The following is the introduction to the working paper “Toward a U.S.-Japan digital alliance” by Mireya Solís and published by the Sasakawa Peace Foundation as part of its Shaping the Pragmatic and Effective Strategy Toward China Project. The full paper can be found here. This project publishes working papers by U.S. and Japanese experts on the Sasakawa Peace Foundation’s International Information Network Analysis (IINA) website.

Introduction

The burgeoning digital economy presents an array of opportunities and challenges for the United States and Japan. Crafting international rules that sustain free and safe data flows, protecting infrastructure for advanced mobile communications, and solving supply chain shortages in the semiconductor industry are top priorities for policymakers in both countries. In pooling efforts to achieve these objectives, the United States and Japan have a chance to craft a digital alliance that modernizes their partnership as they adjust to the forces of technological shift, the pandemic shock, and geopolitical competition. The value proposition, however, rests on the ability of the United States and Japan to leverage bilateral cooperation to achieve a wider impact in disseminating far-reaching rules and standards and shoring up global value chains. Success in this endeavor will in no small measure shape how effectively the U.S. and Japan cope with the China challenge given China’s high-tech ambitions, its digital protectionism, and its growing influence abroad through initiatives such as the Digital Silk Road.

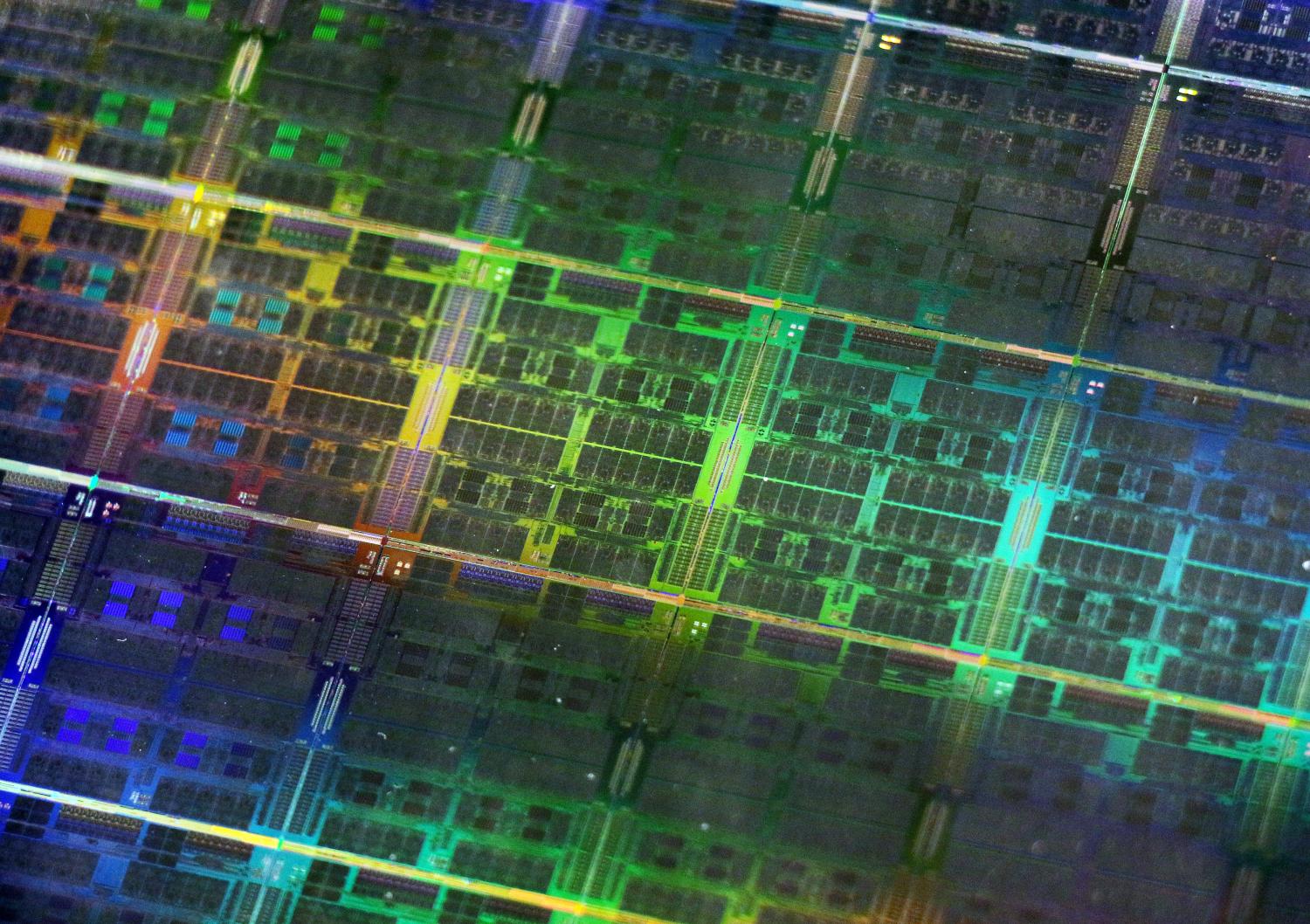

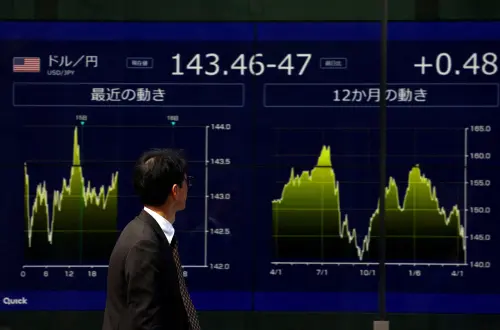

In pooling efforts to advance a shared digital agenda, the United States and Japan can bring to bear significant strengths. The United States ranks at the top of the world’s digital competitiveness index, is home to corporate giants in the information technology industry, and American semiconductor firms top global sales and lead in important production segments such as chip design and manufacturing equipment. While Japan’s dominant position in the semiconductor industry is a thing of the past, Japanese companies still enjoy dominant positions in key nodes of the semiconductor supply chain such as silicon wafers, advanced chemicals and manufacturing equipment. These chokepoint technologies are of increased relevance at a time of heightened tech competition and vulnerability. Moreover, Japan is at the forefront of codifying and disseminating rules and standards for the digital economy with a template that aligns with American priorities (i.e. the original and revised Trans-Pacific Partnership and the U.S.-Japan digital trade agreement), has set forth the Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT) initiative, and is a co-convener of World Trade Organization (WTO) e-commerce talks.

But allied coordination on digital policy and governance confronts significant challenges as each partner balances the benefits and risks of economic interdependence with China, opts for different implementation strategies, and incorporates its own domestic priorities. The analysis below explores tasks ahead in building a U.S.-Japan digital alliance around three pillars: advanced tech manufacturing (semiconductors), telecommunication platforms (5G and beyond), and international digital governance. These are not the only vital policy dimensions to the digital agenda (in fact, the docket is full and will continue to grow in areas such as AI, cybersecurity, etc.), but they do figure prominently in the “Competitiveness and Resilience (CoRe) Partnership” launched at the U.S.-Japan leaders’ summit in April 2021. What then is at stake in developing a digital pillar to U.S.-Japan alliance? How can the allies devise a coordinated digital agenda to effectively address the China challenge? And what are potential pitfalls ahead?

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).