This viewpoint is part of USMCA Forward 2024.

In March last year, I received a call from the office of the governor of the Mexican state of Nuevo León, Samuel García, who invited me to a newly formed economic advisory council. He was excited to learn that Softtek, the company I lead, had coined and trademarked the term “nearshore” in the 90s.

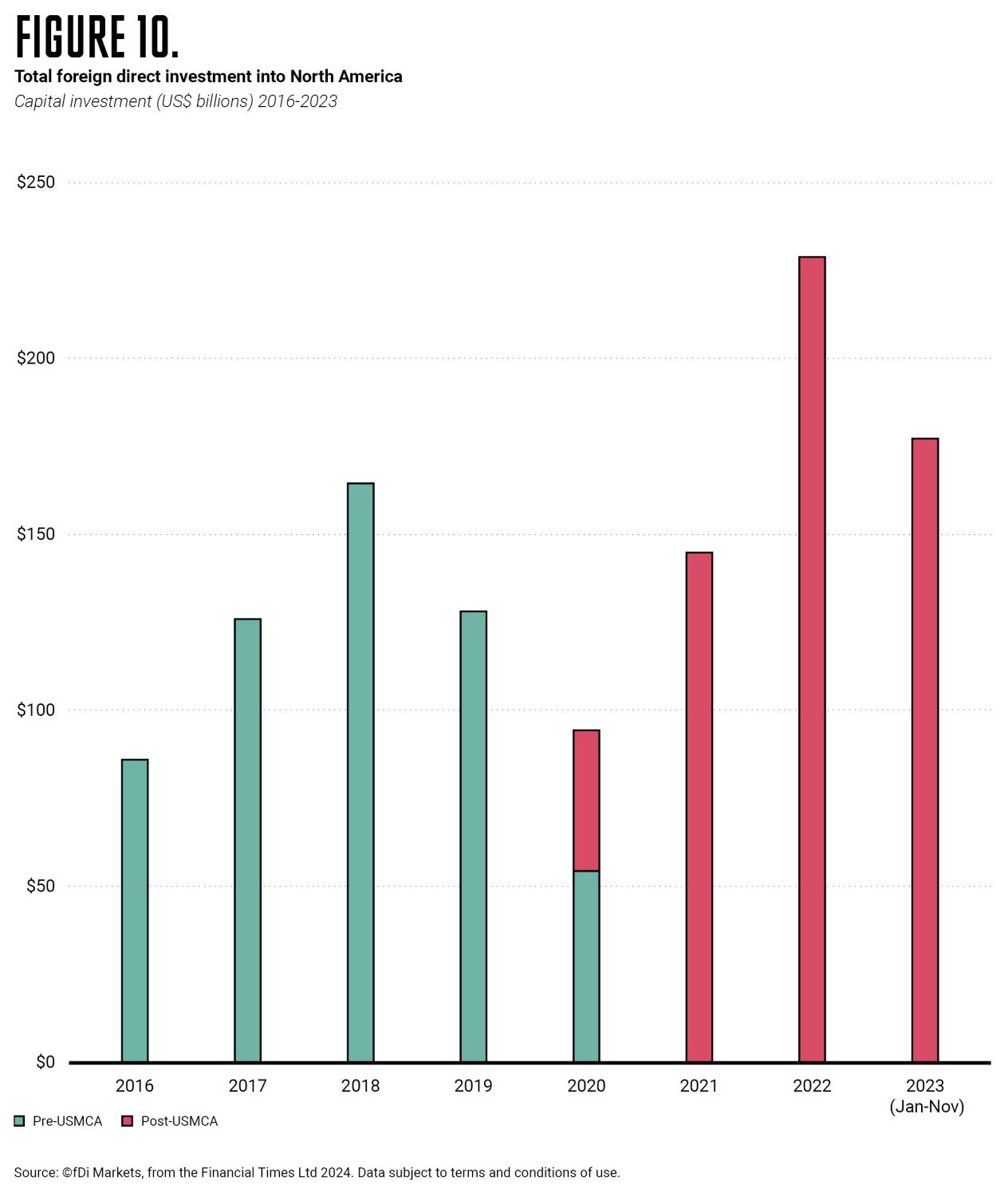

Governor García, like many leaders in Mexico, is a proponent of nearshoring, the form of outsourcing of services delivered from a nearby location. This contributed in part to $29 billion in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Mexico during the first half of 2023—a 41% increase from 2022 according to the Ministry of Economy1—which, according to Morgan Stanley, can take Mexican manufacturing exports from $455 to $609 billion in the next five years.2 Governor García’s enthusiasm was also fueled by Tesla’s recent announcement to open a factory in Nuevo León, which is set to produce vehicles in 2026, affirming Mexico’s nearshoring boom.

