Watch the event discussion focused on how the Build Back Better Regional Challenge is ushering in a new era of national problem-solving, across geographies and in service of economic inclusion.

As federal policymakers seek to rebuild the nation in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, they are increasingly recognizing that bottom-up solutions are a critical path for spurring economic recovery, mitigating climate change, establishing supply chains in critical technologies, and addressing geographic inequities.

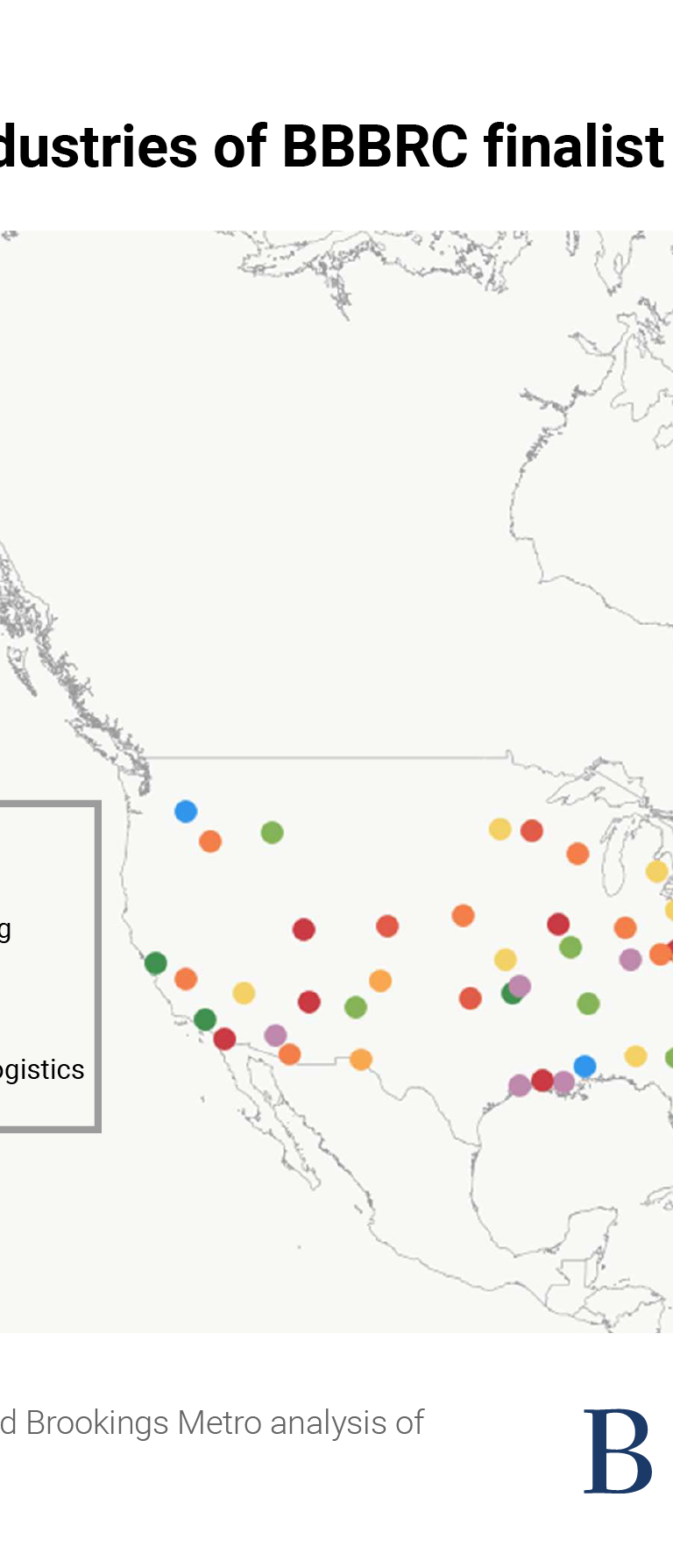

This is the central premise of place-based economic policies like the $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC)—a challenge grant administered by the Economic Development Administration (EDA) in the U.S. Department of Commerce. As the EDA’s signature American Rescue Plan (ARP) recovery program, the BBBRC provides five-year grants ranging from $25 million to $65 million across 21 regions1 competitively selected from a pool of 60 finalists2. With these resources, coalitions of businesses, governments, universities, and community-based organizations will implement comprehensive strategies to develop nationally critical industry clusters in ways that deliver economic opportunity to traditionally underserved people and communities.

