Charter schools have been featured prominently in the news lately, with new poll data showing a growing racial divide in Democrats’ support for charters and Sen. Bernie Sanders’ call for a moratorium on public funding for charter school expansion. The news has offered a glimpse of the potential consequences for American students when changes in public opinion toward charters collide with presidential politics.

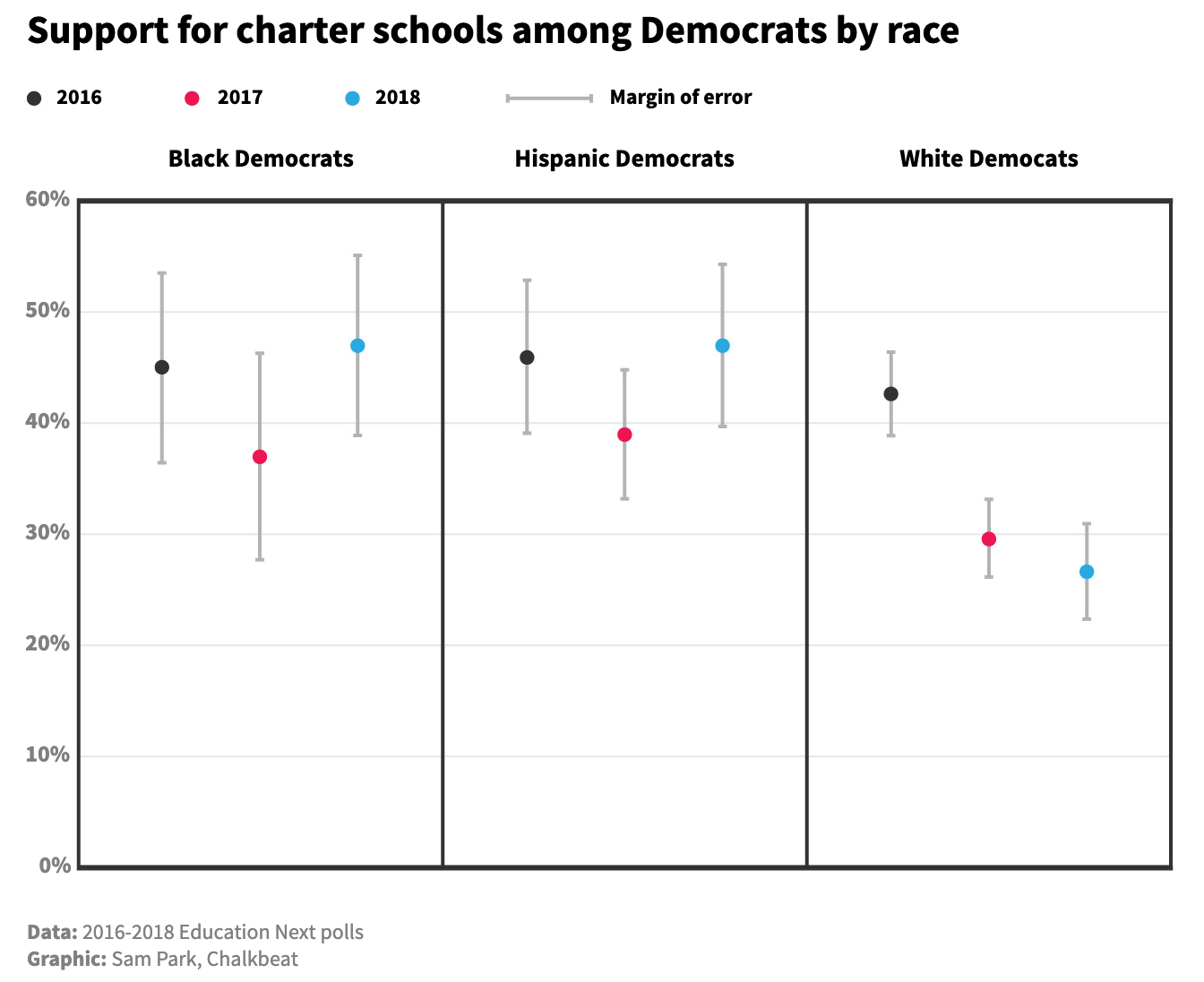

As one who studies charter schools, I see reason for concern—and maybe a little reason for optimism—in the developments. Charter schools educate disproportionately large shares of black and Hispanic children. Support for charters looks reasonably strong and stable among black and Hispanic Democrats, but it looks weak and is plummeting among white Democrats. The result, I argue, is a risk that growing ideological opposition to charters among white Democrats will have tangible, unwelcome consequences for families of color.

