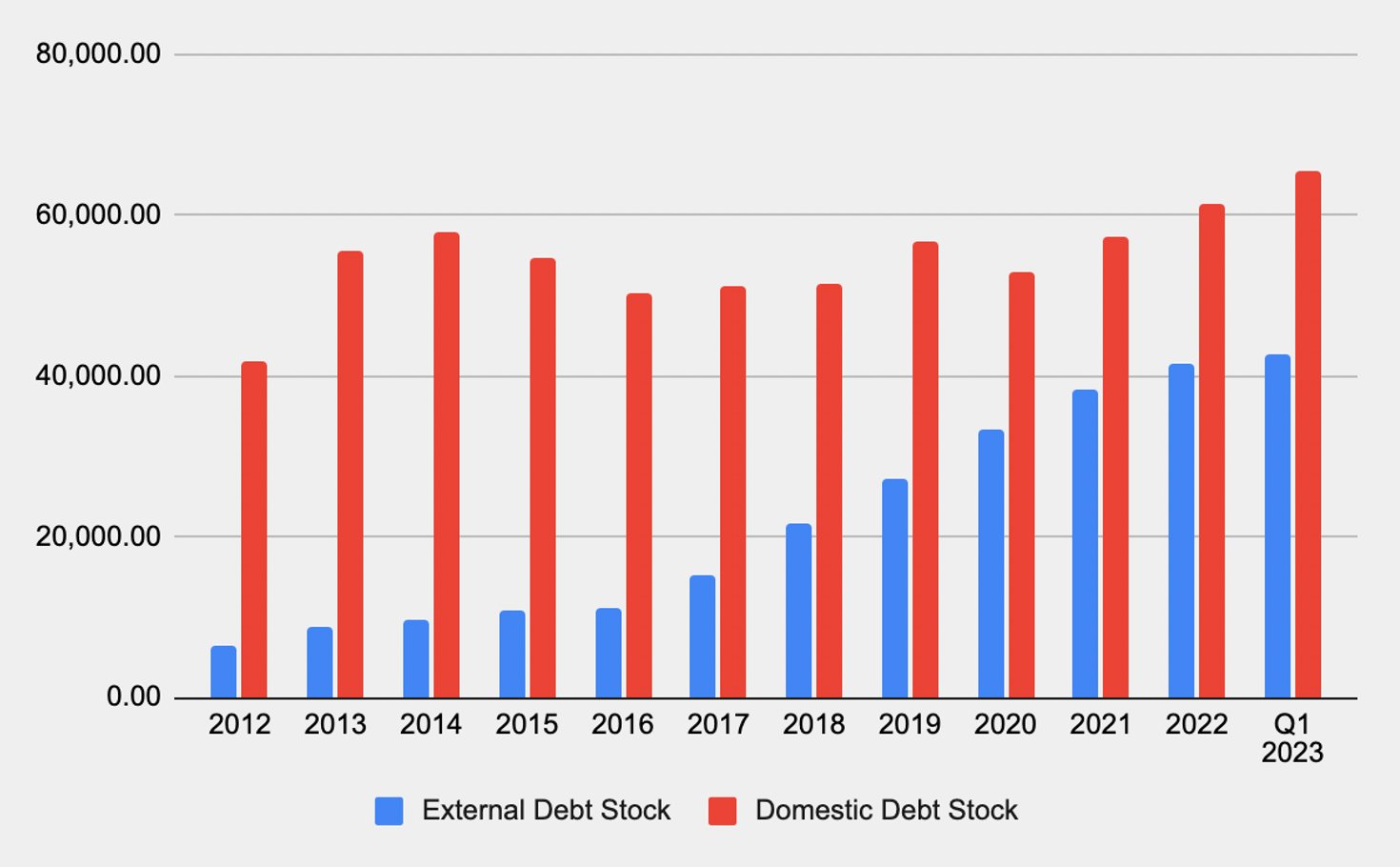

Despite the essential role debt plays in enabling structural transformation and development, the rate at which Nigeria’s debt is rising has constrained the country’s ability to generate sufficient growth, cope with crises, and invest for development. In 2023, Nigeria’s debt reached $108.3 billion. This represents an increase of 123% since 2012, a rate roughly six times the country’s growth rate of GDP. Nigeria’s increased debt is as a result of an interplay of factors including the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war. Most of the new debt has been externally obtained leading to an increase in the risk of the burden of that debt becoming unsustainable. This is because global financial pressures have weakened local currencies and increased interest rates, thus increasing the cost of servicing that debt in real terms. Nigeria’s external debt as a share of total debt has increased from 14% to 40% between 2012 and 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Nigeria’s external and domestic debt stock (Millions of US dollars); 2012 – Q1 2023

