This chapter is part of USMCA Forward 2024.

Under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) review clause, on July 1, 2026, the U.S., Mexico, and Canada will confirm in writing whether or not to continue the agreement. If one or more of the three parties decide to take the step of not renewing the agreement, it will kick off a process that will leave the future of the USMCA in a state of uncertainty for years to come. That is, unless the objecting party or parties change their mind. Even though the six-year review is still more than two years away, the uncertainty provided by the review clause is already a significant preoccupation for the business communities in all three countries.

Where did the review clause come from? What is the review clause? What are the prospects for the review? The following lays out a possible path forward.

Why a review clause?

The U.S. proposal in the USMCA negotiations for a review clause was unique and unprecedented. One of the central tenets of free trade agreements is that they are intended to bring security and predictability to the trading relationship between the parties, and a provision that provokes ongoing uncertainty about the continuity of the agreement raised questions and concerns when it was introduced.

The U.S. has used two main arguments in support of the review clause: 1) the clause would provide the U.S. with leverage to make ongoing changes to the agreement and 2) it would force politicians to address difficult decisions rather than delay confronting them. On the first point, the U.S. Trade Representative during the Trump Administration, Robert Lighthizer, wrote that “we wanted a paradigm-changing agreement that would not only address current trade irritants but prevent the United States from ever again finding itself saddled with an unbalanced, outdated agreement and with no leverage to change it other than the costly and disruptive threat of outright withdrawal.”1 Similarly, Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law and Senior Adviser to the President during the negotiations, asserted that “…it is imperative that the U.S. retain leverage in any of our trading relationships to prevent unfair trade practices and market distortions and correct them when they occur. The sunset provision will give us just that.”2

Lighthizer and Kushner have also argued that the review clause would be a means to put pressure on politicians to confront issues in the agreement with Kushner arguing that it would “force politicians to confront difficult issues and changing dynamics rather than kick the can down the road.”3

The U.S. proposal for a review clause was widely criticized after it became public. The business community, various think tanks, news media, and several Republicans (Paul Ryan, Pat Toomey, Bill Cassidy, and others) were strongly critical of the review clause and the negative impact they felt it would have on business confidence.

Trade agreements historically have always been intended to last indefinitely, although parties are usually free to withdraw unilaterally without penalty or restrictions if desired. The original North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) included a withdrawal provision (Article 2205) that followed the standard model that allows a party to withdraw from the agreement six months after providing written notice to the other parties. This provision has been replicated in the USMCA (Article 34.6) in essentially the same terms.

Both the original NAFTA (Article 2202) and the USMCA (Article 34.4) also contain similar provisions for amending the agreement. It has long been considered that provisions allowing parties to amend the agreement without restriction and enabling parties to withdraw from the agreement provided sufficient flexibility to allow for agreements to evolve over time or be terminated if it was no longer in the parties’ interest to continue it.

The original U.S. proposal for a review clause was that the USMCA would have a fixed term and would terminate after four years. Canada and Mexico rejected the initial proposal outright, arguing that an agreement intended to last only four years with no assurance of an agreement beyond that was of little value and offered the private sector no confidence for future planning, growth, or investment. The review clause became one of the most contentious issues in the negotiations, and the U.S. came back with several modifications, eventually settling on the review clause in its current form. Canada and Mexico continued to dislike the review clause, but eventually conceded to it as part of the overall package to conclude an agreement.

What is the review clause?

The USMCA review clause in article 34.7 contains only limited direction. In summary, USMCA will terminate 16 years after the date of its entry into force (i.e., by 1 July 2036), unless each party confirms that it wishes to continue the agreement for a new 16-year term. The parties are to confirm their ongoing support for USMCA at a “joint review” by the Free Trade Commission (the Commission) which comprises Minister-level government representatives from each party. The first joint review is to take place on the sixth anniversary of entry into force of USMCA—which will be on July 1, 2026. At the joint review, the Commission will review the operation of USMCA. The Commission can also “review any recommendations for action submitted by a Party, and decide on any appropriate actions. Each Party may provide recommendations for the Commission at least one month before the Commission’s joint review meeting takes place.”4 Should the parties confirm in writing that they want to continue with the USMCA, then the agreement will be extended for another 16 years. If the parties do not extend the agreement at the first joint review in 2026, then the Commission is to conduct a joint review each year for the remainder of the term of the agreement (i.e., until 2036). During these subsequent joint reviews, the parties can confirm in writing their wish to extend the agreement for another 16 years. Failure to extend the agreement during the first or subsequent joint reviews will lead to USMCA termination on July 1, 2036.

