The Vitals

Charter

schools are tuition-free, publicly funded schools. Charter school leaders

accept greater accountability in exchange for greater autonomy. About 3 million

students attend charter schools across 43 states and the District of Columbia.

Assessing whether charter schools work is a complicated question. While the

last four U.S. presidents—Clinton, Bush, Obama, and Trump—all expressed support

for charter schools, support is splintering along party lines.

-

About 3 million students attend charter schools across 43 states and the District of Columbia.

-

Compared to traditional public schools, a disproportionate share of charter school students are Hispanic (33%) or Black (26%).

-

Assessing whether charter schools work is difficult because doing so requires clarity about their goals and good measures of how well they achieve those goals.

Watch

A Closer Look

What is a charter school?

Traditionally,

local school districts operate public schools. They make decisions about how

schools run, in some cases through collective bargaining agreements with

teachers unions. Most students are assigned to traditional public schools based

on the neighborhood in which they live.

Charter

schools operate differently. A charter school begins with an application that

describes the proposed school’s mission, curriculum, management structure,

finances, and other characteristics. That proposal goes to a

government-approved authorizing agency such as a school district or a university.

Who can serve as an authorizer—like many aspects of charter school law—varies

from state to state. If the authorizer approves the proposal, it creates a

contract (“charter”) with the school’s governing board that describes the

school’s rights, responsibilities, and performance expectations. This is the core

of what has been called the “charter school bargain.” School leaders accept greater

accountability (e.g., the possibility of closure for poor performance) in

exchange for greater autonomy (e.g., the ability to pursue a specialized theme).

Along with

accountability and autonomy, the other principle at the foundation of the

charter school model is choice. Students are not assigned to charter schools

based on where they live. Instead, their families request a seat in the school.

Some cities use unified

enrollment systems that allow families to request many schools at

once, ranked in order of preference, and then assign students to schools using

a placement algorithm.

The

principles of accountability, autonomy, and choice are interconnected. For

example, choice serves as a form of market accountability (since schools must

attract families to stay open), while school leaders can use their autonomy to differentiate

themselves and create a rich assortment of choices for families.

Why are charter schools controversial?

Since their

formative days in the early 1990s, charter schools have drawn support from

unusual political coalitions, with different groups seeing different opportunities.

Many conservatives like the market competition and limited government control. Many

progressives like that all families, not just the wealthy, get to choose their

children’s schools. Even some union leaders saw early promise in charter

schools as a way to give teachers more voice in how schools run. In fact, the last

four U.S. presidents—Clinton, Bush, Obama, and Trump—all expressed support.

However, the

politics of charters are changing. Teachers unions have long been charter

schools’ most powerful opponents—they are skeptical that charter school

teachers actually have more control and frustrated that only

11% of charter schools employ unionized teachers. More generally,

support is splintering along party lines as Democrats—especially

white progressives—have become increasingly opposed. Some of this

polarization predates the Trump administration. For example, many prominent

Democrats, including Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, opposed a 2016

Massachusetts referendum to allow more charter schools (a referendum that was

soundly defeated). However, the emergence of President Trump and Secretary of

Education Betsy DeVos as the most prominent charter school supporters has accelerated

the polarization in public opinion.

The specific

critiques of charter schools vary. For example, some dislike that charter

schools attract public funding (and students) that otherwise would have gone to

traditional public schools. Others dislike that for-profit education management

organizations can operate charter schools in some states (about

12% of charter schools had this status in 2016-17, according to the

National Alliance for Public Charter Schools). Others worry about a lack of transparency

or public control—or that charters haven’t

lived up to their promise.

Who attends charter schools?