Source: Debt Management Office, Nigeria

There has also been a change in the creditor landscape: Most of the new debt is owed to multilateral and private creditors as opposed to bilateral creditors such as the Paris Club at the start of the new millennium. Whereas multilateral creditors accounted for 13% of total debt in 2005, presently, they account for 48% of total debt. Similarly, private creditor debt as a share of total debt has increased from 10% in 2005 to 38% in 2020. Meanwhile, bilateral debt as a share of total debt has declined significantly from 77% in 2005 to 14% in 2020. This has important implications as private creditors typically offer loans at relatively higher interest rates, with shorter maturity and grace periods. Moreover, coordination among creditors becomes more difficult as there is no formal coordination mechanism to bring together all creditors.

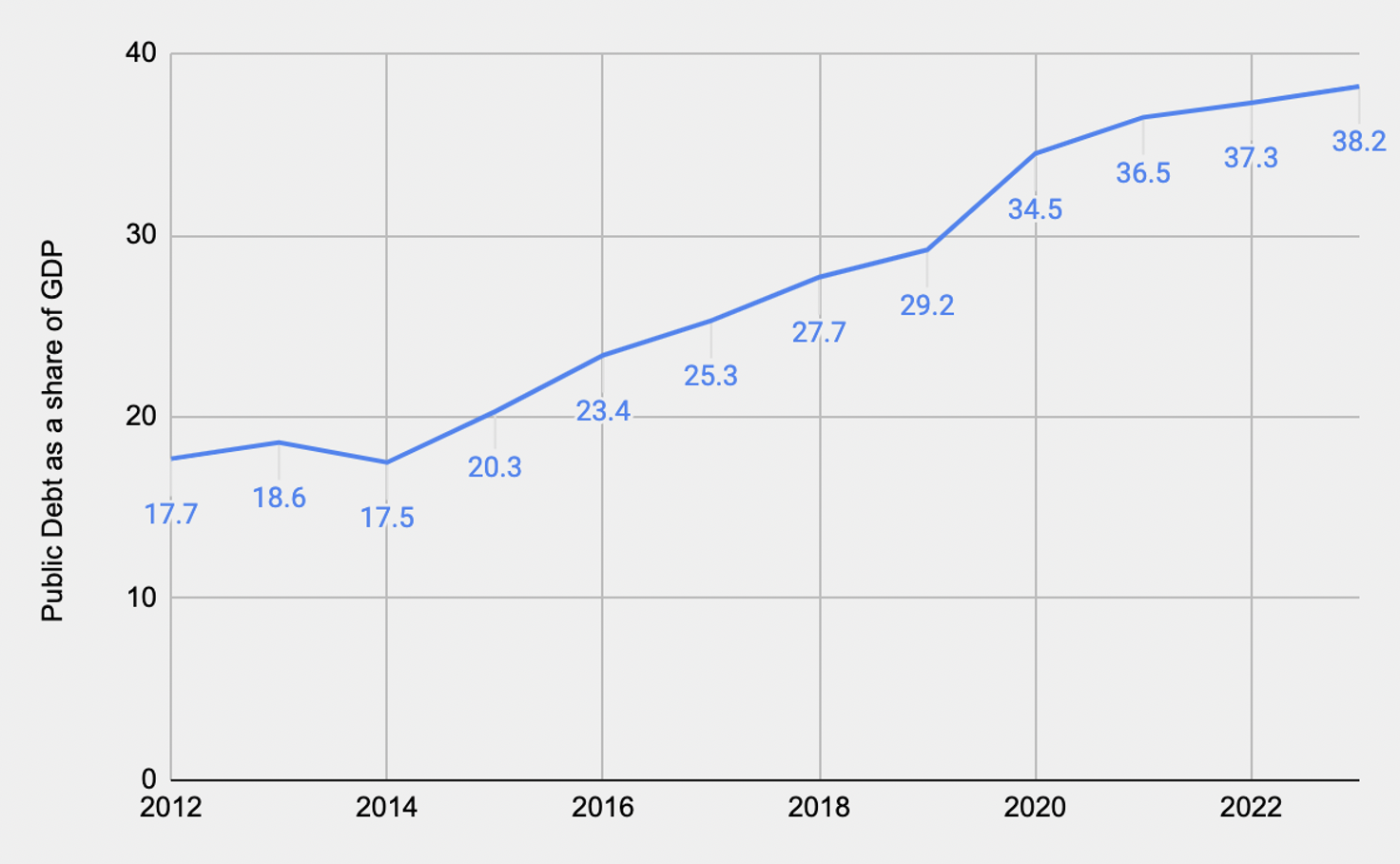

The high borrowing cost and rising debt is hindering Nigeria’s ability to finance its development agenda. Increasing amounts of public revenue are allocated for debt servicing purposes. In 2022, an estimated 96% of the federal government’s revenue was allocated toward interest payments. Understandably, debt servicing dwarfs investments in key sectors. In the 2023 national budget, the budget share for debt servicing is 29% whereas the budget shares for education, health, and infrastructure are 8%, 5%, and 6%, respectively. With interest payments gulping down public revenue, it has become a matter of urgency for policymakers, researchers, and development practitioners to put forward solutions capable of stemming the crisis.

