This chapter is part of USMCA Forward 2024.

The USMCA introduced a novel chapter on digital trade. Digital trade refers to all forms of commerce conducted by electronic means, whether it be buying a good, selling a service, or accessing information.1 The value of trade in digitally ordered goods and services across the three North American economies could be as high as $250 billion yearly.2 Such trade requires cross-border data transfers. The importance of these transfers includes, for example, businesses across North America using data to streamline inventories, operations, and forecast demand, which are essential foundations for resilient supply chains. Or medium-sized companies adopting and integrating digital technologies like cloud computing and artificial intelligence (AI) into manufacturing processes, improving productivity, and creating new opportunities for regional trade.3 These economic and trade opportunities highlight the importance of the USCMA’s digital trade chapter. More recently, given geopolitics and emerging digital challenges, all three partners are stepping into regulating aspects of their digital economy. In this new regulatory-push context, Chapter 19 of the USMCA, the foundation of the North American approach to regulating digital trade, could help ensure that data flows between countries will not be unnecessarily restricted.

USMCA digital trade chapter: What has changed since it came into force?

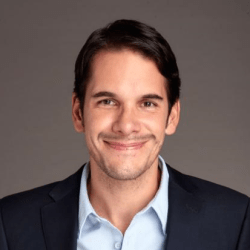

The USMCA’s Chapter 19 on digital trade provides a foundation for better cooperation on integrating North American digital markets. It includes important commitments to cross-border data flows, avoiding data localization requirements, and not requiring access to source code as a condition for market entry (along with exception provisions for legitimate public policy objectives, such as privacy, consumer protection, and national security concerns). This USCMA chapter also supports digital trade by, for example, prohibiting customs duties on electronic transmissions (see table below). More broadly, the chapter creates regulatory stability, encouraging data-driven business models relying on cross-border data flows. The United States International Trade Commission on the digital trade chapter found: “USMCA represents an insurance policy that data flows within the North American economic space will continue to be unrestricted.”4 However, since the agreement came into force, governments are increasingly regulating the digital economy, potentially creating restrictions to cross-border data flows that could hinder digital trade opportunities.

On the one hand, several governments are creating barriers to data flows amid privacy and national security considerations.5 On the other hand, within North America, debates begin as to whether some of the USMCA digital trade commitments are aligned with the new push for regulation. For example, the USMCA commitment on content moderation6 is being questioned in the U.S., Canada, and other jurisdictions7 as the way forward. Also, the United States administration is reviewing its support for rules allowing free cross-border data flows, prohibiting national requirements for data localization and reviewing software source code at the World Trade Organization, as these commitments–all reflected in the USMCA–might have impacts on the U.S. government space to pursue domestic policies like antitrust, consumer protection, and AI regulation.8

The following outlines key regulatory challenges on cross-border data flows and how these might impact the USMCA going forward.

AI regulation

Governments worldwide are discussing policies and regulations against perceived negative consequences of AI, such as biases and discrimination, security risks, privacy and misinformation, and copyright infringements.9 Different regulatory approaches are emerging globally, yet all efforts seek trustworthy, transparent, and accountable AI models.10 The European Union (EU), for example, recently agreed on the first-ever legislation to regulate AI.11,12 The proposed “AI Act” includes safeguards on general purpose artificial intelligence, obligations for AI models categorized as “high risk”, and sanctions for noncompliance.13

In the U.S., in July 2023, the Biden administration secured voluntary AI commitments by seven leading AI companies14 on (1) safety: establishing AI products are safe before public introduction, conducting rigorous testing and public disclosure of AI assessments; (2) security: building systems resilient to cyber threats; and (3) trust: ensuring authenticity of AI-generated content, preventing bias, protecting privacy, and shielding children. Building on these voluntary agreements, months later President Biden signed an Executive Order to establish security and privacy protection standards, requiring AI developers to safety test new models and share results with the U.S. government, to help ensure AI systems are safe, secure, and trustworthy.15 The Canadian government has proposed the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act to address systemic risks during design and development of AI systems. Additionally, in September 2023, the Canadian Ministry of Innovation, Science, and Industry announced a voluntary code of conduct on the development and management of generative AI, which “temporarily provides Canadian companies with common standards and enables them to demonstrate, voluntarily, that they are developing and using generative AI systems responsibly until formal regulation is in effect.”16 The Mexican government is not formally discussing the issue. In the Mexican Congress, however, the “Law for the Ethical Regulation of Artificial Intelligence and Robotics” was introduced in May 2023 to regulate AI through a new decentralized body, the Mexican Ethics Council for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics. But progress on this law is uncertain.