From a process perspective, the issue of the review clause is an ongoing topic of discussion in the regular meetings of the Commission in the lead up to the review. In the U.S., under the USMCA implementing legislation provisions on the Sunset Clause, the U.S. administration will be obliged to: consult appropriate congressional committees and stakeholders; provide its recommendations for actions to be taken at the review; and advise the committees of the position of the U.S. with respect to extending the term of the USMCA. The U.S. will need to report to the Congress on these issues at least 180 days before the joint review.

Politics matters

Adding uncertainty in the lead up to the six-year review, there will be national elections held in Canada, Mexico, and the United States prior to the review.

In Canada, the minority government Liberal Party and one of the opposition parties, the New Democratic Party (NDP), reached a confidence and supply agreement on March 21, 2022. This would have the NDP support the Liberal Party on confidence and budgetary matters until 2025, provided that an agreed list of issues are addressed.5 That agreement continues to hold, although an election could be held at any time.

All parties supported the passage of the USMCA implementation bill in Canada, and the agreement was widely supported by the business community, key labor organizations, and the majority of Canadians. Whether Canada is led by the Liberal Party or the Conservative Party (currently leading in the polls), there is little doubt that Canada will continue to support the continuation of the agreement. The Canadian government has made few public comments on the review to date, but the business community has highlighted the importance of a successful review. The Business Council of Canada has stated that: “[f]irst and foremost, our number one priority must be the renewal of the Canada-U.S.-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) when it comes up for review in 2026.”6

Mexico will hold a national election on June 2, 2024. Former Mexico City Head of Government Claudia Sheinbaum leads Morena, the ruling party of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and the Juntos Hacemos Historia coalition. Xóchitl Gálvez is the leader of the main opposition alliance of the National Action Party (PAN), the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), and the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD). In January of this year, Jorge Álvarez Máynez joined the presidential race from the Movimiento Ciudadano (MC) party.

Sheinbaum would be expected to continue the approach of President López Obrador while Gálvez would be expected to take a stronger position in support of the USMCA. Under any scenario, the reliance of Mexico on the U.S. market is expected to lead Mexico to support the continuation of the agreement, although the list of contentious issues is likely to be longer under a Sheinbaum administration than one led by Gálvez.

The U.S. election on November 5, 2024 is expected to be a rematch between current President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump. The Biden administration has said little about the review so far, but the U.S. Ambassador to Canada, David Cohen, stated in an interview on December 12, 2023, that “the U.S. is beginning to have our internal discussions about what we might like to talk about with Mexico and Canada as the sunset approaches.”7 According to the article, Cohen said “nobody is talking now about blowing up the deal.” Still, President Biden is expected to face pressure in the election to take positions against some USMCA issues, including Mexico on labor, energy, and agriculture issues, and possibly Canada on dairy, digital tax, and other issues.

Should former President Trump prevail, he will likely suggest that President Biden was not tough enough with Mexico and Canada and threaten to terminate the agreement if U.S. concerns are not addressed. It seems unlikely that a Trump administration—that pushed so hard for a review clause, and with the leverage the U.S. has as the much larger economy among the three parties—would pass up the opportunity to use the review clause to negotiate better terms.

The U.S. Congress is likely to express some views about the review as the date approaches, and the outcome of the elections in the House and in the Senate could have some influence on how much pressure they put on the administration over the review. Given that there is no formal approval role for Congress in the review process, however, the administration will make the final call. However, if amendments are made to the agreement as a result of discussions under the review, Congress would need to support those changes, so the role of Congress will continue to be important.

Whether the outcome of the 2024 election is a Democratic or Republican administration, it is likely that the U.S. will approach the review of the agreement with a list of issues on which it would be seeking agreement with Mexico and Canada. Overall, all three parties are beginning to prepare for a discussion in the lead up to the review, with the U.S. expected to be on offense, and Mexico and Canada mainly focused on trying to defend against any significant re-balancing of concessions.