Figure 2. Nigeria’s public debt as a share of GDP (%); 2012 – 2023

Source: IMF Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa, April 2023

At the start of 2022, researchers at the Center for the Study of the Economies of Africa (CSEA), together with partner institutions, began a three-fold research project aimed at offering fundamental fiscal policy options for growing out of debt in Nigeria. Here, we share high-level findings from the three studies (two still forthcoming) from CSEA, which include “Debt for Climate and Development Swaps in Nigeria,” “Determining the Optimal Carbon Pricing Policy for Nigeria,” and “Effects of Gender Inequality during Global Health Emergencies: Evidence from Nigeria.”

Two of these studies are linked to raising climate finance. Climate change is gaining renewed attention as changes in climatic conditions have begun to manifest in diverse ways including increasing temperatures, rising sea levels and the attendant flooding, as well as extreme weather conditions that indicate Nigeria’s vulnerability to climate change. Estimates show that climate change could result in a 6 to 30% loss of national GDP by 2050, estimated to be between $100 billion and $460 billion. According to the ND-GAIN (Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative) index, with a score of 38.5, Nigeria is ranked 154 out of 185 countries indicating its vulnerability to climate change. Meanwhile, Nigeria’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) estimates a financing requirement of $177 billion from 2021 to 2030 in order to meet the conditional target of cutting current emissions by 50% before 2030.

