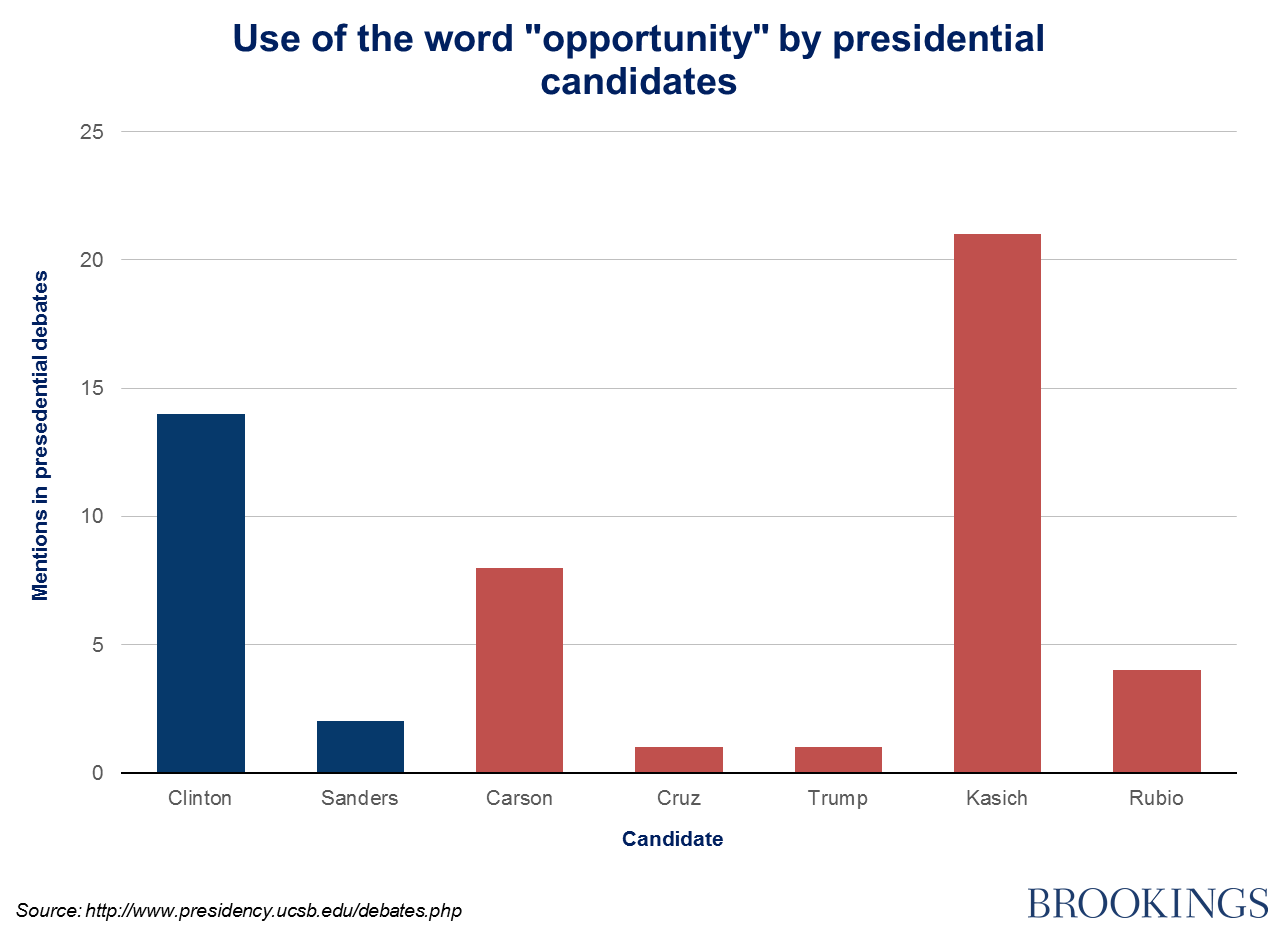

Hands up if you’re against opportunity. Yeah, thought not. That’s one reason politicians like the term, even in an ugly contest like the one for this year’s presidential nomination. It’s particularly appealing to the more centrist politicians: Hillary Clinton and John Kasich have used the word “opportunity” far more often than their rivals in prime time presidential debates:

Kasich has declared, “You know, the conservative movement is all about opportunity.” Secretary Clinton has said, “I’m running for president to…rebuild the ladders of opportunity that will give every American a chance to advance.”

