The Department of Education has proposed a new set of rules focused on the financial return to students when they take the leap from a high school diploma to a college degree. You can find the (long) proposal here. Inside Higher Ed has a good summary of the proposed changes.

IHE also reports a very worrisome comment from the American Council on Education of Universities:

“The American Council on Education found that about 33 percent of programs at historically Black colleges and universities not subject to the gainful-employment rule would fail the debt-to-earnings or earnings premium test…”

The new rules propose a number of changes, including limits on debt-to-earnings ratios for a college’s graduates and requirements for greater financial transparency. However, I want to focus on one change—the earnings premium test—a test that sounds sensible and that would be sensible if the world were more equal, but that could devastate many HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) for reasons that are both clearly unintended and easily understood.

The basic rationale behind the earnings premium test (EP) is simple: The median graduate of a program has to earn more than what the median high school graduate earns. (I focus on four-year colleges here, but many of the new regulations will apply more broadly. See this for more information about accountability for many shorter programs.) Under proposed “gainful employment” regulations, if a for-profit institution or non-degree program in any sector fails the EP test for several years, the college will no longer be able to recruit students receiving federal aid such as Pell grants or federal student loans. As a practical matter, that’s a death sentence for most colleges.

What’s new in the current proposal is to collect these earnings premium data for all programs and sectors with the aim of increasing transparency throughout the higher education system. Though these programs would not be automatically subject to the same financial aid sanctions based on those metrics, the proposed regulations give broad, though opaque, authority for the Department to consider those metrics in determining institutional aid eligibility. Schools that persistently fall below the debt-to-earnings ratio would also need to disclose that to prospective students before those students could access financial aid.

Perhaps it is reasonable to say that if a typical student at a college won’t earn something more after graduation than the student would have earned with just a high school diploma, then the college isn’t doing its job. If all potential college students had the same earnings prospects if they had stopped education with their high school diploma, then the rule would be making the right distinction. But some students are likely to have lower-than-average earnings with a high school diploma and also lower-than-average earnings with a college degree…even if their income gain from going to college is every bit as good as the average gain.

This is exactly the typical situation for many Black Americans. Comparing the after-college earnings of Black Americans to the high-school-diploma earnings from all Americans sets the bar in the wrong place, as it is an apples-and-oranges comparison. Black Americans with just a high school diploma earn significantly less than the average American with a high school diploma. Thus, the simple EP calculation ignores any earnings improvement in a Black college graduate up to the point of average earnings for high school diploma holders. Since HBCU enrollments are largely Black, they risk failing the EP test even if they do as well by their students as other schools that serve significantly fewer Black students.

We can approximate how using a uniform cutoff affects Black students by using data from the American Community survey. I calculated median earnings separately for all Americans and for Black Americans only, both with a high school diploma only who are either employed or seeking employment between the ages of 25 and 34 (that being the ages the Department of Education suggests). I then looked at earnings of college graduates aged 25 through 27—the Department of Education suggests looking at college students three years after graduation—and asked how many had earnings below the high school median earning cutoff. The results are shown in the table below, which compares recent college-graduate earnings to two different “cutoffs” shown in the table: one using the proposed standard of median high school graduate earnings for everyone, the other cutoff using median high school graduate earnings for Black Americans only. We can then compare the percentage of college grads below the proposed cutoff to the same percentage if the earnings test were based on Black earnings instead.

|

Percent of recent college graduates earning below high school median |

||

|

Using median HS-only earnings for all students (approximately $29,000) |

Using median HS-only earnings for Black students (approximately $24,000) |

|

|

All students |

27.0 |

21.3 |

|

Black students |

35.5 |

27.6 |

Source: Author’s calculations using the American Community Survey from 2017-2021 to estimate median wages for individuals with a high school diploma only in the labor force (either employed or seeking employment) between the ages of 25-34 and median wages for individuals with a college degree in the labor force aged 25-27. Both wages calculated for all workers and separately for Black workers

Compare the upper left and lower right entries in the table (all college completers’ earnings compared against all HS diploma holders’ earnings, and the same comparing among Black individuals only). They’re essentially the same at 27%. Black college graduates are just as likely as everyone to out-perform what their median earnings would have been with only a high school diploma. (And HBCUs specifically produce strong socioeconomic outcomes for their students.) The problem with the proposed regulation is that for HBCUs, it focuses on the lower left cell, which simply does not give an apples-to-apples comparison of the gain from going to college.