In these ways, the BBBRC represents an important advancement in federal place-based economic policies—a school of policymaking that seeks to benefit people and economies by explicitly targeting geographies of concern. In that context, this report—the first in an applied research partnership between Brookings Metro and the EDA—provides early observations for policymakers, practitioners, and other stakeholders on the program’s design and selection phase. We find that:

Through large-scale, flexible funding, the BBBRC accelerated path-breaking regional economic development planning and coalition-building—a process that significantly strained the capacity of the 60 finalists. The EDA structured the BBBRC in two phases. In Phase 1, 529 regional coalitions submitted short proposals outlining a high-level vision, strategy, and coalition for their industry cluster. In Phase 2, 60 regional coalitions received $500,000 technical assistance grants to develop their proposals into full-fledged strategies—condensing into weeks what typically takes months or even years. This outpouring of interest illustrates the power of the “jump-ball” funding effect: how competitive federal programs can not only align regional leaders around a shared vision, but also inspire tremendous effort among those coalitions to develop comprehensive plans under ambitious deadlines. This process accelerated widespread impact, but significantly strained the capacity of regional applicants. To support regions through this planning sprint, the EDA created a multipronged technical assistance strategy involving multiple external partners.

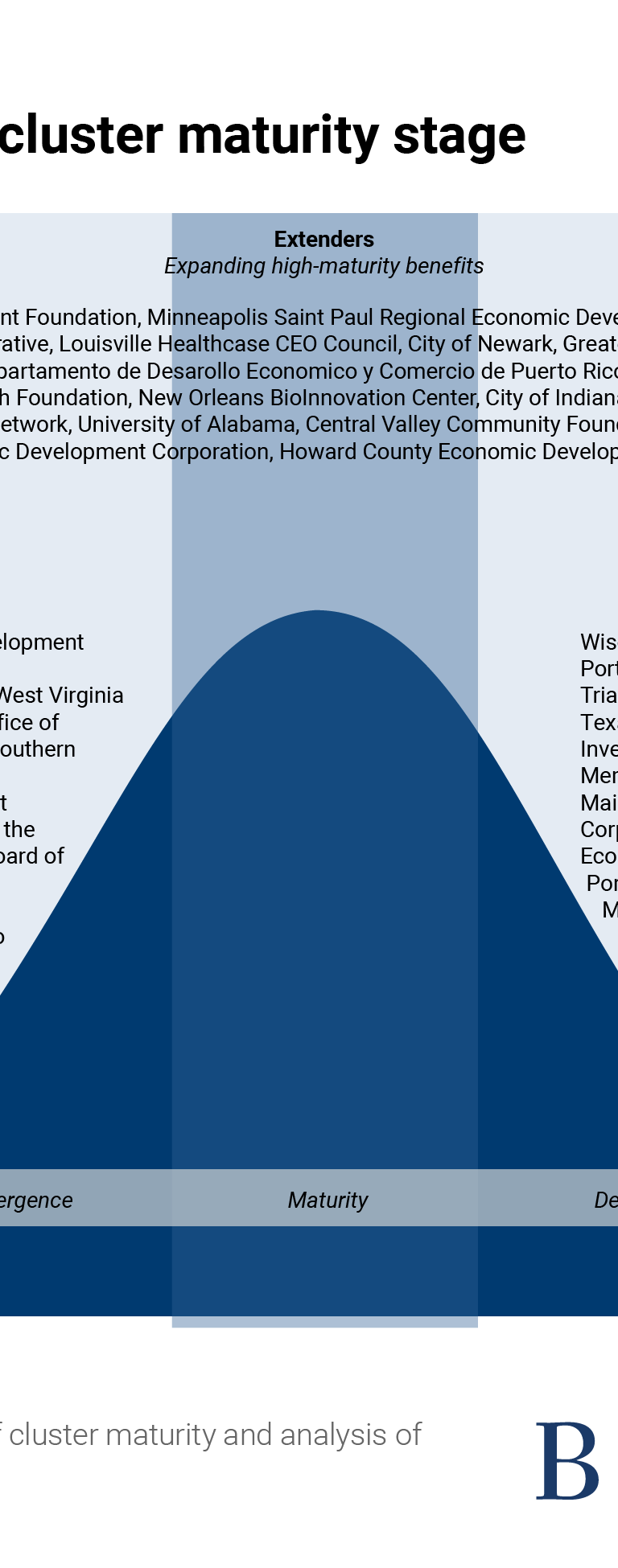

Across the 60 finalists, the BBBRC supported three different types of cluster-based economic development initiatives—maximizing the program’s relevance across urban, rural, and tribal communities. Given the program’s focus on cluster-based economic development, the EDA asked applicants to explain their chosen cluster’s opportunities, its constraints, and its potential impact. Understanding “cluster maturity”—where a region’s cluster resides in the maturity lifecycle—was foundational to framing the cluster’s opportunities and constraints. Across the 60 finalists, we identified a three-part cluster typology consisting of:

- Contenders: Twenty-two coalitions focused on emerging clusters, contending that they could use federal investment to accelerate low-maturity clusters (often in the energy space) into growing and established clusters.

- Extenders: Twenty-one coalitions focused on established clusters, often in advanced manufacturing, biotechnology, and information technology. Because these clusters are mature but not yet distressed, these coalitions’ objective was to extend the reach of the cluster’s assets in ways that enhance competitiveness and benefit more people and businesses within the region.

- Reinventors: The remaining 17 coalitions focused on declining clusters. These high-maturity clusters (often in agriculture and natural resources) have been under competitive threat for decades, and coalitions are now seeking federal resources to reinvigorate them.

