In a little over a year from now, Democrats will have a presidential nominee and the race will be on with President Donald Trump. At that point, Trump will no doubt take a play out of the standard Republican playbook and try to brand Democrats as liberals, or even socialists.

Rick Hess of the American Enterprise Institute recently argued, in similar fashion, that “Joe Biden, the most centrist candidate in the Democratic field, has sketched what would be the most energetically liberal presidential agenda [on education] in American history” and, yet, that Biden’s proposals are “measured and centrist” compared with the rest of the Democratic field. Putting these two pieces together, he concludes, “It’s pretty clear that any Democratic nominee is going to set a high-water mark for liberal activism when it comes to education.” Moreover, he adds, “In education, as in so many other things, Washington may be set to get even more partisan” on these issues. Is he right?

Not exactly. The Democratic candidates’ positions do involve considerable new spending, and at the federal level—both hallmarks of American liberalism. But the positions are less liberal and less partisan than they appear and align fairly well with what the electorate as a whole seems to want.

The Democrats’ new approaches

In my other recent posts on education policy in the 2020 Democratic primary, I argued that education would be an especially important issue in the primary and that charter schools and free college would be litmus test policies.

Another key issue in the race is school spending. Teacher unions and school boards have long fought for more resources, but primarily at the state and local levels. They filed—and often won—funding “adequacy” lawsuits to get states to lift spending, especially in low-income school districts. This worked well for several decades. The lawsuits led to more spending, which helped raise student outcomes, particularly for students in low-income districts where these funds were mostly targeted.

In the race for the party’s nomination, the aim is still similar—more funding—but we see three shifts involved: Those seeking more spending are using a different strategy (legislation instead of lawsuits), at a different level of government (federal instead of state), and for different levels of the education system (higher education and pre-K, in addition to K-12).

K-12 spending proposals

Most of the presidential candidates have embraced some combination of the following two main ideas:

1. Increase Title I funding

Increasing Title I has the advantage of being easy to implement and gives districts considerable autonomy in how the money is used (so long as students from low-income families are the primary beneficiaries).

2. Increase teacher salaries

Another idea is to target resources specifically to teacher salaries. Now, you might think that, since K-12 spending is comprised mostly of teacher compensation, increasing school spending would also increase teacher salaries. While those facts are right, the logic is not. What is true on average is not necessarily true on the margin. As Fordham Institute President Michael Petrilli recently highlighted, increased spending has not led to increases in teacher salaries. Instead, the funds have been used to hire more teachers and administrators (at the same salaries) and to increase teacher compensation in the form of health benefits and pensions. So, even a massive increase in Title I spending might not do much for teacher salaries.

The idea of giving teachers a raise is gaining traction thanks in part to a proposal floated by the Center for American Progress (CAP). It is not hard to see why Democrats would support this. Teachers are a key constituency and teacher salaries today are below what they were in 1994 (adjusted for inflation). As the CAP report shows, a fixed dollar tax credit would be fairly easy to implement at the federal level. While not technically a raise, it could be designed in a way that is effectively the same thing. (Also, see these other analyses on the candidates’ specific teacher salary proposals.)

As I wrote previously, Democrats are also pushing for spending changes in pre-K and especially higher education. If Democrats get their way—and, as I argue below, they probably will eventually—this will represent a fundamental reshaping of the federal role in education.

Why these really aren’t as liberal as they might seem

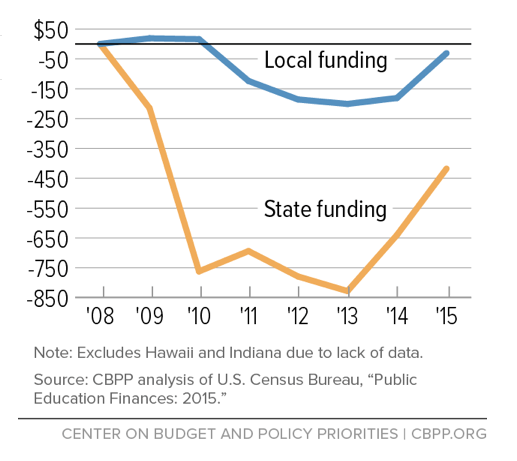

Again, this all sounds liberal. What else would you call a massive increase in federal spending? I would call it “filling in for the states.” Figure 1, from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), shows the sharp drop in state and local funding for K-12 schools in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis—and that, a decade later, we are still not back to pre-crisis levels. This drop very likely reduced student outcomes.

Figure 1: The Decline in State and Local Spending on K-12 Schools (Inflation-Adjusted)

Biden’s proposal to “triple” Title I is therefore a drop in the education bucket. Spending on the program is currently only $15.8 billion annually. Tripling it would increase total K-12 spending on public schools by less than 5%, not enough to make up for recent losses.

