direct Chinese aid to places of their own ethnicity; in contrast, World Bank assistance shows no such favoritism. Another assessment is more encouraging: political considerations don’t shape China’s aid allocations any more than those of western donors.

What makes all this especially relevant today is the contrast between attitudes about trade in Washington and Beijing. President Trump has made his dislike for trade deficits and foreign aid obvious.

But the U.S. was losing ground long before Mr. Trump came to Washington. In 2009, China overtook the U.S. as Africa’s biggest trading partner (In Trade with Africa, US Playing Catch-up). The U.S. could start turning things around by making distinctions between its trade deficits with different parts of the world. You want to run trade deficits with Africa, but not necessarily with Europe and Japan (and perhaps even China).

The new government in Washington should be paying more attention to trade and investment agreements like the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). AGOA was introduced in 1999 by a Republican congressman, signed into law by a Democratic president in 2000, and renewed and broadened subsequently by two more presidents—one a Republican and the other a Democrat.

Commentary

Future Development Reads: Getting smart about trade and aid to Africa

March 31, 2017