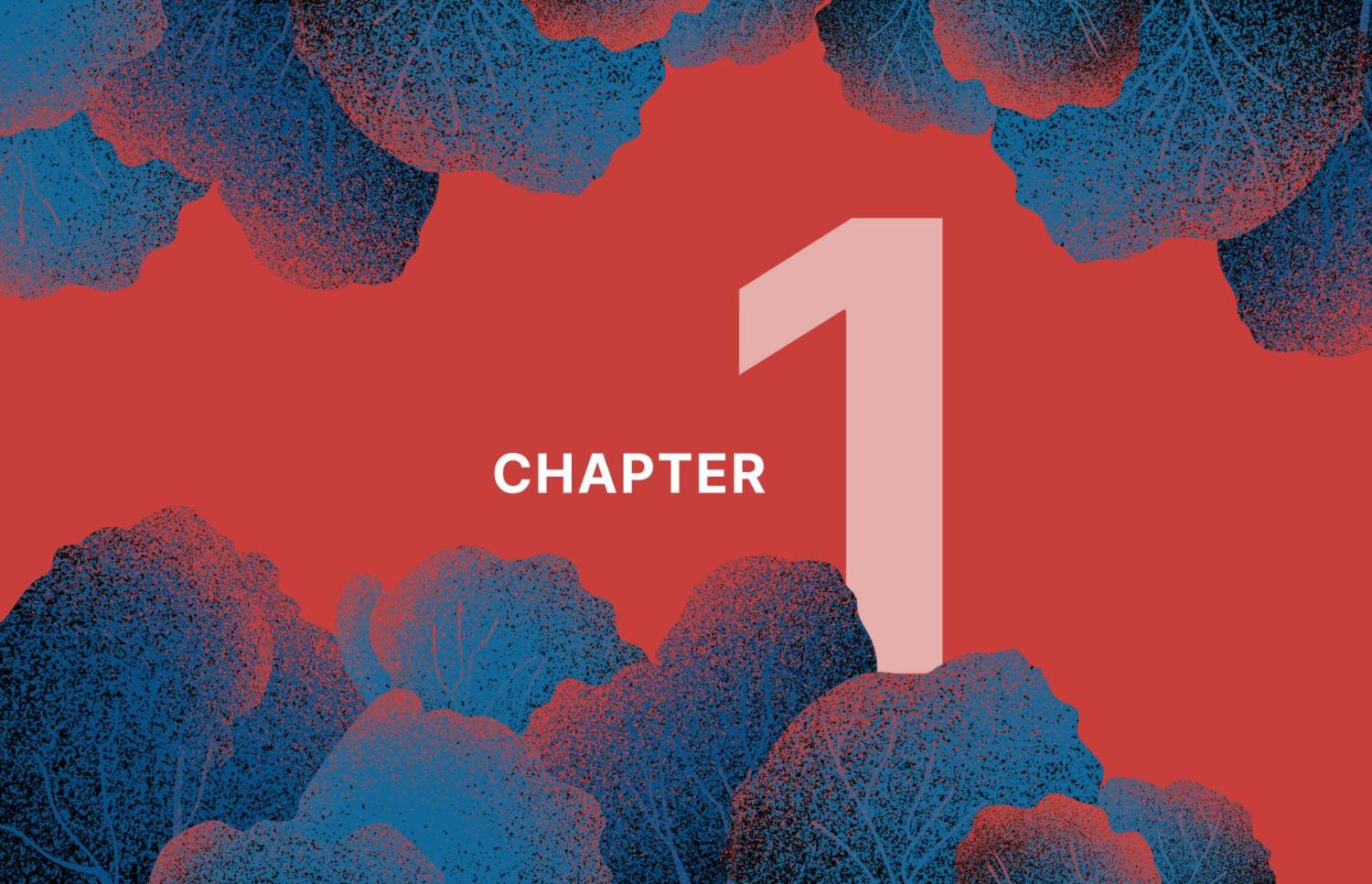

In Chapter 1 of Foresight Africa 2024, our authors share policy options to address economic challenges facing the continent.

Essay

Perspectives on African sustainable development finance

By Lemma Senbet, Dean’s Chaired Professor, University of Maryland, College Park

Over the years, African economies have undergone frequent turbulence—both economically and politically. Despite this tortured path, numerous countries have sustained growth over two decades with positive outcomes on livelihoods, including substantial poverty alleviation. Far from accidental, these outcomes are the result of genuine economic and financial sector reforms. The region has likewise witnessed an entrepreneurial spirit among the young and, home-grown innovations, such as M-Pesa, fueling growth of mobile banking around the globe.