Education reform has an ugly tendency of being done “to and not with” communities of color. While it’s possible that growing skepticism from white Democrats—and pledges to act from candidates like Sanders—will help with cleaning up some of the problems with today’s charter schools and policies, the potential for harm is real.

Evidence of diverging views between white and nonwhite Democrats

New poll results from Democrats for Education Reform, an advocacy organization that supports charter schools, show a stark contrast between the attitudes of white Democrats on one side, and black and Hispanic Democrats, on the other. Among white Democratic voters, 26% expressed favorable opinions toward charters, while 62% had unfavorable opinions. The results were essentially flipped for black (58% favorable, 31% unfavorable) and Hispanic (52% favorable, 30% unfavorable) Democratic voters.

In response, EdNext examined its own data for an intraparty split. They, too, found such a split—along with evidence that it opened recently and quickly. Using EdNext data, Chalkbeat depicted an extraordinary drop in support from white Democrats from 2016 to 2018 without an accompanying drop from black or Hispanic Democrats:

As the Chalkbeat article explains, the precise cause of these patterns is unclear. One possibility is that charter schools have had a more personal and consistent presence in the lives of black and Hispanic Americans. A 2018 study from Public Agenda reports that 57% of charter schools, compared to only 25% of traditional public schools, operate in cities, and the charter school student population is disproportionately nonwhite (e.g., 33% white, 32% Hispanic, 27% black). If white Democrats, as a whole, are less likely to have opinions of charters rooted in personal experiences, then the emergence of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos as the poster child of school choice reforms—and Democrats’ reactions to her seeming antipathy toward traditional public schools—could explain the sudden shift in opinion.

Of course, poll results offer a limited view of what people believe, both because of challenges in accurately and precisely measuring group opinions, and because group opinions mask the variation, nuance, and complexity of views within groups. Views on charter schools certainly fit this description, as evidenced by the NAACP’s own call for a moratorium on charter schools—and internal resistance to that decision.

A proposed moratorium from Bernie Sanders

Sanders released his vision for charter schools as part of a broader plan for public schools. In a section titled “End the Unaccountable Profit-Motive of Charter Schools,” he describes charter schools as unaccountable and failing to fulfill their promise while draining resources from traditional public schools. He pledges to fight for bans of for-profit charter schools and a moratorium on public funding for charter school expansion until audits determine their state-specific impacts. He also suggests specific rules for charters related to transparency, governance, and unionization.

Some of the reporting on the Sanders plan—and the response from charter school advocates—overstates the impact that Sanders can have on charter school policy from the federal level or understates what there is to like about the plan. The plan contains some good ideas. Recent efforts to improve charter school transparency in California and Washington, D.C., for example, have drawn attention to the weak transparency laws in many states (e.g., not requiring compliance with state open meetings laws). There is also reason to look closely at for-profit charter schools, which have produced worse outcomes than nonprofit charter schools and raise concerns about their compatibility with the public purposes of government-funded schools.

At the same time, the plan’s language is misleading in some respects and has bad ideas to accompany the good ones. In reality, relatively few charter schools are for-profit organizations (12% of all charter schools, educating 18% of all charter students). The Sanders plan suggests that charter schools have caused particular harm to communities of color. However, the most rigorous, large-scale studies of charter school effects find that urban charter school students perform substantially better than their matched peers in traditional public schools. (A related equity-based argument for charter schools is that they provide tuition-free choices to parents who can’t afford to buy into a school district they like.) Sanders’ plan also contains a vaguely worded call to curtail charter schools’ staffing autonomy (e.g., control over teacher hiring, tenure, and placement), which could severely limit the potential for charters to offer meaningfully different alternatives to district schools. Moreover, while questions about how charter schools affect other schools are difficult to answer empirically, evidence that charters harm other students’ performance remains limited.

Shifting views yield opportunities and risks

The politics of charter schools are changing. Charters are becoming more polarizing, both across parties and within the Democratic Party. The increasing skepticism among white Democrats could prove beneficial if it leads policymakers, especially at the local and state levels, to fix problems in their charter school laws and processes, whether those problems relate to transparency, accountability, or any other issue. However, if the Sanders announcement portends a broader, more aggressive push against charter schools, Democrats must take care to do this “with” and not “to” the communities that would be most affected by those changes.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).