The adoption of the nearshore brand over 20 years ago by a Nuevo León-based company for exporting IT services to the U.S. was seen as visionary by the governor.

The true visionaries, however, were the tri-national teams behind NAFTA in 1992. The USMCA, as the successor to NAFTA, is now three years old. Since coming into force, USMCA has significantly contributed to Mexico’s post-COVID recovery, supporting growth in Mexican exports with the result that Mexico is now the United States’ primary trading partner.

In addition to supporting growth in North American trade, I want to highlight three additional ways that USMCA has been successful:

- Reducing U.S. dependence on China while setting the stage for the nearshoring boom that has allowed Mexico’s post-COVID recovery.

- Introducing a chapter on digital trade, which was non-existent in the early 90’s and not covered by NAFTA.

- Including a six-year review requirement that can be used to keep USMCA up to date and relevant.

Adaptations should be welcomed.

Focused on digital trade, Chapter 19 of the USMCA includes definitions and rules for aspects like algorithms, digital products, computing facilities, electronic authentication, and signatures—important aspects of modern business and consumer life. Yet, the chapter lacks explicit mention of Artificial Intelligence (AI), highlighting how rapidly technology is affecting trade and investment relations.

We are already used to ChatGPT4, to answer trivial questions, brainstorm, or as an “intern” to lighten the load. And as a reminder, it was launched semi-recently in November 2022. This transformative technology has taken the world by storm, prompting the Biden-Harris Administration’s AI Bill of Rights, and Executive Order on AI, directing agencies to combat algorithmic discrimination while enforcing existing authorities to protect people’s rights and safety.

AI is impacting many facets of trade and business, including copyright and labor, as shown during the 2023 strikes of the Writers Guild of America, Screen Actors Guild- American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA), and the United Auto Workers (UAW)—all of which demanded actions restricting negative impacts of AI. The USMCA should be updated to include new commitments to cooperate on AI. The USMCA commitments on cybersecurity in article 19.15 can inspire the design of cooperation on AI:

- The Parties recognize that threats to cybersecurity undermine confidence in digital trade. Accordingly, the Parties shall endeavor to:

- Build the capabilities of their respective national entities responsible for cybersecurity incident response; and

- Strengthen existing collaboration mechanisms for cooperating to identify and mitigate malicious intrusions or dissemination of malicious code that affect electronic networks, and use those mechanisms to swiftly address cybersecurity incidents, as well as for the sharing of information for awareness and best practices.

The article concludes by encouraging parties to embrace risk-based approaches rather than restrictive regulations. A similar path should be followed regarding AI.

More than just trade.

On December 17, 2023, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection ordered a temporary closing of the two largest cargo rail bridges at El Paso and Eagle Pass. The measure was attributed to the need to reallocate resources amid migrant surges.

Similarly, Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s orders for cargo truck inspections at all state border crossings disrupted supply chains and prompted Mexico’s foreign ministry to call for the U.S. government to “mediate with Texas to stop the exhaustive inspections of cargo trucks carried out by the Texas Department of Public Safety.”3

Regardless of the motivations— national security or political posturing—the migrant crisis is real and must not be overlooked in a trade deal as significant as the USMCA.

A broader perspective, beyond trade, in the USMCA is crucial, acknowledging social mobility challenges in Mexico unmet by NAFTA and USMCA.

It is time to bring brilliant minds and goodwill to develop the right policies, incentives, and structures to foster wellbeing in the USMCA. But that is just a start; delivering on the promise of social mobility falls squarely on the Mexican business community.

Access to the largest and wealthiest consumer market in the world should come with the responsibility to create sustainable businesses; they must be more than opportunistic initiatives with short-term gains.

The USMCA must evolve into a trade agreement with a humanistic approach—emphasizing social responsibility, inclusion, and long-term business development for a prosperous North American future.

-

Footnotes

- Secretaría De Economía, “México Recibió 29 Mil Millones De Dólares De Inversión Extranjera Directa Durante El Primer Semestre De 2023,” gob.mx, n.d., https://www.gob.mx/se/prensa/mexico-recibio-29-mil-millones-de-dolares-de-inversion-extranjera-directa-durante-el-primer-semestre-de-2023?idiom=es.

- Morgan Stanley, “Mexico Rides Nearshoring Wave | Morgan Stanley,” n.d., https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/mexico-nearshoring-gdp-growth.

- https://www.reuters.com/world/us/mexico-calls-end-texas-cargo-inspections-governor-complicating-migration-2023-10-10/.

Commentary

The potential of nearshoring in North America: The case of Mexico

March 6, 2024