Potential issues and outcomes

The joint review is a novel feature and has not been included in another trade agreement, as far as we are aware. As outlined, the U.S. wanted the joint review clause to push for changes to keep USMCA up to date while avoiding invoking the termination clause to motivate action. USMCA only somewhat achieves this as failure to agree to renew the agreement in 2026 still leaves 10 more years to reach agreement before USMCA terminates. In other words, the potential for termination remains but is pushed out to 2036.

Yet, a joint review is not needed for either party to pull out of USMCA or to propose changes to it. These are rights already recognized in the agreement. The question then is how to make the joint review a value-add process?

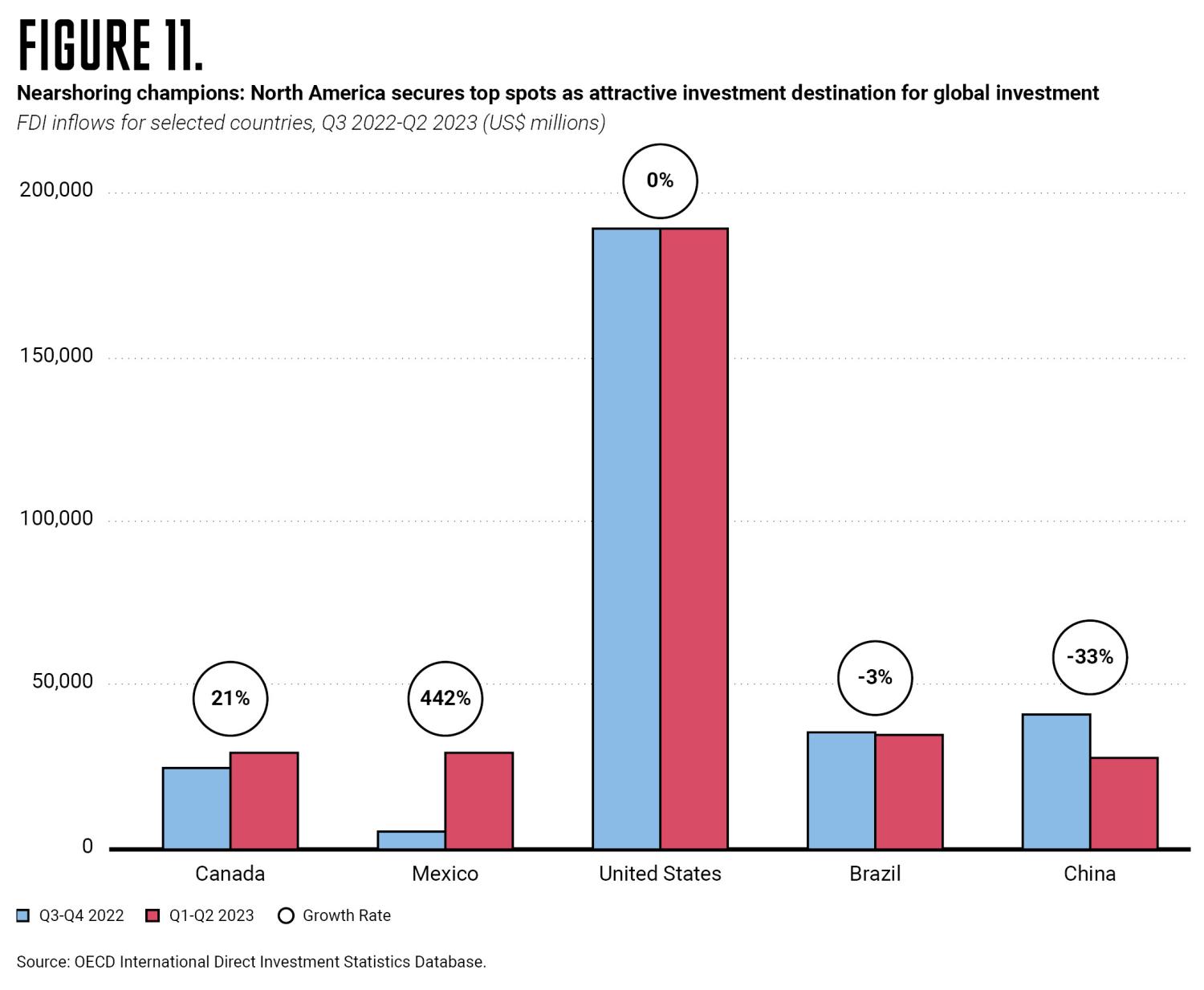

By increasing the odds that USMCA might terminate in 2036, investors would face greater risks and costs associated with cross-border trade and with making longer-term investments that will be needed in areas such as electrical vehicles (EVs), batteries, and semiconductors.

