This viewpoint is part of Foresight Africa 2024.

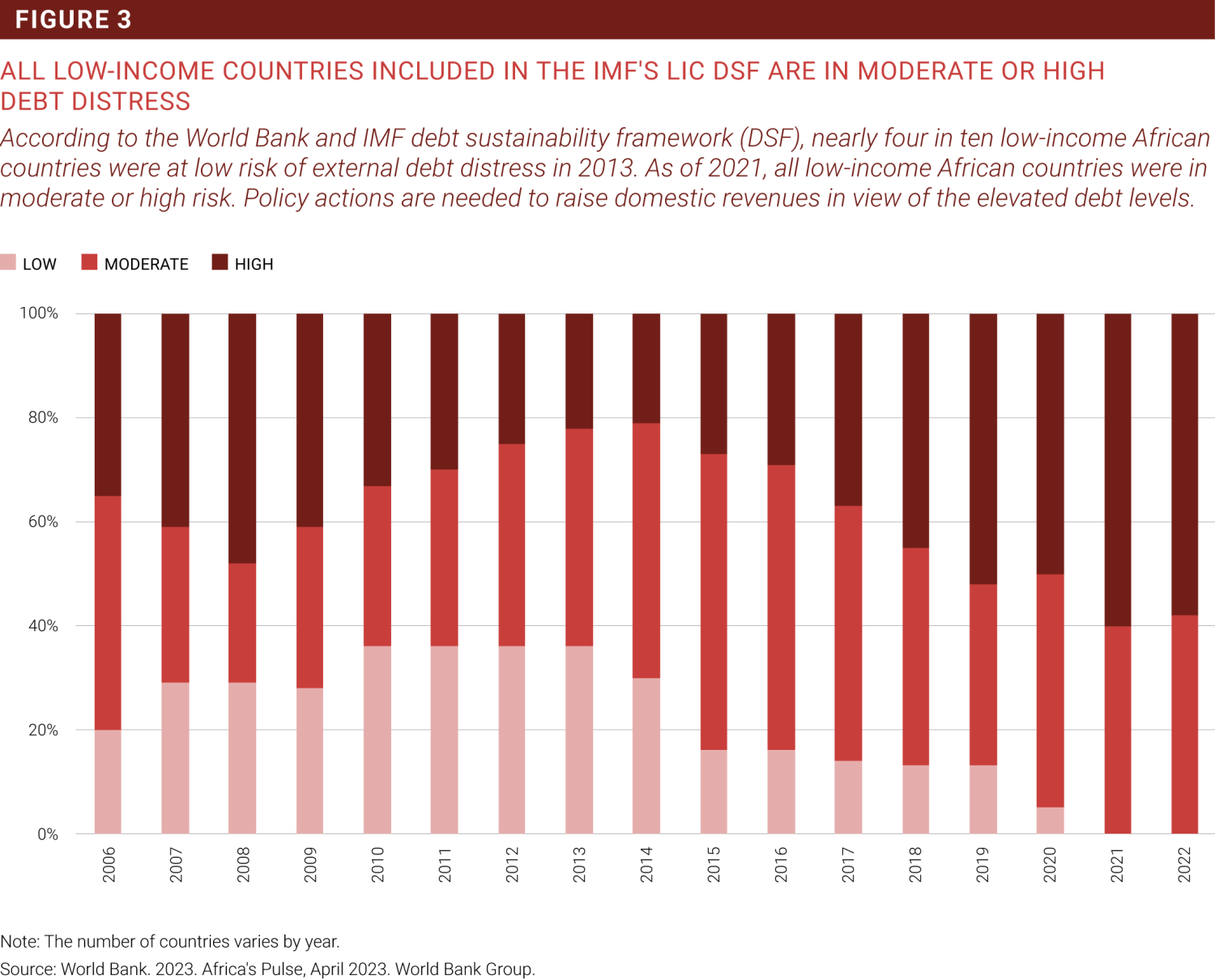

Public debt in sub-Saharan Africa has risen to levels not seen in decades, reaching almost 60% of GDP by the end of 2022. Repaying this debt has also become much costlier. The region’s ratio of interest payments to revenue, a key metric to assess debt servicing capacity and predict the risk of a fiscal crisis, has more than doubled since the early 2010s and is now close to four times the ratio in advanced economies, according to the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database. As of 2022, more than half of the low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa were assessed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to be at high risk or already in debt distress.

In a recent paper, we discuss in detail policies needed to reverse these worrisome trends and preserve the sustainability of public finances, while also achieving the region’s development goals. In our view, one of the fundamental weaknesses that plagues the conduct of fiscal policy in Africa is the absence of clear medium-term strategy and an excessive focus on short-term fiscal deficit goals without a clear vision of where the debt trajectory should go. This weakness, which we describe in the paper as a “lack of anchoring,” has resulted in frequent breaches of fiscal rules and ever-increasing public debt levels.

One of the fundamental weaknesses that plagues the conduct of fiscal policy in Africa is the absence of clear medium-term strategy and an excessive focus on short-term fiscal deficit goals without a clear vision of where the debt trajectory should go.

A more strategic approach to fiscal policy would be preferable by setting explicit debt targets that integrate key policy trade-offs between debt sustainability and development objectives. The paper suggests a novel methodology to estimate country-specific medium-term debt anchors, which ensures that debt service costs remain manageable. According to this methodology, the median debt anchor for sub-Saharan Africa is about 55% of GDP; slightly more than half of the countries were above their anchor at the end of 2022.

The analysis also shows that most countries in the region will need to reduce their fiscal deficits in the coming years. For a typical country, the amount of adjustment is estimated at about 2% to 3% of GDP, which seems feasible given historical experience. In the past, sub-Saharan African countries have been able to improve their primary balance by 1% of GDP a year over two to three years.

But not all countries face the same challenge. According to our estimates, about a quarter of the region’s economies still have some fiscal space and can use it to maintain and even increase vital investments in human and physical capital. In contrast, a few countries have very large adjustment needs; for them, it is unlikely that fiscal consolidation alone will be enough to ensure fiscal sustainability. It may need to be complemented by debt reprofiling or restructuring.

Regarding the composition of adjustment, sub-Saharan African countries tend to rely excessively on expenditure cuts to reduce their fiscal deficits. Although this may be warranted in some circumstances, revenue measures, like eliminating tax exemptions or digitalizing filing and payment systems, should play a greater role. While difficult to achieve, large and rapid increases in revenue have been observed in some countries like Rwanda, Senegal, and Uganda, which relied on a mix of revenue administration and tax policy measures.

Commentary

Navigating fiscal challenges in sub-Saharan Africa: Resilient strategies and credible anchors in turbulent waters

February 27, 2024