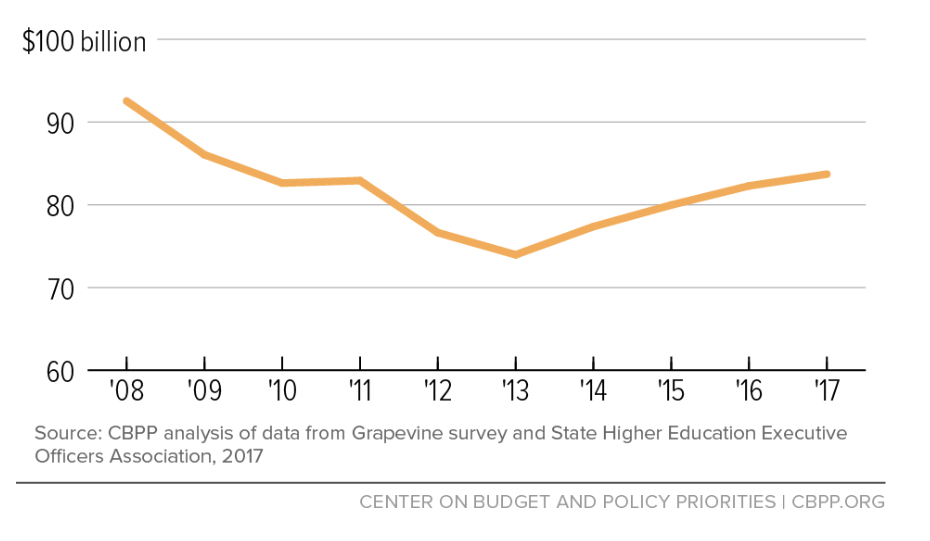

We see the same thing in higher education. Figure 2, also from CBPP, shows the sharp drop in state and local funding for higher education. Another analysis shows a similar result: per-pupil spending is down 11% from 2008-2018.

Figure 2: The Decline in State Spending on Higher Education (Inflation-Adjusted)

The fiscal conservatives at this point are probably thinking, “So what, government spending has been increasing for decades—it’s time they took a haircut?” But this is faulty reasoning in part because education suffers from the “cost disease.” This means it is difficult to make productivity improvements in many service sector industries like education. Further, schools and colleges have to compete for labor with those sectors where productivity does improve—industries that pay higher salaries as productivity improves. This means the education sector has to spend more every year just to stand still.

A truly “moderate” goal would be to keep education spending at a constant share of economic activity (GDP). Yet, spending is also fairly modest, and declining, on this measure, too. We are spending less on education now as a percentage of GDP than in 1970 and only slightly above the world average of 4.8%.

The 2008 fiscal crisis is not just a temporary blip either. As I argued in my first post in this series, state and local budgets are going to be increasingly taken up with health care spending and plugging holes in public sector pension plans. States could raise revenue, but this is unlikely politically. Also, they can’t borrow the way the federal government can. This means that the only way to maintain (let alone increase) real resources is by increasing the federal role—exactly what the Democrats are proposing.

The upshot is that something like the proposals of the Democratic candidates will be necessary even to maintain our middling educational resources. While it might be liberal for these resources to come from the federal—rather than state and local—government, the total level of resources seems at least as important for judging how liberal the policies are.

Put that way, the Democratic proposals don’t sound liberal at all.

Why the Democratic proposals aren’t as partisan as they might seem either

The other key point is that all of the above proposals have bipartisan support. Table 1 shows the percent support and net favorability (support minus opposition) for the general ideas being discussed by Democrats, drawing from multiple polls. (Polls of specific candidate proposals do not exist to my knowledge.)

Table 1: Voters’ Support for Education Policy Reforms

|

Democrat % Support |

Democrat Net Favorable |

Republican % Support |

Republican Net Favorable | Overall Net Favorability | |

| Spending Proposals | |||||

| Increase School Spending | 58% | +52% | 33% | +18% | +37% |

| Increase Teacher Salaries | 59% | +55% | 38% | +28% | +42% |

| Free College (2017) | 80% | +67% | 47% | +2% | +34% |

| Free College (2019) | 68% | +42% | 14% | -70% | -7% |

| School Choice Proposals | |||||

| Charter Schools | 32% | -16% | 47% | +12% | -3% |

| Vouchers – Universal | 47% | +12% | 64% | +37% | +23% |

| Vouchers – Low-Income | 47% | +6% | 39% | -10% | -1% |

Sources: The data for school spending, teacher salaries, charter schools, and vouchers come from the 2018 Education Next poll. In both cases, they reported results for different ways of wording the questions and I took the version with the least support. The data for the 2017 and 2019 free college polls are from Morning Consult/Politico and Quinnipiac.

