As Oroville, California, braces for more rain following a near disaster at the country’s tallest dam, officials are scrambling to make repairs and provide answers to more than 180,000 evacuees living downstream. Constructed in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains almost 50 years ago by the California Department of Water Resources, the Oroville Dam stands at a crucial point in the state’s extensive network of reservoirs, aqueducts, and distribution facilities that manage the water supply for millions of urban residents and farmers far into Southern California. Aging and in need of costly maintenance, the Oroville Dam embodies many of the concerns facing other dams around the country.

Given the enormity of the challenge and the national attention it has received, the events at the Oroville Dam have spurred calls for a more active federal role in rebuilding American infrastructure. However, rhetoric can only go so far in the face of the country’s long-standing challenge to plan and pay for these improvements, and Washington simply cannot tackle such a herculean task on its own.

Instead, the Oroville Dam crisis should serve as a reminder of just how much infrastructure oversight falls under state, local, and even private leadership. By looking at the regional variety in dam investment, ownership, and structural quality across the country, it becomes clear that the infrastructure challenges and solutions remain highly nuanced and require extensive coordination beyond the federal government.

Each year, the federal government is responsible for about $9.8 billion (35 percent) of public spending on infrastructure linked to water resource management, such as dams, levees, lakes, and rivers. By comparison, states and localities shell out nearly twice that amount ($18.3 billion or 65 percent), concentrating on operations and maintenance. When considering other types of water infrastructure, such as drinking water and wastewater facilities, the state and local role is even more significant, with up to 96 percent of public spending falling on their shoulders.

The fact that most of the nation’s dams are not federally owned or operated also points to the continued importance of regional action in this space. According to the most current data from the National Inventory of Dams, for instance, the federal government is the primary owner of only about 3.7 percent of the nation’s nearly 90,000 dams – although many of these tend to be quite large in physical scope. Meanwhile, state and local governments own 7.3 percent and 20 percent of all dams, respectively. The private sector, however, is the biggest owner by far (64.2 percent), illustrating how dam oversight and investment can vary markedly across the country.

Of course, the number of dams with higher risk potential differs substantially from state to state as well. From a high of 7,395 dams in Texas to a low of 83 dams in Delaware, the scale of needed regulatory involvement, ongoing maintenance, and infrastructure investment is hard to nail down consistently at a national scale, making it difficult to use the Oroville Dam as a typical example of what is happening elsewhere. For instance, 15,460 of the country’s 90,000 dams (17.1 percent) pose a potentially “high hazard” to the economy, environment, and human life if they were to fail. States like Hawaii, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania contain the highest share of dams in this category – over 44.5 percent—while states like Iowa, South Dakota, and Kansas contain less than 11.6 percent.

Beyond the potential for hazards, the current age and condition of dams is also crucial to consider at a regional scale. Most dams nationally are reaching the end of their useful life following the building boom of the early- to mid-20th century. In total, 62,700 of the country’s 90,000 dams (69.3 percent) were built before 1970, increasingly representing a physical and financial burden for many places. With up to 97 percent of their dams built more than a half century ago – or longer – many states in the Northeast are especially susceptible to these challenges, including Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New Jersey.

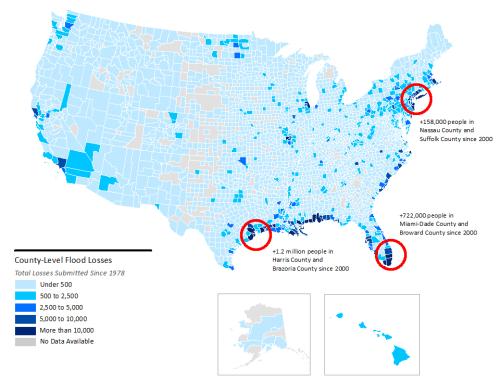

Just as the Oroville Dam showed warning signs a decade ago – including aging, insufficient spillways to handle extreme rain – states, localities, and their private-sector peers need to be more vigilant in their oversight and maintenance efforts nationally. Coming up with the money to actually carry out these activities remains perhaps the biggest hurdle of all, but several places along the Gulf Coast and elsewhere are establishing a new precedent for action by investing in more resilient infrastructure systems, including the exploration of new bonds and procurement strategies. Federal leaders, both in Congress and at an agency level, have also embraced initiatives to heighten investment in resilience, but the rising number of climate concerns demand additional attention in years to come. It will cost the country less over time if it can increase public and private sector investment now, rather than wait for the next dam failure.

While the Trump administration and Congress continue to grab most of the headlines of what should be done following the Oroville Dam crisis, state and local leaders need to be a big part of this conversation. Additional federal support would obviously help regions tackle these challenges head-on, much like their long list of other infrastructure projects, but a top-down solution is not going to be sufficient by itself. Continued regional leadership from the bottom-up is crucial to define the country’s most pressing infrastructure needs and build momentum for future action.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Oroville Dam, a reminder that infrastructure challenges go far beyond Washington

February 16, 2017