Africa’s integration into global financial markets has a dark side, however. African countries have witnessed a rapid buildup of debt, obligations that the pandemic amplified. The Russian-Ukrainian war further exacerbated the debt situation with the attendant rising costs. Africa’s inflated debt levels and debt servicing costs would not have been such a big deal if all this borrowing had made a dent in the development financing gap. Recent estimates suggest it has not. According to U.N. data, the development financing required to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals runs close to USD $3.3-$4.5 trillion per year, with the lion’s share of the financing gap facing developing economies.1 For Africa, the infrastructure requirements, including support of its climate change adaptation and mitigation, is estimated to cost between USD $68 billion and $108 billion per year.2

Therefore, urgent action is needed to adapt global financial networks to foster a robust, sustainable flow of development finance into Africa. Responsibility for shaping financial networks can be broadly shared among international actors and Africa’s own domestic policies with home-grown solutions.

Responsibility for shaping financial networks can be broadly shared among international actors and Africa’s own domestic policies with home-grown solutions.

The role of the international community

In the short run, African economies can benefit from more efficient debt resolution and restructuring systems. At the global level, the G20 is already at the forefront of global coordination for the resolution of sovereign debt crises. It spearheaded the Common Framework for Debt Treatment in debt restructurings and resolution. While the Common Framework has faced many obstacles to becoming operational at scale, debt restructurings in Chad and Zambia offer hope for what is possible. Restructuring USD $6.3 billion of Zambia’s debt offers particular hope, as it resulted in a net present value reduction of outstanding debt.

While developed countries have the potential to be a considerable source of direct financing for development, the volume of financial pledges has greatly exceeded financial commitments in this regard. A glaring example is climate funding. During COP15 in 2009, there was a bold agreement to provide climate funding of USD $100 billion annually by 2020. By 2020, an estimated USD $80 billion of the USD $100 billion had been met annually. It is encouraging, though, that the delivery gap in climate funding pledges received prominent attention at the Paris Summit with President Macron confidently announcing that the pledge gap in the delivery of USD $100 billion (per annum) would be bridged by the end of 2023.

The development financing gap remains large and cannot be bridged by traditional sources of finance alone; it will require unlocking private capital at scale.

Overall, the development financing gap remains large and cannot be bridged by traditional sources of finance alone; it will require unlocking private capital at scale. Currently, private capital is not flowing at the speed and scale commensurate with the huge development financing gap. Among the barriers is the dearth of bankable deal flows in Africa. As a result, unlocking private capital cannot be done without the enabler of the public sector. The role of the public sector is crucial in providing de-risking vehicles to incentivize the private sector. In view of global economic uncertainty and shocks, de-risking vehicles can incentivize the private sector to take on large-scale, risky projects.

Thus, an enabling environment is needed in Africa for innovative green financing through the development of a pipeline of bankable and investable projects. Regional initiatives, including AfCFTA, working in tandem with global institutions (e.g., the G20), can serve as facilitators of collective action continentally to secure development of bankable projects and private capital flows to these projects. In particular, the G20, with the AU as its new member, can use its considerable convening power to bring a consortium of investment fund providers to the table. Finally, this is an opportune time to accelerate financial sector development that is fit for purpose to unlock private capital at scale.

The role of African internal policies: The way forward

When accessing global initiatives, African countries should take proactive measures and home-grown solutions to bridge the financing gap and build capacity for financial resilience. Here are some measures for priority attention in 2024.

- Accelerate domestic resource mobilization: Accelerating domestic resource mobilization (DRM) through speedy reforms of tax systems is urgent. At 16.5% of GDP, sub-Saharan Africa has a low tax revenue to GDP ratio vis a vis peer low-income countries outside the region.3 DRM can be greatly enhanced through improved audits and compliance, mitigation of leakages, and expanding the tax base.

- Promote green revolution: Africa should be part of a climate solution and lead its own green revolution. Climate action includes exploiting its abundant endowment of green minerals and potential for renewable energy, minimizing dependence on carbon-heavy industrialization, and leapfrogging into a new global economy characterized by resilience and inclusivity. This should be supported by an enabling environment for home-grown climate finance solutions and start-ups.