Related to these regulatory efforts, the USMCA’s commitment to not requiring source code access as a condition for trade could raise concerns on potential limits to government scope on developing and enforcing appropriate AI regulation. Would individual country efforts to regulate AI, including enforcement actions, be inconsistent with trade commitments over algorithmic source code? Or is it allowed under the exceptions provision? Moreover, the diverse approaches that could emerge across North America raise the question of how to use the USMCA for cooperation on AI regulation.17 AI’s dependence on massive datasets, for example, highlights the importance of Chapter 19’s free data flow commitments. Going forward, should there be a North American approach to AI? Should AI cooperation be prioritized in USMCA meetings? Must the USMCA be amended to include specific AI commitments18?

Cybersecurity

The USMCA includes commitments for closer cooperation on cybersecurity matters to mitigate intrusions or dissemination of malicious code and share best practices. Robust cybersecurity measures enhance digital trade by further strengthening supply chain resilience and securing critical infrastructure operations for trade, including electricity generating facilities, airports and ports, and customs operations, among others. None of the three countries have a comprehensive federal law regulating cybersecurity; however, since USMCA’s enactment all have initiated domestic efforts to tackle such concerns internally. According to the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, in the top 20 countries most victim to cyberattacks, the U.S. is at one, Canada at two, and Mexico at nine.19

In the United States, cybersecurity is governed by a patchwork of regulatory frameworks. These include sector specific regulations (e.g., the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act or the Financial Services Modernization Act Gramm-Leach), state privacy and cybersecurity legislation that regulates data breaches notifications, federal agencies using rulemaking power to regulate aspects of it (like the Securities Exchange Commission material disclosure of information to businesses cybersecurity policies or the Transportation Security Administration efforts on cyber-securing all modes of transportation), and national security law.20 Recently, the Biden administration has signaled this patchwork of laws and regulations has resulted in inadequate and inconsistent outcomes and called for a revamp of the federal cybersecurity framework.21 Proactively addressing cybersecurity challenges, the Administration released a National Cybersecurity Strategy,22 which provides a vision for the type of cybersecurity work the federal government will be pursuing.

In Canada’s case, it has actively enhanced its cybersecurity framework through key initiatives and legislative actions. Like the U.S., this approach is governed by a combination of laws, policies, and strategies rather than a single, dedicated federal cybersecurity law. Key elements of the framework include a National Cyber Security Strategy, the Digital Privacy Act (setting rules for private sector handling of personal information in commercial activities), the Cyber Incident Management Framework (to improve Canada’s response to cyber incidents), Communications Security Establishment Act (for better interception and disruption of foreign cyber threats), and the Anti-Terrorism Act and the Criminal Code of Canada (including provisions relating to cyber terrorism and cybercrime).

In Mexico, increasing cyberattacks highlights the need for a more robust Mexican cybersecurity framework, especially when government institutions like the oil and gas company, tax administration office, national water commission, and recently, defense ministry, have been under attack.23 Some laws and regulations include the concept “information technology security” (e.g., the Mexican Federal Criminal Code–articles 211 BIS I to 211 BIS 7–sanctions illicit access to computer systems and equipment).24 However, they are not part of a coherent effort for preventive and corrective measures that should be taken against a cybercrime. More recently, a cybersecurity law initiative presented to Congress by Congressman Javier Lopez Cassarin has been under discussion.25 This law aims to establish a national cybersecurity system, a legal and operational framework for new federal cybersecurity institutions, including a national agency and the National Cybersecurity Council for coordinating cybersecurity efforts across different government agencies.26 It also contemplates criminalizing cyberattacks and conducting annual penetration testing at public and private institutions. Despite its significance, the proposal has faced criticism, particularly concerning potential human rights violations, and as such, has stalled.