Keeping USMCA updated should be a goal that all parties can get behind. The USMCA provides only limited guidance, however, on how to do this. A starting point should be for all parties to approach the joint review as part of a longer-term investment in the ongoing health of North American economic relations by updating the agreement to keep it relevant. Failure to renew USMCA in 2026 would inject uncertainty into the future of USMCA, negatively affect trade and investment across North America, and signal a lack of commitment to the agreement. By increasing the odds that USMCA might terminate in 2036, investors would face greater risks and costs associated with cross-border trade and with making longer-term investments that will be needed in areas such as electrical vehicles (EVs), batteries, and semiconductors. The parties can avoid these costs and still turn the joint review into a productive process by agreeing to renew the USMCA in 2026 and at the same time, agree on a work program for addressing new issues in the USMCA and reporting back to the Commission. Immediate agreement to renew USMCA would signal ongoing commitment by each government to USMCA, while avoiding the uncertainty and economic costs that would follow from a failure to renew the agreement. However, the right of each party to leave under the agreement’s termination clause would remain as a spur.

To ensure that a joint review process remains focused on addressing new issues in USMCA, the parties should reach an agreement on the types of issues that should be part of a joint review. This could include improving operations at the border, strengthening supply chains, and/or facilitating trade in clean energy. There may be scope to address some of these issues by July 2026, whereas other issues may require longer-term attention and work.

Finally, the parties should also agree on the issues that should not be part of a joint review. Revising dispute settlement decisions by USMCA panelists that the losing party does not like would be a dangerous path to go down. For example, former U.S. Trade Representative Lighthizer in a November 2023 article addressed the USMCA panel finding on auto rules of origins (ROOs) that went against the U.S. and argued that “ Washington should announce immediately that it will demand a reversal of this decision during the sunset review.”8 We think this is wrong. Trying to change the outcomes of panel findings is at odds with the notion of a joint review as being about addressing new issues in USMCA, and instead would constitute a rebalancing of commitments and undermine what was agreed to in good faith by all three parties in the negotiations. Perhaps even more importantly, in addition to undermining faith in the dispute settlement process, trying to change dispute settlement outcomes at a joint review will make future implementation of adverse USMCA panel decisions by any USMCA party increasingly unlikely. This is because of the domestic pressures this will create on the losing government to renegotiate such panel decisions at a joint review. In other words, the U.S., by seeking a different outcome in the ROOs panel decision, would make it a lot less likely that Mexico would comply with an adverse ruling in the Biotech corn case that the U.S. has brought. More broadly, such an approach would undermine the certainty and value of USMCA commitments by politicizing dispute settlement outcomes and turning them into opportunities to renegotiate the deal.

Conclusion

Whatever the outcome of the U.S. election this year, the next U.S. administration is most likely going to seek changes to the USMCA as part of a joint review. In contrast, Canada and Mexico would prefer to retain the status quo and remove the threat of USMCA terminating in 2036 by having all governments agree to renew USMCA for another term. We have proposed a third way that builds on U.S. negotiators’ intentions with respect to the review clause by proposing that the joint review be the beginning of a process to address new issues in USMCA with an agreed agenda on a forward-looking workplan, a process that should be ongoing and subject to political oversight by reporting back to the Commission. We do, however, agree that as part of this, all parties should renew USMCA for another term in 2026. As we have outlined, renewing USMCA in 2026 would not prevent the U.S. or any government from threatening to withdraw from the agreement. From this perspective, our approach to the joint review aims to set up the process that will be needed to review USMCA. At the same time, our proposal avoids creating unnecessary—and what we believe are avoidable—costs and uncertainties for all countries. It will also prevent uncertainties for the economic prospects for the North American market and at the same help finalize ambitious outcomes.

More from USMCA Forward 2024

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).