Debt for climate and development swaps in Nigeria

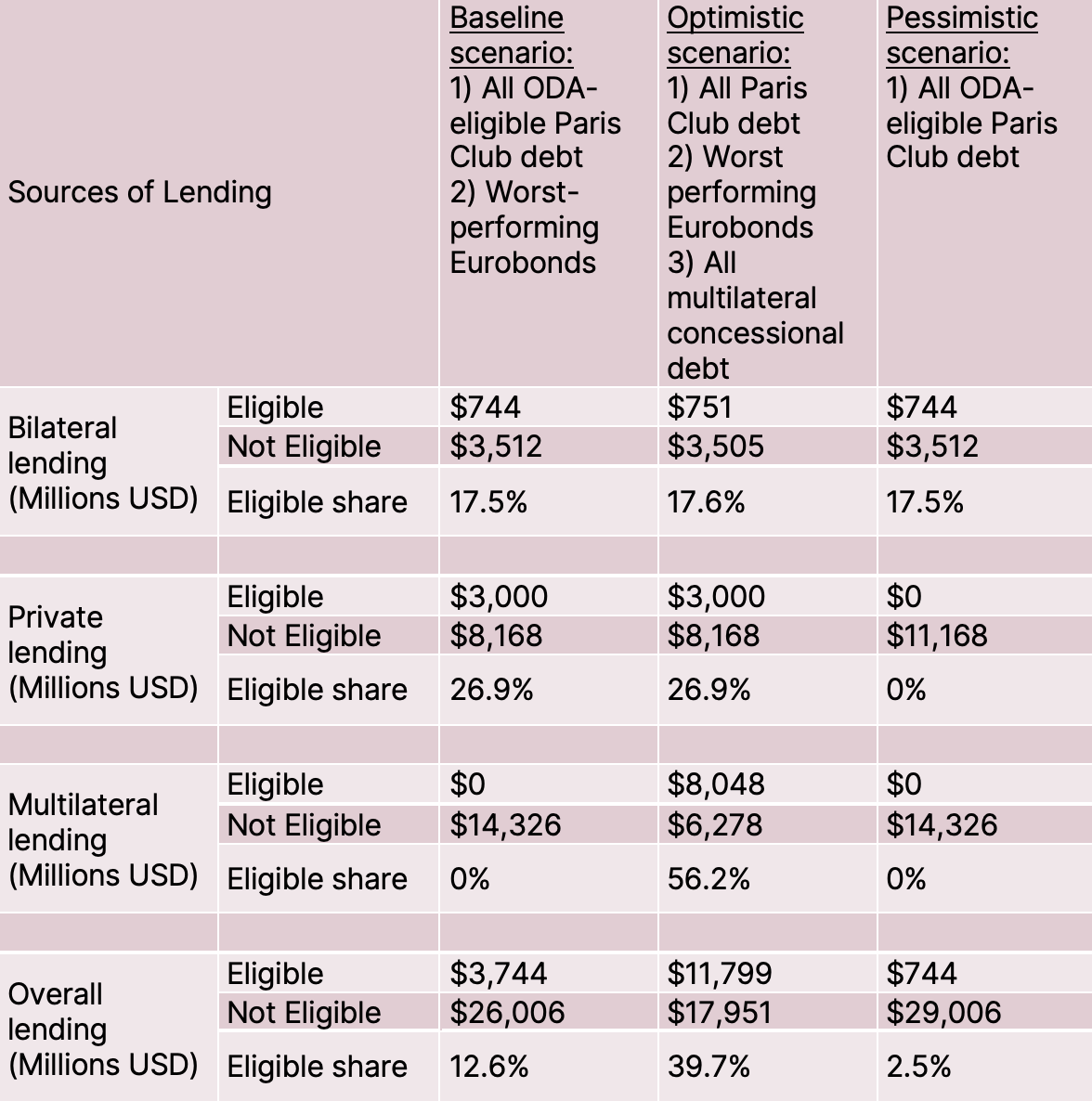

The rapid accumulation of debt together with the high vulnerability to climate risks and climate finance gaps positions Nigeria to benefit from financing innovations such as debt swap. Accordingly, debt for climate and development swaps—that is, exchanging debt service payments with an obligation to channel funds toward climate and nature as well as development outcomes—could create a win-win situation for both the debt and climate crises. However, based on historical precedence and/or an economic rationale, not all categories of debt can easily be swapped. The categories most likely to be swapped are (i) bilateral debt and in particular, ODA-eligible Paris Club debt (ii) Eurobonds trading well below their original price, and (iii) multilateral debt. Therefore, the paper shows the viability of debt-for-development swaps using a scenario analysis.

Under the baseline scenario covering all ODA-eligible Paris Club debt and worst-performing Eurobonds, up to $3.7 billion can be swapped (Table 1). Meanwhile, the optimistic scenario covering all Paris Club debt, worst-performing Eurobonds, and all multilateral concessional debt could lead to up to $11.8 billion being swapped. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the resources available for use generated by the debt swap depend on the debt-servicing schedules of the cancelled debt. The debt-servicing savings by year for Nigeria, assuming that the baseline scenario is realized, would free up an average of nearly $300 million per year. This sum can be used to finance climate-smart policies and projects particularly in the areas of infrastructure and power.