As for North American cooperation on cybersecurity matters, in August 2022, the U.S. and Mexico convened a bilateral cyber dialogue for cooperation on a “shared commitment to an open, interoperable, secure, and reliable” cyberspace.27 It was a first, and so far, the only one of its kind. However, representatives from all three countries have convened several times through deputy-level meetings to discuss and advance shared priorities, including trade flow cooperation in emergencies, touching upon cybersecurity.28 In line with USMCA’s Article 19.15 commitment to closer cooperation on cybersecurity, these meetings could set the stage for future collaborations to solidify an aligned approach to domestic cybersecurity frameworks.

Export control

In recent years, U.S. cybersecurity concerns have shifted from terrorism to China, either from cyberattacks by the Chinese government and/or the potential use of Chinese information technology firms as espionage platforms. In this context, and amid heightened technological rivalries over technologies like Artificial Intelligence, 5G, Internet of Things and microchips, the U.S. is restricting the exports of, and investments in, key technologies such as critical hardware, semiconductors, and communications platforms to that country. Of notice is the semiconductor ban of 2022 and its recent update in October 2023. The U.S. Department of Commerce’s export controls not only prohibits U.S. exports of semiconductors to China but includes a list of related items that could be used in the semiconductor’s supply chain technology in that country.29 These shifting U.S. concerns over access by the Chinese government to critical technologies raises questions as to what the U.S. will expect of its USMCA partners. For example, will the U.S. presume, for regional security objectives, similar export controls be implemented by Canada and Mexico when it comes to China? The USMCA does not address export controls, an issue typically excluded from trade agreements and instead dealt with as a national security issue. However, the merging of trade and security issues raises the question of whether there is a future role for the USMCA in aligning approaches to the more expansive export controls that the U.S. has developed in recent years.

Data privacy

Another potential conflict area for North American partners is if future domestic reforms to privacy laws modify the treatment of cross-border information flows. Data privacy legislation generally aims to secure consumers data privacy, especially personally identifiable information. The U.S. does not have a comprehensive federal privacy law, but a patchwork of sectoral, federal, and state regulations. Currently, 13 U.S. states have enacted comprehensive privacy laws, drawing on the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).30 The GDPR’s standard on cross-border data transfers is that businesses are not allowed to transfer personal data outside the EU unless “adequate” measures for protection exist.31 Presently, U.S. state privacy laws have no such cross-border restrictions. Instead, entities collecting personal data are responsible for complying with their published privacy policies. The U.S. Congress could eventually consider the need for a comprehensive federal data privacy legislation, which could include handling standards for cross-border information flows.32 The latest attempt for a federal privacy law was the American Data Privacy Protection Act (ADPPA), introduced May 2022 with a congressional hearing on the subject in April 2023.

The pace of change, the economic and trade importance of data, and the use of digital technologies, combined with potential divergent regulation, underscores the need for regular and sustained dialogue on these issues.

Canada’s federal privacy law does not contain specific provisions on cross-border data flows.33 Similar to the U.S., any business is free to transfer any type of personal data to other organizations, nationally or internationally, and is responsible for personal information in its possession or custody. This includes information to a third party for processing. In 2022, the Canadian government proposed the Digital Charter Implementation Act (a reintroduction of a proposed 2020 legislation), which includes a revision of the country’s federal privacy law in line with the GDPR but without cross-border flow restrictions. The original bill specifically mentioned that rules governing the protection of personal information should recognize “an era in which data is constantly flowing across borders and geographical boundaries and significant economic activity relies on the analysis, circulation, and exchange of personal information,”34 so it does not distinguish between transfers within Canada or internationally. If approved in its current form, the default position will be for free data flow across borders. In Mexico, the federal privacy law also does not contain specific provisions on cross-border data flows. In general, data subjects need to be informed of personal data transfers in a privacy notice and consent is required. No relevant discussions on modifying the Mexican privacy law seem to be on the public’s mind.