We see clear support for increased school spending. For example, both increased school spending and increased teacher salaries have net favorability of +37% or above, meaning that the average voter is much more likely to support than oppose these ideas. That support is also fairly bipartisan, with Republican net favorability at or above +18% on both proposals. Only 33-38% percent of Republicans support these ideas, so the positive net favorability suggests that most Republicans want to keep spending and teacher salaries basically where they are now (or have no opinion). But I suspect that those polled were unaware of the recent declines; and note that I have chosen the polling results that are least supportive of my own arguments. Other ways of wording the questions on K-12 spending show more support from Republicans.

Polling on free college is more complex. The idea seemed to have broad support in 2017 with 63% supporting and 29% opposed, and even a majority of Republicans in support. But since the Democratic candidates started talking about it more, support for the idea has fallen, with 45% opposed and 52% supportive. The survey methodology and poll question wording are different in the two surveys, but not in ways that would obviously explain this.

One likely explanation for the apparent decline in support for free college is that the Democratic campaigns themselves have led to splintering on this issue—Republicans support ideas less when Democrats embrace them. As further evidence of Republication support, note that one of the first and most well-known free college proposals came from a Republican in the very red state of Tennessee, Gov. Bill Haslam. This signals that Republican opposition is soft and that, once the political campaigns die down and the public can start to think about policy rather than candidates and parties again (at least a little), the underlying support might show through again.

Government funding for early childhood education has also had longstanding and broad support. While the most widely cited poll is from an advocacy group, the general pattern seems to hold even in red states like Georgia, where there is also widespread support—even when the question is worded to signal that this would come with higher taxes.

Viewed in this light, the Democratic proposals are not very partisan. Democrats obviously support the proposals of their candidates more than Republicans do, but what is noteworthy is the often-positive favorability among Republicans.

However, there are some areas where I partially agree with Rick’s interpretation. He points out not only what is included in the Democratic proposals, but what is omitted. In particular, he brings up school accountability, which does indeed have broad support—roughly 70% in both parties support annual student testing, for example. But the silence reflects tacit support for the current state of affairs—i.e., the very policies that moderates put in place throughout the 1990s and 2000s. It’s hard to build a campaign around “keep existing policies the way they are.” If any Democrat had proposed more federal accountability and standards, they wouldn’t have been seen as moderates but as out-of-touch, big government liberals.

Democrats are also not promoting boycotts on standardized testing or expanded multi-cultural education or sex education. Those would be truly liberal policies. There is some talk of school integration, but there are no specific proposals and the potential for federal intervention is quite limited.

Support for school choice is interesting for a different reason. The Education Next poll shows that charter schools and vouchers (see Table 1 again) have large numbers of supporters and opponents, and few undecideds. This is true for both Democrats and Republicans, which is why it presents a tricky issue in both parties. The Democratic candidates are dealing with this by hovering in the middle; the most extreme positions are a moratorium (no growth) and a ban on for-profits (which constitute only 12-18% of charters). In any event, it seems more accurate to say school choice is divisive (people have strong opposing views on it) than it is partisan (party affiliation doesn’t explain the differences in those views). Education has always made for strong bedfellows and school choice is a good example.

Conclusion: The role of the federal government in education is about to change

In summary, Democrats’ education proposals are not nearly as liberal or partisan as they might seem. When we look at government spending in total, the party is mostly trying to stay the course on total K-12 and higher education spending levels, and only shifting funding to the federal level. These seem to be stands that the electorate broadly supports, which is partly why almost all the Democrats candidates are singing from the same education songbook. Some Republican members of Congress, even in our hyper-partisan era, would probably vote for these policies without putting up much of a fight. The more moderate Democrats are more in the ideological and political middle than the Republicans are right now and seemingly building a bigger tent.

There is a larger implication of all of this: The broad Democratic support for education spending—from birth through college—combined with a fair degree of Republican support means that the federal role in education is likely to change in the next five to 10 years. Stalling state and local funding will create demands on the federal government to pick up the slack. This, in turn, will create renewed pressures for accountability, not only for traditional public schools, but charter schools as well. More spending at the higher education level would also mean revisiting accountability, making federal higher education policy look more like K-12 policy.

We may be in the beginning stages of a fundamental restructuring of the role of the federal government in education that would bring more education spending and accountability from Washington, D.C. If a Democrat wins the presidency in 2020, then that restructuring may come sooner rather than later.

Commentary

Are the education proposals of the Democratic presidential candidates really that liberal?

June 26, 2019