Table 1. Outstanding debt eligible for debt swaps

Source: Bloomberg, International Debt Statistics, Paris Club

Determining the optimal carbon pricing policy for Nigeria

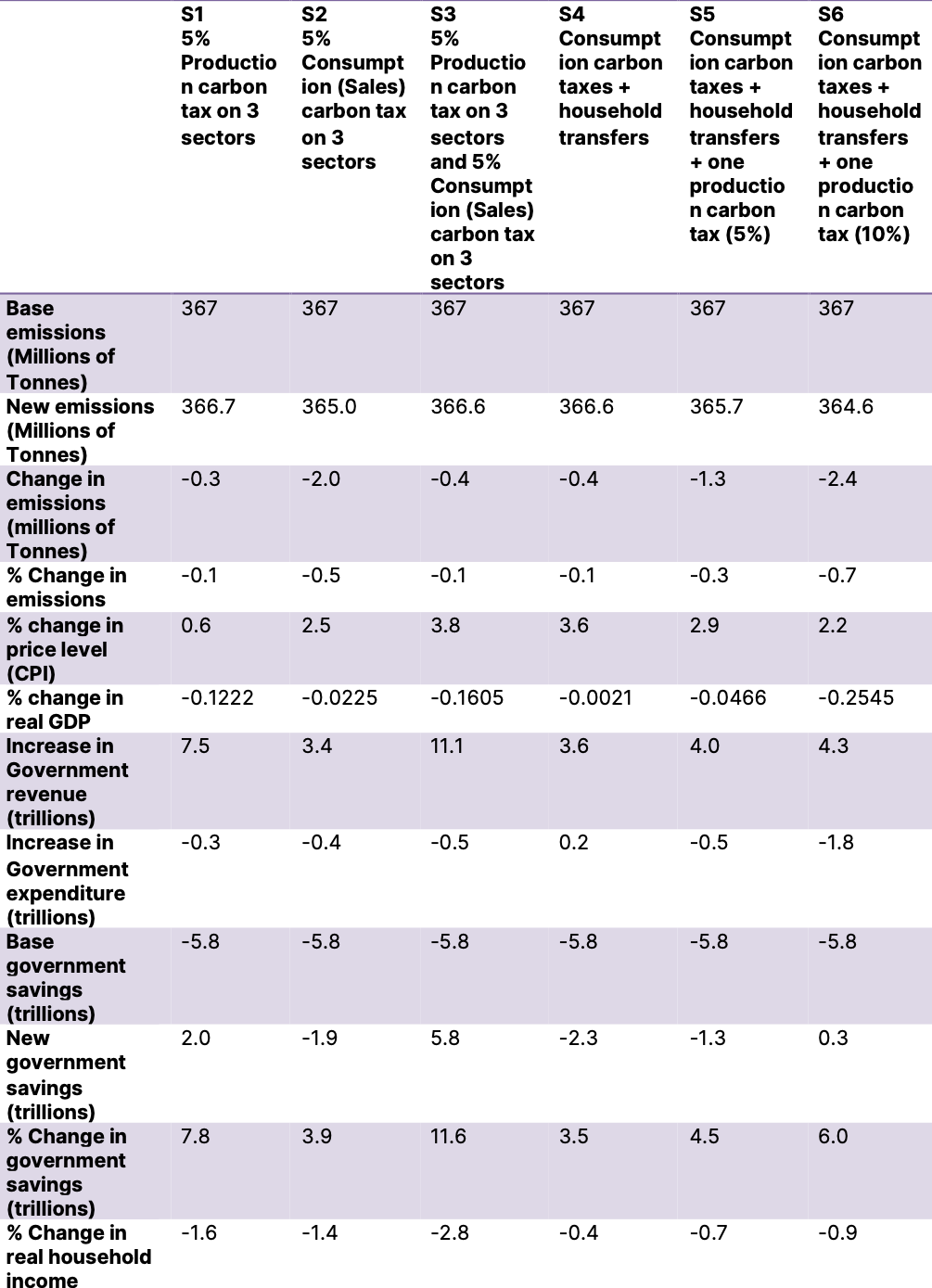

Carbon pricing remains one of the most effective policy instruments to facilitate low carbon transition and raise revenue for general fiscal purposes and, in particular, for climate-smart investment. Despite its potential, Nigeria has no explicit carbon tax policy for greenhouse gas reduction. Therefore, to facilitate carbon tax policy for Nigeria, the study (forthcoming) determined the optimal carbon pricing policy for Nigeria by identifying the scope of taxation, that is, the fossil fuel types, sectors, and activities to be covered; determining the regulation point, production or consumption; and ascertaining the optimal tax rate that will result in specific emissions abatement level and generate substantial revenue.

