In rural Nepal, girls face countless barriers that prevent them from enrolling and remaining in high school. Some relate to cultural and family traditions; others to school practices and facilities.

Regarding the former, some rural families still follow the centuries-old custom of Chhaupadi (when women are kept in isolation during menstruation), which prevents girls from attending school or participating in family and community activities. Further, family members typically do not give girls the information they need to manage their bodily changes during puberty and adolescence; thus, they worry, which affects their concentration and capacity to study. In addition, parents often expect their daughters to be responsible for a heavy load of household chores, at the same time that teachers’ expect the girls to study a great deal, to pass national exams and complete high school with good scores.

One question I am often asked is, “Why and how did you—as a male—become interested in girls’ or women’s issues?” My response is that equity prevails only when men and women understand each other’s problems. I was fortunate that my mother asked me to do household chores and in assuming them, and through her model, I became aware of women’s many responsibilities.

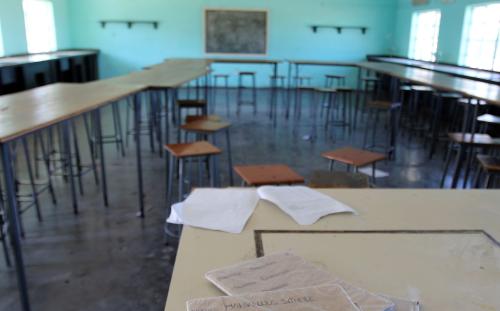

What’s more, the conditions of the schools present challenges as well. Many do not have toilets that are private and functional, and some are without toilets altogether—an issue that affects girls more than boys. The schools also lack counseling about managing menstruation and hygiene. Thus, such obstacles make it more likely that girls will drop out of school (usually in high school or grade 8), or fall behind in their studies.

What’s being done to help?

To empower girls of this age, my team (which included a female medical doctor, a gender expert, a nurse, and an education specialist), supported by the U.S. Embassy in Kathmandu, launched the Girls’ Empowerment Program: Managing Adolescent Challenges in Rural Nepal in three districts. The five-day program included teaching a range of study skills and strategies to overcome the barriers listed below.

The girls were taught how to manage the following:

- The challenges that come with adolescence

- Menstruation hygiene

- Study skills

- Time management for school and household tasks

It also taught leadership and problem-solving skills through what we call the students quality circle.

In addition, we brought parents and teachers together for one session to discuss ways they can support their daughters: These include treating them normally when they have their menstrual periods (as opposed to isolating them), helping daughters make sanitary pads with the material from old clothing, and reducing the girls’ household tasks when they are studying for exams. Further, local female leaders, officials in local agencies, and those from the U.S. Embassy in Kathmandu spoke to the girls, shared their experiences, and inspired the girls to set goals to finish high school and even continue with college. At the end of the five days, the girls developed one-year plans to pass on the skills and information to other girls in the school and community.

Is it working?

Post-training feedback and a follow-up study indicated that the program did empower the girls and helped them address the challenges they face while in high school. Moreover, they are sharing the information they acquired with others girls.

Also, some are leading school clubs and volunteering in the community. Equally important, the team convinced many parents to allow their daughters to stay in school (in general), and while they have their menstrual periods (in particular).

“First, I improved my public speaking. I also learned about the physiological changes during puberty and adolescence and how to deal with menstruation. I now value and manage time for my study. I learned that women can lead the nation. We should all contribute to developing the country. After the training, we shared what we learned with all the girls from grades 5 to 8 and now plan to share it with others.” -Hemanti Thapa

What are the next steps?

I based the program on observations I gathered while visiting communities for my research, along with my experiences teaching grades K-12 in rural and urban schools. Since the program has demonstrated positive outcomes for many girls, l’ve been presented the opportunity through the Echidna Global Scholar to develop strategies to scale up the effort and produce a model that can be adopted more widely in Nepal. This scaled-up model will draw and improve upon the strengths of the initial program. For example, we can begin to address some second-generation priorities, such as providing access to school (where this is a problem), dealing with harassment, and transitioning to the next educational level. Ultimately, the hope is to expand this model to other countries since these problems are certainly not limited to Nepal.

Commentary

Inspiring Nepali girls to take control of their lives

September 16, 2016