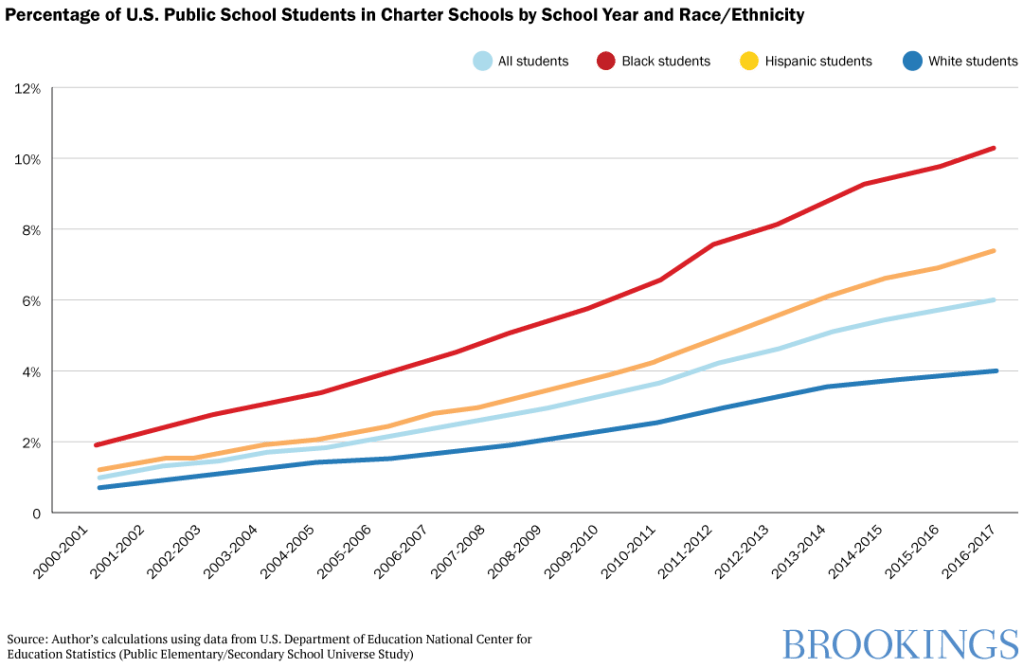

Despite the attention these schools get, only about 6% of U.S. public school students attended a charter school in 2016-17. As illustrated by the light blue line in the figure below, this percentage has increased since the turn of the century, although the rate of growth appears to be tapering off.

Notably, a

disproportionate share of charter school students are either Hispanic (33%

of all charter students) or Black (26%). More than 10% of Black

public school students and 7% of Hispanic public school students attended a

charter school in 2016-17, compared to about 4% of white students.

This

partly reflects the fact that a much larger share of charter schools (57%) than

traditional public schools (25%) are operating in cities.

In many

cities, including Detroit and Washington, D.C., a majority or near-majority

of public school students attend a charter school. At the extreme end of the

spectrum, New Orleans has an all-charter public school system.

Do charter schools work?

Assessing

whether charter schools work requires clarity about their goals and good

measures of how well they achieve those goals. It is not clear that we have

either.