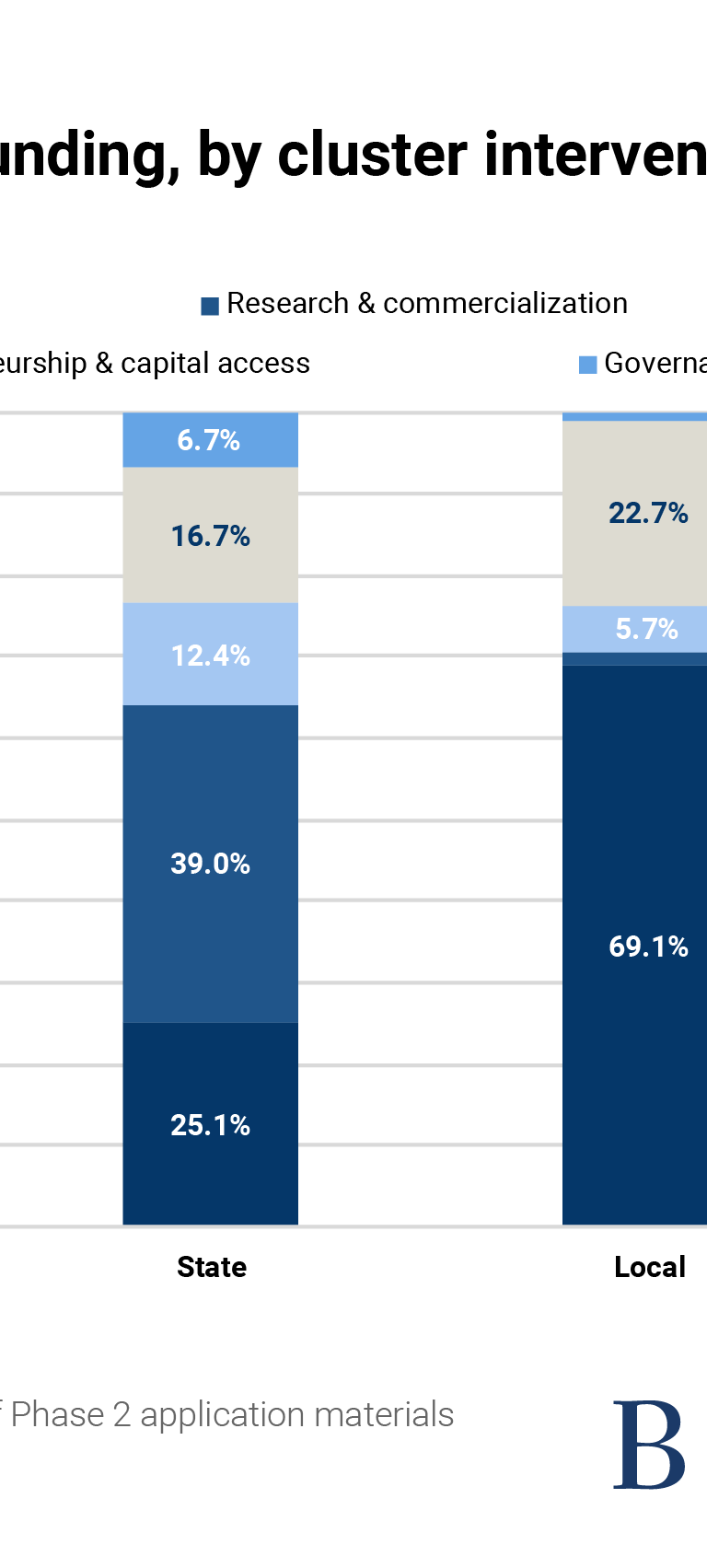

The BBBRC required applicants to create a coherent portfolio of proposed interventions, but left it to them to determine which specific projects would best advance their clusters. Creating one-size-fits-all federal programs ignores the significant variation across local economies. The BBBRC’s designers recognized that cluster-based economic development requires multiple investments in several critical elements of economic competitiveness: talent development, research and commercialization, infrastructure and placemaking, entrepreneurship, and governance. Yet the BBBRC allowed regional coalitions considerable flexibility when designing interventions, which is reflected in the considerable variation in project portfolios across contenders, extenders, and reinventors.

Nearly 30% of total requested funding came from non-federal sources, including local and state governments, industry partners, and philanthropy. The EDA encouraged matching resources from several sources: lead applicants, local governments, state governments, and other sources (e.g., industry, philanthropy, etc.). Across all 60 Phase 2 applications, federal resources accounted for approximately 71% of the total requested funding. Applicants themselves accounted for another 13% of funds, followed by state governments (6%), other sources (6%), and local governments (4%).

To learn more about the breakdown of BBBRC requested funding, read page 23 of the full report PDF »

The BBBRC yielded three proposed cluster governance models, reflecting the diversity of institutions that co-govern local communities. There was significant variation in how BBBRC coalitions organized themselves, divided up projects, and distributed funding. At one end of the spectrum, there were coalitions in which the lead organization was allocated more than half of the total budget request. Of the 22 coalitions deploying this centralized governance model, half were led by research universities. At the other end of the spectrum are facilitative governance models, in which the lead organization was allocated less than 25% of the coalition’s total budget request. More than half of these 27 coalitions were led by industry intermediaries (16). Finally, another 11 coalitions operated shared governance models, in which the lead organization manages between 25% and 50% of the project portfolio. Among the 21 awardees, a range of institution types served as the coalition lead, including universities, regional economic development groups, community-based organizations, local governments, state governments, and philanthropies.

BBBRC coalitions will measure their impact through a uniquely broad mix of economic development metrics. Over 90% of coalitions chose to track metrics related to markets and business networks, human capital and workforce, economic activity and employment, and engagement and governance in at least one component project within their portfolio. Less commonly, coalitions included production and business capacity metrics (82%), financing and investment metrics (67%), and innovation and commercialization metrics (53%).