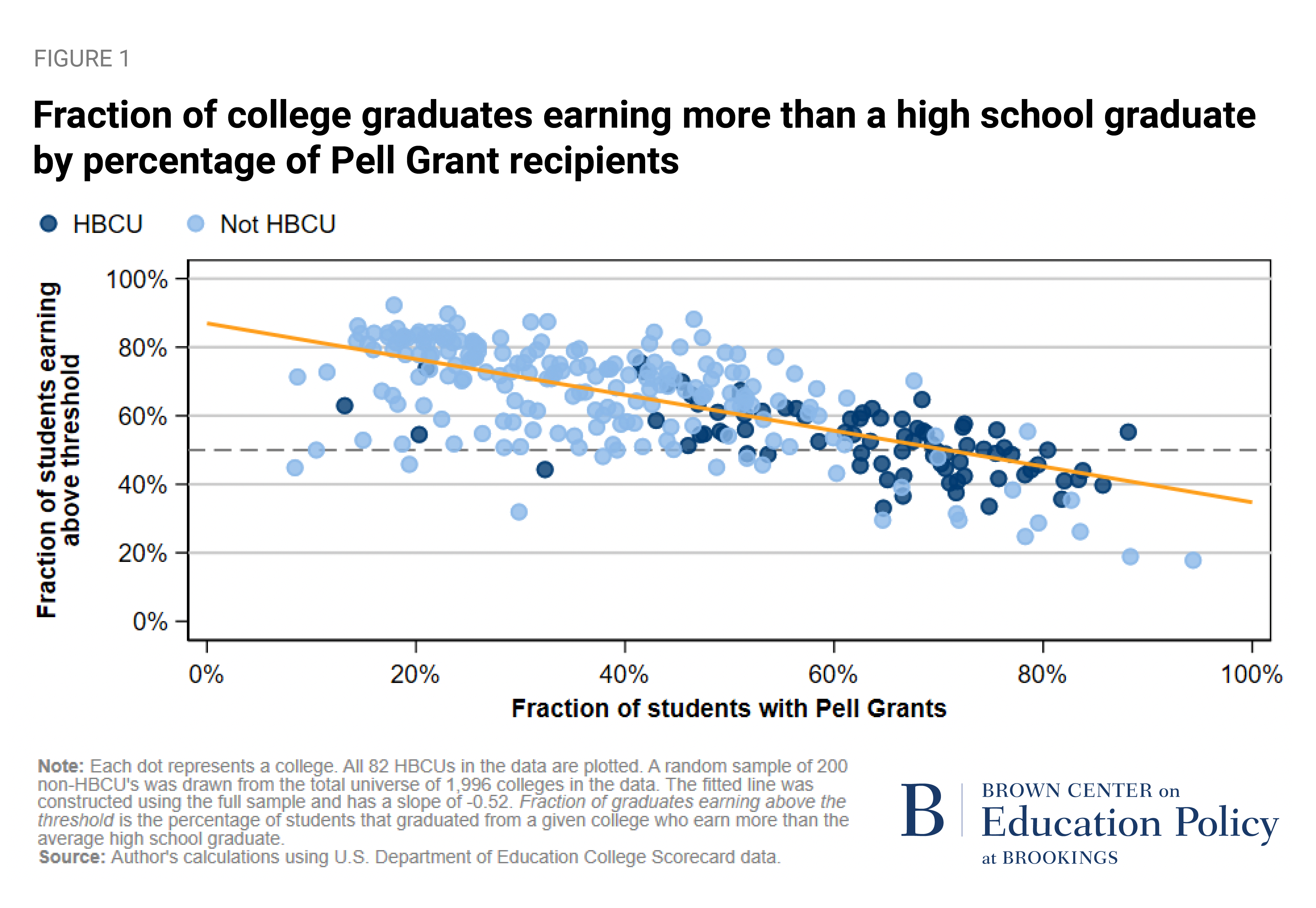

We can look more specifically at the gains from going to college by using approximations based on the College Scorecard data. The College Scorecard data provides two numbers for every bachelor’s-granting institution based on recipients of federal assistance: the fraction of undergraduates receiving Pell grants and the share of students earning more than a high school graduate eight years after entering college. The latter being above 50% roughly measures the proposed standard for keeping out of trouble on the earnings premium test. (You can see how your institution fares by going to https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/, entering the name of your school, then clicking “View School,” and then clicking “Typical Earnings.”)

The regression line in the figure above shows the relation between the fraction of undergraduates who end up above the estimated-for-everyone-earnings-premium and the fraction of students on Pell grants. The effect of a college or other institution concentrating on low-income students is huge. A student body where a quarter of the students are on Pell grants is predicted to graduate 74% of students above the threshold, while a student body where three-quarters are on Pell grants is predicted to graduate only 48% above the threshold. And (remembering that all this is an approximation) 48% is just enough to get all the latter schools under threat to be kicked off federal aid and effectively shut down.

In the figure, dark blue dots are for HBCUs and light blue dots are for a representative selection of bachelor’s-degree offering, non-HBCU institutions. (If all colleges were included, there would be so many dots that the picture would be a blue smear.) Points above the downward-sloping regression line mean that a college is doing better than one might expect given the number of Pell grant recipients it teaches, and, conversely, being below the line means that a college does less well.

The picture shows us several things. First, on average HBCUs have much higher Pell grant proportions than do non-HBCUs. (The median Pell grant fraction is 66% for HBCUs and 35% for non-HBCUs.) Second, many HBCUs score below the approximated high school earnings threshold. Third, high-Pell grant HBCUs don’t look much different from high-Pell grant non-HBCUs in terms of after-graduation income—it’s just that HBCUs are especially likely to serve low-income families. In other words, HBCUs faring less well on the earnings premium test is well explained by the fact that they serve so many low-income students.

Two takeaways:

- The proposed “one-threshold-fits-all” rule doesn’t make much sense for HBCUs, and probably doesn’t make sense for other colleges primarily serving lower income populations either. Even when a college provides solid financial value-added, it may not push the majority of its students above a high school-earnings level calculated for the entire population. HBCUs do a fine job financially raising their students’ earnings, but they serve a much lower-income audience than most other colleges.

- The proposed rule really does have the potential to effectively shutter a large number of HBCUs. The proposed regulations are ambiguous about exactly how the Department may use earnings premium data when evaluating most institutions’ financial aid availability, leaving colleges guessing how they might be impacted. Colleges should not face such uncertainty in their operations, wondering if or how a given administration will use these accountability data, nor should they be unfairly punished for serving higher-need student populations.

Paying attention to economic returns from going to college makes sense. One-size-fits-all rules don’t.

American Community Survey data is from IPUMS-USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Proposed earnings premium benchmarks threaten HBCUs

July 25, 2023