As such, for now, the approach to data privacy for cross-border data flows between the three countries is aligned and supportive of digital trade. If divergent approaches were to appear, data flow could still be possible. For example, the new EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework (DPF) builds interoperability between legal systems to enable the free flow of data despite differing data privacy regimes.35 Agreements of this type can only be possible through dialogue and trust, highlighting the importance of cross-partner cooperation mechanisms (or forums) on high tech and digital economy issues (in this case, the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council).

The above-mentioned potential areas for different approaches to digital regulation are not intended to be exhaustive,3636 but rather examples of future challenges and opportunities in the North American region. The pace of change, the economic and trade importance of data, and the use of digital technologies, combined with potential divergent regulation, underscores the need for regular and sustained dialogue on these issues. Through a permanent institutionalized council or forum, partners could discuss how to handle possible USMCA digital trade commitment divergences. For example, for dealing with concerns that arose from Mexico’s possible USMCA infringement on data location restrictions on fintech businesses in 2021,37 or Canada’s proposed digital services tax that would require personal and transactional information of Canadian users of digital services to be stored within Canada for tax assessment purposes.38 Such potential divergences will keep arising amid changing geopolitical, tech, and regulatory landscapes.

Chapter 19 going forward

So far, there has been no formal USMCA dispute on digital issues. However, dispute settlement should be a last resort, and instead, goals of harmonizing digital regulation or achieving regulatory interoperability should be the focus. Making progress here will require more intensive engagement across the three governments. Securing future data flows does not necessarily require the harmonization of North American laws and regulations; still, it does require common principles on privacy, security, intellectual property, and a high degree of trust. As the G7 recently declared, while the means to trustworthy AI may vary, there is a need to identify “commonalities, complementarities, and elements of convergence between existing regulatory approaches and instruments enabling data to flow with trust, in order to foster future interoperability.”39 Like the cross-border data flow agreement between the U.S. and EU, operationalizing this cooperation to a shared agreement is largely a matter of institutionalizing discussions. The G7, for example, has a working group led by countries’ Digital and Tech Ministers. Other international forums on digital issues have seen involvement of different government departments, from security to trade and digital ministries.

However, dispute settlement should be a last resort, and instead, goals of harmonizing digital regulation or achieving regulatory interoperability should be the focus.

What institutional mechanism could the three USCMA governments rely on if/when differences arise? The USMCA’s Chapter 19 calls upon Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. to exchange information and share experiences on regulations and policies relating to digital trade and enjoins the countries to establish “a forum”. This North American digital trade forum could be integrated by the Department of Commerce (U.S.), Innovation, Science and Economic Development (Canada), and Secretaria de Economía (Mexico).40 Similarly, the recently launched North American Ministerial Committee on Economic Competitiveness (NAMCEC), seeking to align efforts on regional competitiveness in future industries, could be the forum.41

The U.S. and Canada have experience participating in international digital issues discussions, Mexico less so. In Mexico, aspects of the country’s digital space fall under the guide of several government bodies, some like telecoms, antitrust, and privacy regulators that are autonomous of the Executive branch. Cooperation among all regulatory bodies involved in the digital space is incipient, in part because of lack of support from the federal government for respective regulators’ work. This raises the challenge for Mexico to coordinate its approach to digital policy and cooperation with its North American partners. In 2024, the Mexican president could contemplate an administrative restructure of the federal government and create a Ministry of Digital Affairs.

What issues related to digital trade could be dealt with in such a North American forum? Regarding cross border data flow, for example, the G7 plan lays out the following areas of cooperation: (1) data localization; (2) regulatory cooperation; (3) government access to data; (4) data sharing for priority sectors; and (5) fostering future digital regulatory interoperability.42 In other substantive issues, there is semiconductor manufacturing mapping, small- and medium-sized enterprises digitalization, promoting digital skills development, tech talent mobility, fostering new players in cross-border payment services, incentivizing investment in robust digital infrastructure, among others.

Looking beyond specifics, the point here is the need for deeper cooperation on digital issues. On regulatory aspects, the general purpose of such collaboration should be interoperability across North America while accommodating each partner’s legitimate public policy and national security objectives.