The BBBRC’s top priority was equity, but finalists had mixed success embedding equity in strategies, governance, and metrics. The EDA encouraged applicants to consider how federal funds would benefit populations that have suffered from historical and systemic discrimination, disinvestment, and disenfranchisement. Many applications referenced intentional efforts to conduct community outreach and engage community-based organizations during planning and implementation phases. In a smaller share of applications, coalitions committed to specific equity-oriented administrative activities within their governance models, such as creating dedicated equity interventions or hiring diversity, equity, and inclusion consultants. But most coalitions struggled to develop comprehensive equity plans that integrated equity into a governance model, articulated each intervention’s intended outcomes for historically excluded communities, and developed concrete metrics to track outcomes for these communities over time.

To learn more about the BBBRC’s focus on equity, read page 29 of the full report PDF »

This report was prepared by Brookings Metro using federal funds under award ED22HDQ3070081 from the Economic Development Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Economic Development Administration or the U.S. Department of Commerce.

-

Footnotes

- BBBRC awardees include: Southeast Conference (Juneau, AK), Central Valley Community Foundation (Fresno, CA), Osceola County Board of County Commissioners (Kissimmee, FL), Georgia Tech Research Corporation (Atlanta, GA), Wichita State University (Wichita, KS), Greater New Orleans Development Foundation (New Orleans, LA), Detroit Regional Partnership Foundation (Detroit, MI), Greater St. Louis, Inc. (St. Louis, MO), Invest Nebraska Corporation (Lincoln, NE), City of Manchester (Manchester, NH), The Research Foundation for the State University of New York (Albany, NY), Empire State Development Corporation (Buffalo, NY), North Carolina Biotechnology Center (Durham, NC), Indian Nations Council of Governments (Tulsa, OK), Oklahoma City Economic Development Foundation (Oklahoma City, OK), Port of Portland (Portland, OR), Southwestern Pennsylvania New Economy Collaborative (Pittsburgh, PA), Four Bands Community Fund Inc. (Eagle Butte, SD), The University of Texas at El Paso (El Paso, TX), Virginia Biotechnology Research Partnership Authority (Richmond, VA), Coalfield Development Corporation (Huntington, WV).

- Additional BBBRC finalists include: University of Alabama (Tuscaloosa, AL), Spruce Root (Juneau, AK), Greater Phoenix Economic Council (Phoenix, AZ), City of Tucson (Tuscson, AZ), Hopi Utilities Corporation (Flagstaff, AZ), University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (Little Rock, AR), Pala Band of Mission Indians (Pala, CA), Alameda County Waste Management Authority (Oakland, CA), Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation (Las Angeles, CA), Innosphere Ventures (Fort Collins, CO), Southeastern Connecticut Enterprise Region (Groton, CT), County of Hawaii (Hilo, HI), mHUB (Chicago, IL), City of Indianapolis (Indianapolis, IN), Kentucky Education and Workforce Development Cabinet (Frankfort, KY), Louisville Healthcare CEO Council (Louisville, KY), New Orleans BioInnovation Center (New Orleans, LA), University of Maine System (Farmington, ME), Howard County Economic Development Authority (Columbia, MD), Northeastern University (Boston, MA), Minneapolis Saint Paul Regional Economic Development Partnership (St. Paul, MN), The University of Southern Mississippi (Hattiesburg, MS), Las Vegas Global Economic Alliance (Las Vegas, NV), City of Newark (Newark, NJ), Central New Mexico Community College (Albuquerque, NM), Albuquerque Hispano Chamber of Commerce Foundation (Albuquerque, NM), CenterState Corporation for Economic Opportunity (Syracuse, NY), Piedmont Triad Regional Council (Kernersville, NC), MAGNET: Manufacturing Advocacy & Growth Network (Cleveland, OH), Pennsylvania Wilds Center for Entrepreneurship Inc. (Coudersport, PA), Departamento de Desarollo Economico y Comercio de Puerto Rico (San Juan, PR), URI Research Foundation (Kingston, RI), University of Memphis (Memphis, TN), Lamar State College – Port Arthur (Port Arthur, TX), Utah Office of Energy Development (Salt Lake City, UT), Virginia Tech (Blacksburg, VA), Washington Maritime Blue (Seattle, WA), West Virginia Department of Economic Development (Charleston, WV), Wisconsin Paper Council (Madison, WI).