- Promote financial innovation and inclusion: Although African financial systems have recently grown both in quantity and depth, finance has not been inclusive in the region. This underscores the fact that financial system development is necessary but not sufficient for financial inclusion. Financial inclusion empowers the agents of inclusivity of development—youth, women, small farmers, SMEs—as they are among the most financially excluded in society. Africa is innovating in this regard. We have witnessed home-grown innovations which have received global attention, with Kenya at the center of this remarkable movement. Although the mobile money revolution spearheaded in Kenya is well known, less attention is given to an exciting banking sector innovation lead by Equity Bank. The Bank is a pioneering commercial bank that innovated a banking service strategy targeting low-income customers and traditionally underserved territories in Kenya. In our comprehensive study of Equity Bank we show strong evidence that an innovative banking business model focusing on the provision of financial services to population segments that are typically neglected by traditional banks can generate sustainable profits with social inclusion.4

- Unlock financial entrepreneurship and fintech: African countries have huge unbanked and underserved populations—an opportunity for the rise of home-grown financial entrepreneurs. Financial entrepreneurship can be unlocked through fintech start-ups enabled by the digital revolution. The advent of fintechs in Africa is a relatively new and remarkable development. Fintech startups in Africa are mobilizing mass market access to a menu of financial services—savings, credit, insurance, and other digital financial services. In 2022, African fintech startups secured USD $1.45 billion in funding, a 39.3% increase from 2021.5 It is also noteworthy that the fintech movement is venturing into the intersection of climate and finance with startups providing services in sustainable banking, climate insurance, impact investing, and ESG reporting. Strengthening fintech requires developing an enabling policy environment involving financial regulators and inclusive digitization.

- Integrate and consolidate the disparate capital markets: Except for South Africa, financial systems in Africa are still thin and malfunctional, as evidenced by the stock exchanges around the continent. These exchanges are largely characterized by low capitalization and low trading activity, relative to peer low-income countries outside Africa. It is crucial that these markets be consolidated through regional cooperation and initiatives involving harmonization of trading laws and accounting standards and promoting convertibility of currencies such as the Abidjan-based Bourse régionale des valeurs mobiliéres and the proposed Africa Exchanges Linkage Project (AELP). A potential game-changer for the financial integration movement in the continent, the AELP was launched in November 2022 by the African Securities Exchanges Association in partnership with the African Development Bank and other stakeholders to facilitate cross-border trading and investment within African capital markets. Along with capital market integration initiatives, the region is witnessing the rise of Pan-African banks, many of which are domiciled in South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Morocco, and Togo.

- Introduce digital financial regulation that is fit for purpose: African financial regulatory systems must catch up with the rapid pace of innovation and dynamism in financial systems. At the outset, it should be recognized that optimal regulation is an enabler, and not a stifler. The provision of inclusive financial services can be impeded by ill-designed regulatory systems. In particular, excessively tight financial regulation of entry and licensing requirements of mobile network operators can discourage them from using their networks to provide inclusive access to payments services by mobile phone subscribers. Financial regulatory policies should also resist the temptation of protecting vested interests against new entrants that provide innovative technology driven services.

- Develop talented financial manpower: Finance and financial innovation have become increasingly complex and dynamic. As African financial systems develop and integrate into the global financial economy, there should be a commensurate development of talented financial power with capacity to manage and control risk. The financial capacity development strategy should include talent to regulate. At a basic level, African financial regulators need to develop a deeper understanding of how banks and other financial institutions take and manage risk. There is a potential for partnership here. African financial regulatory institutions and financial institutions can partner with local and international knowledge institutions to produce financial manpower and regulatory force that matches sophisticated and complex financial systems characterized by digitization and financial innovation.

Viewpoints

More from Foresight Africa 2024

In Chapter 2, our authors tackle the existential climate change crisis.

In Chapter 3, our authors focus on policies to support Africa’s entrepreneurs and small businesses.

In Chapter 4, our authors examine trends in regional economic integration and trade.

In Chapter 5, our authors consider policy options to unlock the potential of the digital economy.

In Chapter 6, our authors explore the ways Africa’s women and girls are increasing opportunity for all.

In Chapter 7, our authors delve into ways African leaders can regain the trust of their citizens.

-

Footnotes

- UN Sustainable Development Group. 2023. “Financing and Funding: The Way Forward.” https://unsdg.un.org/2030-agenda/financing

- AFDB. 2022. “Africa Investment Forum: African investors asked to mobilize more for infrastructure in Africa.” https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/africa-investment-forum-african-investors-asked-mobilize-more-infrastructure-africa-56051

- T20 Indonesia. 2022. “Resolving debt crises in developing countries: How can the G20 contribute to operationalizing the common framework?” Task Force 7. International Finance and Economic Recovery. https://www.t20indonesia.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/TF7_Resolving-Debt-Crisis-in-Developing-Countries.pdf

- Allen, F., et. al. 2020. “Improving Access to Banking: Evidence from Kenya.” Review of Finance, Volume 25, Issue 2, March 2021.

- Disrupt Africa. 2022. “The African Tech Startups Funding Report.” https://disrupt-africa.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/The-African-Tech-Startups-Funding-Report-2022.pdf

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).