Related viewpoint

More from USMCA Forward 2024

-

Footnotes

- The OECD Handbook on Measuring Data Trade defines digital trade as all trade that is digitally ordered and/or digitally delivered.

- Patrick Leblond, The USMCA and digital trade in North America in “USMCA Forward 2022: Building a more competitive, inclusive, and sustainable North American Economy,” Brookings Institution (Feb 28, 2022).

- For more details on the content of USMCA Chapter 19 and on the potential of digital trade in the region see Patrick Leblond (Feb 28, 2022) and Miranda Alamilla and Gabriel Cabañas, Digital Trade under the USMCA: A Modern Opportunity for North American Economic Growth, Wilson Center (March 21, 2022).

- Dan Ciuriak, Optimizing North American Supply Chain in Critical Technologies: The USMCA Digital Advantage in “USMCA Forward 2023: Building a more integrated, resilient, and secure supply chains in North American Economy,” Brookings Institution (Feb 2023), p. 90.

- For a compressive explanation on national policy considerations and international tensions on the rules regulating digital trade and cross border data flow see Frank Schweitzer, Ian Saccomanno and Naoto Saika, The Rise of Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, and the Next Generation of International Rules Governing Cross-Border Data Flows and Digital Trade (Sept 14, 2023), https://www.whitecase.com/insight-our-thinking/rise-artificial-intelligence-big-data-next-generation-international-rules.

- This prohibition was modeled on the Digital Millennium Copyright Act’s Section 512, protecting digital platforms for liability for the actions of their users, see Anupam Chander, The Coming North American Digital Trade Zone (Oct 9, 2018), https://www.cfr.org/blog/coming-north-american-digital-trade-zone.

- Anu Bradford, After the Fall of the American Digital Empire, 23-10 Knight First Amend. Inst. (Sept. 21, 2023), https://knightcolumbia.org/content/after-the-fall-of-the-american-digital-empire.

- Reuters, “US drops digital trade demands at WTO to allow room for stronger tech regulation” (October 25, 2023), https://www.reuters.com/world/us/us-drops-digital-trade-demands-wto-allow-room-stronger-tech-regulation-2023-10-25/.

- Joshua P. Meltzer, Toward International Cooperation on Foundational AI Models. An Expanded Role for Trade Agreements and International Economic Policy, Brookings Institution (November 2023), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/toward-international-cooperation-on-foundational-ai-models/.

- Sebastian Vos, Carl Bildt, Cecilia Malmstrom and Bart Szewczyk, Series on Global AI Policy — Part I: European Union, Covington Global Policy Watch (Oct 4, 2023), https://www.globalpolicywatch.com/2023/10/spotlight-series-on-global-ai-policy-part-i-european-union.

- See press release available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20231206IPR15699/artificial-intelligence-act-deal-on-comprehensive-rules-for-trustworthy-ai.

- The agreed text will now have to be formally adopted by both Parliament and Council to become EU law. Parliament’s Internal Market and Civil Liberties committees will vote on the agreement in a forthcoming meeting.

- Ibid.

- Amazon, Anthropic, Google, Inflection, Meta, Microsoft, and OpenAI.

- The White House, “Fact Sheet: President Biden Issues Executive Order on Safe, Secure and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence” (October 30, 2023).

- Information available at https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/innovation-better-canada/en/artificial-intelligence-and-data-act.

- More broadly, commitments in USMCA on regulatory transparency and due process provide an important opportunity for regulators in each country to learn about the trade impacts of proposed AI regulation.

- The New Zealand-U.K. Free Trade Agreement, which came into force in May of 2023, includes a commitment to account for principles and guidelines of relevant international bodies like the OECD and the Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence when developing each parties AI governance frameworks. In contrast with binding commitments, the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) signed on 2020 between New Zealand, Chile, and Singapore, contains an AI Governance Frameworks, which is, more than anything, a general statement that trading partners will promote the adoption of this technology taking into consideration internationally recognized principles or guidelines.

