This post represents a moral compromise for me: I am generally doing my best these days to avoid being sucked into the vortex of the still 15-month-out presidential election, which seems to swallow up every Washington conversation these days. To my mind, it is important for as many citizens as possible to think about policy and politics as something other than extended horseraces. But many of you are already giddily riding the whirlpool, and so here we are.

The short answer: probably not. But, now that we have the final version of the Clean Power Plan, maybe! And that is news. What has changed? In short, the final rule sets much tougher targets for some swing states that would be crucial to determining a close election in 2016 if the contest were to be a squeaker in the mold of 2000 and 2004, (remembering that this is not actually the historical norm).

As I explained here last week, the final rule is significantly more demanding for high emitting states than the proposed rule was. It was possible to see the proposed rule as a kind of political accommodation to less green states (though the administration rejected that characterization), but the final rule is more intuitive: it is more demanding of intensive greenhouse gas emitters who have done little to control their emissions to this point. That is good news for those states who have already taken significant steps to curb their emissions, including west coast and northeast states, where the rule was already likely to be popular with voters even in its more demanding form.

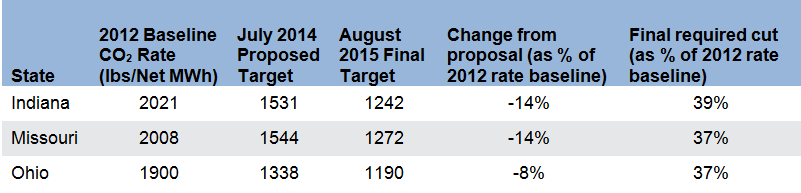

The changes to the final rule’s emission targets are bad news for a more electorally pivotal set of states including: Indiana, Missouri, and Ohio. All three of these states produce large amounts of coal power, and all are asked to make larger reductions in the final Clean Power Plan than they were under the proposed rule.

Most analysts would probably put Indiana and Missouri into fairly safe Republican territory these days, so perhaps Democrats don’t have much to lose by potentially making life more difficult for them. The 18 electoral votes from my native state of Ohio, on the other hand, remain central to nearly any strategy for victory in the presidential race. The fact that it confronts a noticeably more difficult path to compliance may make it more likely that the GOP nominee will eventually campaign hard against the Clean Power Plan. Especially if Ohio’s Governor, John Kasich, remains a viable presidential candidate and draws attention to what he calls “an unemployment plan” for the state.

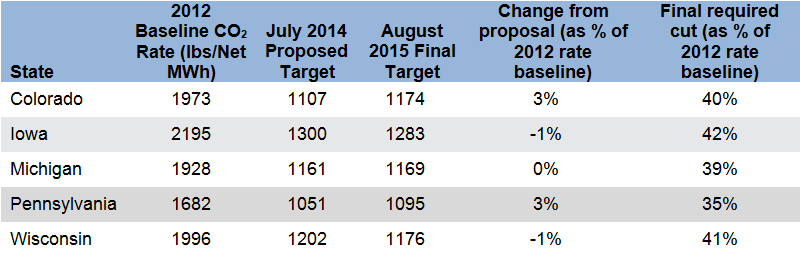

Among potential swing states, another group finds its situation basically unchanged under the final rule relative to the proposed rule but nevertheless faces a hard slog toward compliance.

All of these states were solidly in the Democrats’ column in the 2008 and 2012 elections, but at least some people tell stories in which they might provide support for Republicans in a close election. To the extent that Republicans want to put these states in play, highlighting the onerousness of the Clean Power Plan could be an effective strategy. (Many of these states are also likely to be contesting the Clean Power Plan on legal grounds, perhaps enhancing its newsiness during the campaign.)

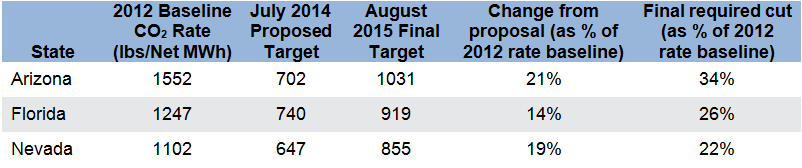

Of course, we should also note the flipside of these arguments. For some states, the final rule makes compliance considerably easier than the proposed rule did, including some potential swing states.

In each of these states, Republicans will now have a harder time selling the idea that the Clean Power Plan asks for unattainable emissions cuts.

If we step back for a moment from the specifics of the Clean Power Plan, we can find plenty of reasons why either party might decide to make climate change a prominent campaign issue. For Republicans, the Clean Power Plan is a prominent example of what they consider to be executive branch overreach in service of inefficient and economically counterproductive regulation. For Democrats, the issue looks like an opportunity to spotlight the GOP’s “backwardness” by making the discussion about prominent Republican denials that climate change represents any kind of appropriate object for government concern. Most political insiders seem to think that the downsides for each party in battling on climate change, coupled with most voters’ lack of urgency on the issue, will lead it to be a minor issue in the 2016 campaign.

But if that turns out to be wrong, and if Republicans gain traction criticizing the Clean Power Plan, and if the 2016 election has us waiting on precise vote tallies from the Buckeye State—well, you heard it here first. (Second).

Note: 2012 carbon efficiency baseline and final rule targets taken from EPA documents available here; proposed rule targets available here, presented in map form here.

Commentary

Will the Clean Power Plan swing the 2016 Presidential Election?

August 11, 2015