Specifically, the study simulates the imposition of carbon taxes in three forms: (i) production taxes on oil and mining, manufacturing, and services (with the exception of agriculture and firewood); (ii) sales taxes on consumption of diesel, kerosene, and manufacturing (with the exception of gasoline and firewood); and (iii) the removal of fuel subsidies, which function as an inverted carbon tax. It is noteworthy that a well-formulated carbon pricing policy often has multiple objectives as it impacts not only emissions and revenue but also poverty levels, inflation, and economic output. The study presents six scenarios that impose either a production tax, consumption tax, or both, and in some cases, include household transfers (see Table 2). The removal of fuel subsidy is implicit in all six scenarios. Based on the effects on the multiple objectives, a phased carbon tax is optimal, beginning with consumption carbon taxes in the short term and introducing production taxes later on. In Scenario 6 where a phased carbon tax and household transfers were implemented, carbon emissions reduced by up to 2.4 million tons and revenue increased by 4.3 trillion naira ($57.6 billion).

The study also ascertains the magnitude of taxes that may be necessary to achieve a reduction in emissions substantial enough to allow Nigeria to be on track to achieve a 20% unconditional reduction by 2030 as targeted. Using the structure of carbon tax rates in Scenario 6 as a base, the simulation indicated that up to a 30% production tax on the oil sector and consumption tax between 7.5-15% would be needed to achieve the short-term target of reducing emissions from 367 million to 351 million tons by 2021 (which would put the country on track to achieving the 2030 target). These rates are relatively high and indicate the need for a gradual approach to implementing the carbon tax.

Table 2. Overall effects of carbon tax on the economy

Effects of gender inequality during global health emergencies: Evidence from Nigeria

Global challenges including pandemics, climate change, and debt crises are having a disproportionate impact on women relative to their male counterparts. Due to the roles women play in the economy, society, and politics, they remain more susceptible to negative impacts when disruptions to business as usual occur. The primary objective of the study (forthcoming) is to examine the micro and macro effects of gender inequality on economic development during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as to identify the extent to which women and women’s issues are underrepresented in macroeconomic policy development, decisionmaking, and implementation in Nigeria.

The COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected women across several dimensions including unemployment, education, health and nutrition, child care, and gender-based violence. For instance, women are overrepresented in sectors that are more susceptible to the pandemic’s impact such as accommodation and food services (89%), trade (65%), human health and social services (61%), and education (50%), leading to high unemployment among women.

Furthermore, the study shows that gender inequality contributes to a shortfall of 36.25% of Nigeria’s real GDP per capita. Based on this output loss, the model then simulates what the growth rate would have been if gender parity was in place in Nigeria. Under gender parity, Nigeria’s growth in 2020 would have declined by 1.14% rather than 1.8%. By projection, it would also grow by 3.6% in 2023 and 3.4% in 2024 rather than around 2.5%. Further simulations show that the revenue projection of 7.4% of GDP for 2020 could be much higher at 8.6% of GDP under the assumption of gender parity. The negative micro and macro effects of the pandemic are due to the fact that Nigeria’s policies, institutions, and law-making apparatus fall short of addressing gender equity concerns, including the implementation of gender policies and laws.

In conclusion, growing out of debt will entail restructuring debt to improve fiscal space for spending on key sectors. Policymakers should engage in debt for climate swaps with creditors to make available up to $11.8 billion for climate spending. Furthermore, the implementation of a phased carbon tax (consumption carbon taxes in the short term and production taxes later on) can potentially reduce carbon emissions by up to 2.4 million tonnes and increase revenue by 4.3 trillion naira ($57.6 billion), some of which can be used to provide temporary, targeted, and timely assistance to households and firms to alleviate the impact of the tax on household income. On gender parity and economic growth, improvement in implementation and enforcement of laws in support of women can improve government revenue by up to 9% of GDP.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Fiscal policy options for growing out of debt: Evidence from Nigeria

September 28, 2023