- See “Federal Bureau of Investigation Internet Crime Report” (2022), p. 19, available at https://www.ic3.gov/Media/PDF/AnnualReport/2022_IC3Report.pdf

- See James X. Dempsey “Cybersecurity Law Fundamentals” (2021) for more details on the body of law that “result i[n] a patchwork” governing cybersecurity.

- The White House, “National Cybersecurity Strategy” (March 2023), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/National-Cybersecurity-Strategy-2023.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Mexico Daily News, “Mexico is one of the top victims of cyberattacks in Latin America” (December 27, 2002), available at https://mexiconewsdaily.com/news/mexico-top-victim-of-cyberattacks/.

- The Federal Telecommunications and Broadcasting Law (LFTR), the Federal Standard of Transparency and Access to Public Information (LFTAIP), the Federal Copyright Law (LFDA), the Federal Law on Protection of Personal Data Held by Private Parties (LFPDPPP), and the Federal Penal Code (CPF).

- The bill is currently being assessed in the Chamber of Deputies in the United Commissions of Citizen Security and Science, Technology, and Innovation.

- Key aspects of the proposed law include: (1) the creation of a National Cybersecurity Agency (NCA) and a specialized cybercrime prosecutor’s office; (2) granting cybersecurity powers to the Ministry of National Defense and the Ministry of the Navy; (3) appointment of specialized judges in the area of cybersecurity, and (4) obligations for private parties, including the notification of cybersecurity incidents and the presence of a legal representative in Mexico.

- See https://www.state.gov/joint-statement-on-u-s-mexico-working-group-on-cyber-issues/.

- For example: “First USMCA Deputies Meeting” at https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2022/january/mexico-united-states-and-canada-joint-statement-first-usmca-deputies-meeting: “Second USMCA Deputies Meeting” at https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2023/january/united-states-mexico-and-canada-joint-statement-secondusmcacusmat-mec-deputies-meeting; or “Second USMCA Free Trade Commission Meeting” at https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2022/july/joint-statement-second-meeting-usmcacusmat-mec-free-trade-commission.

- Center for Strategic and International Studies, “Insight into the U.S. Semiconductor Export Control Update” (Oct. 20, 2023), available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/insight-us-semiconductor-export-controls-update.

- US state laws with comprehensive approaches to governing the use of personal information: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Montana, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia. See National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), https://www.ncsl.org/technology-and-communication/2023-consumer-data-privacy-legislation.

- The EU has so far has recognized 14 countries that provide adequate data protection, including Canada and more recently the U.S. (see EU Adequacy decision for more details).

- See US Federal Privacy Legislation, available at https://iapp.org/media/pdf/resource_center/us_federal_privacy_legislation_tracker.pdf.

- Data Protected – Canada, last updated June 2022, https://www.linklaters.com.

- Bill C-11, Purpose provision. In November 2020 the federal government introduced the bill, although it never made it into law. Then, on June 2022, it introduced Bill C-27, titled the Digital Charter Implementation Act, which retains the core elements of Bill C-11.

- The new DPF enables US industries to comply with EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) while being subject to US laws relating to foreign intelligence surveillance, see Frank Schweitzer et al., Sept 14, 2023.

- As previously mentioned, another example is on content moderation: in the US calls to reform Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act have increased. If Canada eventually regulates on it or the US Congress eventually decides to modify Section 230, will it be also necessary to remove this provision from the USMCA?

- https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5610487&fecha=28/01/2021#gsc.tab=0

- Department of Finance Canada, Digital Service Tax Act, https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2021/12/digital-servicestax-act.html.

- G7 Digital Ministers’ Track – Annex 1 in “G7 Action Plan for Promoting Data Free Flow with Trust” (April 30, 2023), https://bmdv.bund.de/SharedDocs/DE/Anlage/K/g7-praesidentschaft-final-declaration-annex-1.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

- Patrick Leblond (March 21, 2022).

- Joshua P. Meltzer, Earl Anthony Wayne, and Diego Marroquín Bitar, USMCA at 3: Reflecting on impact and charting the future, Brookings Institution (July 19, 2023), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/usmca-at-3-reflecting-on-impact-and-charting-the-future.

- See “G7 Action Plan for Promoting Data Free Flow with Trust.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).