When state and local governments need to borrow money, they often do so by selling municipal bonds—promises to pay investors a fixed amount of money at a future date. Before the pandemic began, state and local governments were mostly in very good shape, most of their bonds were considered very safe, and interest rates were low, so they could borrow at low rates without any trouble.

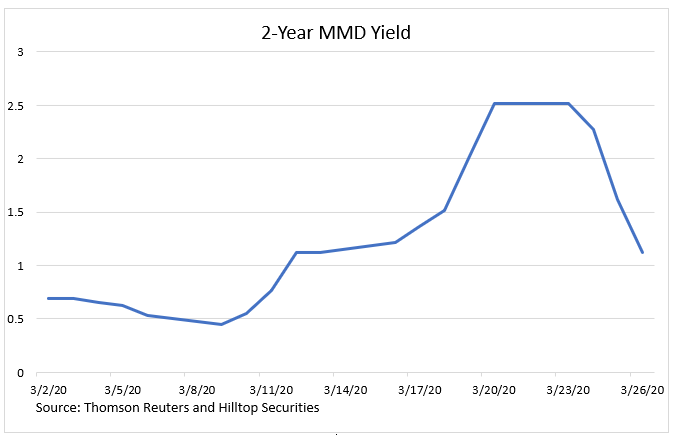

As the coronavirus outbreak worsened, that changed. Investors began withdrawing from municipal mutual funds: For the week ending March 18th, investors withdrew a record-setting $12 billion—almost 2.5 percent of assets—and another $13.7 billion the following week. Between March 9th and March 20th, state and local governments managed to sell only about $6 billion of the $16 billion in bonds they were seeking to issue. These withdrawals were accompanied by sharp increases in the interest rates borrowers were required to pay. From March 9th to March 24th, the Municipal Market Data yield—a measure of municipal bond yields produced by Thomson Reuters and commonly used as a pricing gauge by state and local bond issuers—went up by roughly 2 percentage points, a huge increase for this market.

At a time when they are already under enormous stress from the coronavirus outbreak, state and local governments suddenly found it hard to borrow.

Why does it matter?

Most states have balanced budget requirements, so they generally don’t run budget deficits like the federal government frequently does. But government revenues tend to come in large chunks—for instance, at tax filing deadlines—whereas major expenditures might come at different times of the year. Issuing debt can help state and local governments smooth out cash flow issues that result when spending obligations don’t coincide with incoming tax revenue.

In addition, because of the Treasury’s decision to delay the federal tax deadline from April 15 to July 15, many state and local governments will have to wait three months longer than expected to get their tax revenues. This could create a cash crunch which makes borrowing money particularly important. And municipalities that cannot borrow may be forced to cut back on services. The city of Cincinnati, for example, recently decided to furlough 20 percent of its workers in part because of the expected decline in tax revenues due to the coronavirus.

Why did the muni bond market dry up?

When uncertainty is high, investors usually sell risky assets and buy safe assets—a phenomenon economists call flight-to-safety. Normally state and local bonds are considered extremely safe assets. As recently as late January, most, although not all, state and local governments looked in decent shape to weather the next downturn. Their rainy day funds—which they draw down when other revenues dry up—were at a record high. The average Fitch rating for state governments was AA+, and the average rating for local governments was AA. So, with the coronavirus creating large and uncertain economic costs and the stock market in free fall, why weren’t investors snapping up municipal bonds as soon as they were issued?

One possibility is that investors started to view municipal bonds as riskier than previously thought, and therefore began demanding higher returns to hold them. State and local budgets are, after all, going to be hit hard by the coronavirus. Tax revenues will fall, and spending on social insurance programs like unemployment insurance and Medicaid will increase. But that doesn’t appear to have been the main problem in March.

A more likely explanation is that, given frictions in financial markets, investors simply wanted to hold onto cash instead of buying municipal bonds. Therefore, they started selling the bonds or mutual funds they had and stopped buying any new issues. Indeed, once it became clear that the Federal Reserve was going to support municipal bond markets, yields fell back somewhat.

How did the Fed respond?

On Friday, March 20th, the Fed began to accept short-term municipal bonds purchased from mutual funds as collateral for lending to banks through the recently re-launched Money Market Mutual Fund (MMLF). Three days later, on Monday, March 23rd, the Fed began to accept a wider range of municipal bonds as collateral for lending through the MMLF and the Commercial Paper Funding Facility.

By accepting short-term municipal bonds as collateral for lending to banks, the Fed made it easier for banks to turn municipal bonds into cash, making them more attractive to hold. The Fed actions rapidly had the desired effect. By March 24th, Tom Kozlik, the head of municipal strategy for Hilltop Securities, saw a “significant level of improvement in market behavior.” Between March 23rd and March 30th, the MMD yield fell by roughly 1 percentage point.

The recently enacted “Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security” (CARES) Act includes $454 billion to backstop Fed losses on lending directly to businesses, states, and municipalities, as well as $150 billion in direct federal aid to states and municipalities. The Fed has announced a couple of new programs to lend directly to major corporate employers, and says it expects to announce a Main Street Lending Program—a program for lending directly to small businesses—soon. However, so far there are no plans in place to lend directly to state and local governments. Nevertheless, by giving the Fed the ability to start such a program, the CARES Act may have contributed to calming down the municipal bond market.

Commentary

What’s going on in the municipal bond market? And what is the Fed doing about it?

March 31, 2020