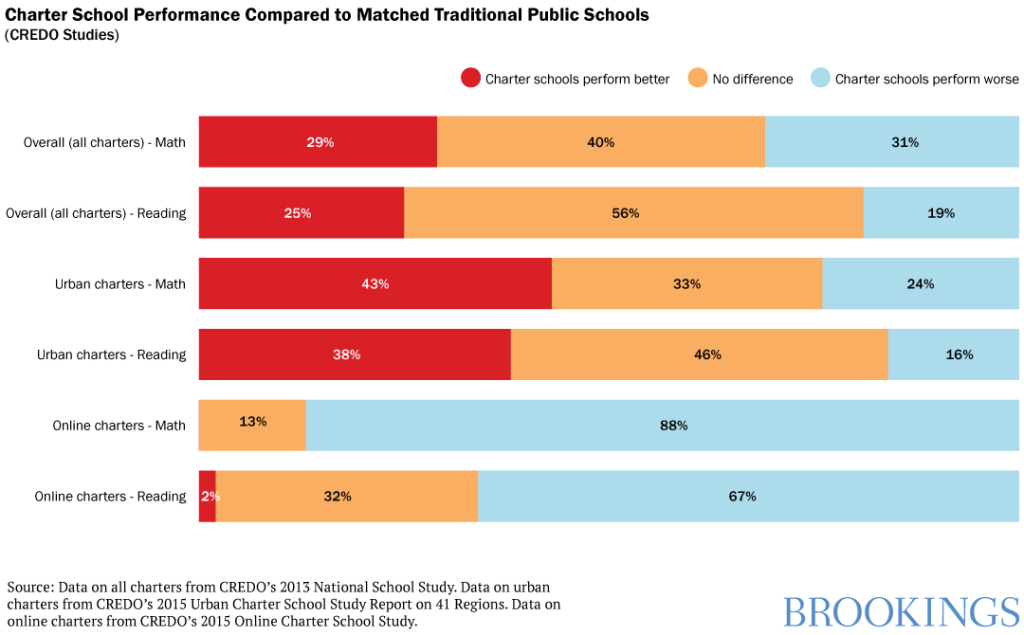

The most

commonly reported studies compare students’ academic performance in charter versus

non-charter schools. These comparisons are methodologically challenging, since charter

school students differ from other public school students in ways that could

affect their performance. Researchers need to find reasonable comparison groups.

One

approach is to examine the random lotteries often used when a school receives

more applicants than it can accommodate. Researchers tend to find that lottery winners

perform much better than lottery losers, but these comparisons come with major

caveats. Only schools with excess demand conduct lotteries, and it’s no

surprise that students who get into the most sought-after schools perform well.

The Center

for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University has taken a

different approach. CREDO obtains student-level data from many states and

districts and then matches charter school students with traditional public

school students who appear similar in many ways (e.g., students of the same

race, gender, and poverty status, with similar prior test scores, who

previously attended the same schools). Then they compare charter students’ test

scores with the scores of their matched non-charter pairs. This method isn’t

foolproof—for example, the variables used for matching could miss something

important—but it is probably the best approach to date for charter/non-charter

comparisons that represent the broad population of charter schools.

The figure below shows some notable results from the CREDO studies. The key takeaway is that charter school students, in general, perform about the same as their matched peers in the traditional public schools, but there is variation across different types of schools and groups of students. For example, students in urban charter schools generally perform better than their matched pairs—likely for an assortment of reasons—while students in online charter schools perform much worse.

However, we

should consider whether a charters versus traditional public schools comparison

is the right measure in the first place. Part of the rationale for charter

schools is that they should generate innovation and competitive pressure that improve

charter and non-charter schools alike. If those improvements occur—and there is

some

evidence for this—these comparisons might understate the benefits of

charter schools. If charter schools harm traditional public schools by, for

example, reducing funding or creating funding uncertainty—and there is some

evidence for this, too—these comparisons might understate the costs

of charter schools.

Regardless,

test score comparisons paint an incomplete picture of charter school

performance. We care about a much broader set of outcomes, including how

charter schools affect racial segregation, to what extent they create options

for disadvantaged families, and whether they are truly producing innovative

school models. The related research is too expansive for this overview but summarized

nicely in a 2015 NBER report.

What can policymakers do at the federal level?

When

presidential candidates talk about charter schools, it is more about politics

and principle than policy, since education is largely left to the states.

However, the federal government plays a role. For example, the U.S. Department

of Education administers the Charter Schools Program (CSP), which provides funds

to assist with matters such as charter school start-up, facilities acquisition,

and replication. Congress allotted $440 million for the CSP in FY 2019—a figure

that has increased substantially during the Trump administration. Federal

policymakers could increase or decrease overall funding and add or remove stipulations

for that funding (e.g., keeping federal funds from reaching for-profit charter

schools).

State and

local policymakers regularly make consequential decisions about charter schools.

These decisions cover a wide range of issues, including funding formulas, caps

on the number of schools or seats allowed, determinations of which schools (or

types of schools) to open, rules about which students get priority access to

high-demand schools, and requirements for open meetings and records.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What are charter schools and do they deliver?

October 15, 2019