In January 2007, Uganda launched a national Universal Secondary Education policy, which increased enrollment at this level for both girls and boys. However, the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) and UNESCO studies on Uganda noted that many children drop out of secondary school and that girls leave more often than boys. In 2000, of the 518,931 students in secondary schools, girls accounted for 44 percent; and, by 2010, of the total 1,225,692, the figure had increased to 46.6 percent. However, country-level data show that only 27.58 percent of girls completed secondary school in 2013, compared to 31.13 percent of boys.

Various reasons are cited for the girls’ high dropout rates. The ICRW reports that economic factors, linked with cultural and traditional practices, are the main obstacles. (1) When girls are 11 to 13 years old and reach puberty, parents force them to marry so the families can benefit from the fee (called a bride price) that grooms pay to wed their daughters. Soon after, girls become pregnant and drop out of school. (2) Young girls face challenges dealing with menstruation: They do not have sanitary napkins since families cannot afford them. Thus, girls stay home during this time because the materials they use (in place of napkins) do not protect them for the full school day. (3) Girls are assigned time-consuming household chores. (4) In most cases, they are a key source of economic support for the family, working as laborers in other families’ fields or as house maids. Thus, they miss a good deal of school, perform poorly, and ultimately drop out.

“A senior woman teacher is someone who has been entrusted by the school management to stand in for students in case they have problems, more so the girl child who faces problems at school, home and outside the world, she encourages them to help themselves, be courageous and determined in everything they do.” 15-year-old girl, Uganda

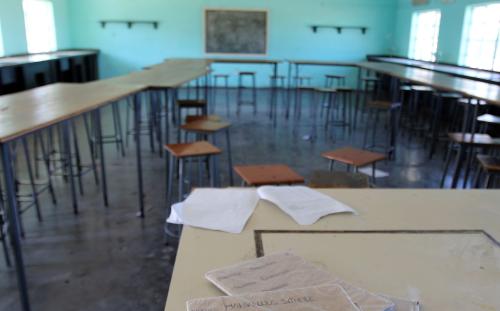

Despite the SWTs’ positive work as mentors, those I interviewed said they faced various challenges: (1) Their responsibilities are not clearly designated, either by the schools or Ministry of Education; (2) They have heavy workloads, because they must also teach a full schedule of classes, which leaves little time for interacting with the girls; (3) They lack facilities, such as an office or room, in which to meet privately with girls; (4) They lack funds to cover materials like sanitary napkins; and (5) They lack support from parents and other teachers.

These challenges seem to have surfaced because the policies and guidelines do not clearly define the SWT position. Indeed, the National Strategy for Girls’ Education in Uganda (2014-2019), acknowledged the position and its responsibilities were not well defined.

While at Brookings as an Echidna Global Scholar, I will continue to explore whether the SWT helps girls complete secondary school; and, if it does, I will recommend policies to strengthen the position at the national level and ways to raise awareness about its importance at the local level.

Commentary

Senior women teachers in Uganda secondary schools: Tapping into their potential to improve quality education for girls

September 20, 2016