What do they mean by “opportunity”?

But opportunity is a protean word, changing shape and meaning. More specificity is required for the ideal of opportunity to gain any policy purchase. A good start is to figure out what success would look like, and what data points would be needed to demonstrate it. That means adopting a series of opportunity indicators. As Alice Rivlin wrote in her seminal 1972 book Systematic Thinking for Social Action (recently reprinted by Brookings Press), “analysts who want to help improve social service delivery should give high priority to developing and refining measures of performance.” Rivlin also urged adopting a dashboard measures for complex social goals: “Multiple measures are necessary to reflect multiple objectives.” In the decades since Rivlin issued her cri de coeur, both data and analytical capacity of government at all levels have improved by leaps and bounds. But there is much further to go, especially in terms of defining and quantifying social mobility.

Opportunity data, please

Good indicators require good quality data. But notwithstanding recent scholarship from Raj Chetty and others, intergenerational mobility suffers from what Kenneth Prewitt, former director of the Census Bureau, describes as “a serious gap in the nation’s statistics.” There are good ideas on the table here, including the creation of an American Opportunity Survey by linking together various administrative datasets, including the Census, American Community Survey, Survey of Income and Program Participation, as well as data from the IRS and Social Security Administration.

On the political front, there is a promising push from House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) and Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA) for the creation of an independent Evidence-Based Policymaking Commission to “expand the use of data to evaluate the effectiveness of federal programs and tax expenditures.” This may not sound very exciting to most. But, as I argue in a new book chapter (“How Will we Know? The Case for Opportunity Indicators”), it is thrilling for policy. Organizations like Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy are trying to help state and local governments to build integrated data systems.

Institutionalize the opportunity commitment

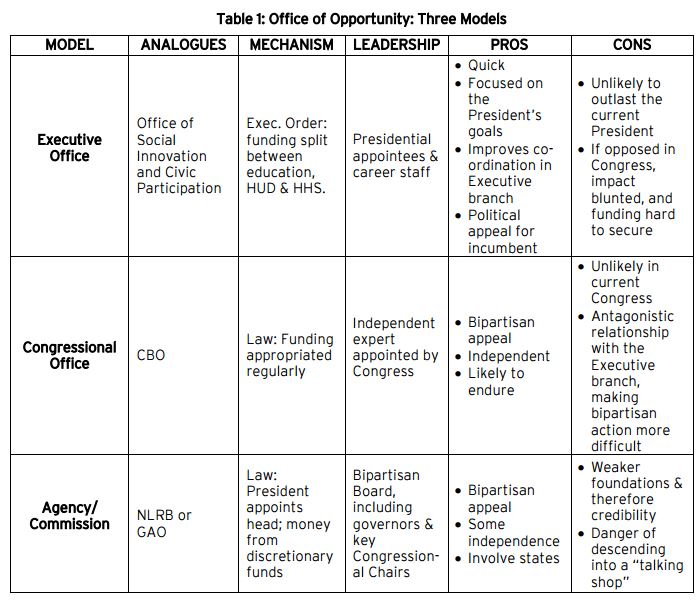

Of course, the issue is not just about collecting data, it’s also about sharing it effectively among key players. An important step would be to institutionalize the national commitment to opportunity in an Office of Opportunity. There a number of models for such an Office. It could be established as White House Office (as both Opportunity Nation’s Monique Rizer and Scott Winship from the Manhattan Institute have recently argued), as a Congressional body (or perhaps added to the work of the CBO), or as an agency. Each of these comes with pros and cons:

The rhetoric of opportunity is appealing. But progress requires attention to the mundane matters of data, indicators, institutions, and analysis.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Now, about that Office of Opportunity…

March 2, 2016