A thoughtful, provocative report on intergenerational mobility just landed on my desk. It adopts an innovative approach to measurement, is honest about the costs as well as benefits of relative mobility, and avoids the narrow economic determinism of so many studies. It’s from Mexico.

The report, authored by Roberto Vélez Grajales, Raymundo M. Campos and Juan Enrique Huerta Wong, and published by a new organization, the CEEY (Standing Committee on Social Mobility), is worth a read for anybody interested in social mobility, Mexico, or both.

The main conclusion of the research is that Mexico has low rates of relative intergenerational mobility, and in particular very high persistence at the top of distribution. More than half of Mexicans raised in a family in the top quintile of the distribution of a measure of socioeconomic status (combining financial assets and occupational status) will remain there as adults. Another one in four will fall just one quintile.

Four Mexican Mobility Lessons

Four features of the report stand out:

- The challenges posed by downward relative mobility are addressed head-on, which is unusual. (We’ve tried, a bit). As the authors write, “In general, no one opposes the objective of promoting absolute social mobility, namely seeking to improve everyone’s wellbeing. However, attempting to promote relative mobility may raise doubts. This difficulty, to a large extent, arises from the possibility that people will experience relative downward social mobility.”

- A multi-dimensional approach is adopted. This is appropriate, since Mexico is also a pioneer in the development of a multi-dimensional poverty measure. But it is also valuable in itself, since mobility is about much more than money. Four dimensions are examined: education, occupation, wealth, and perception.

- The philosophical underpinnings of a focus on social mobility are treated seriously. Not enough reports open with descriptions of the competing ideas of justice put forward by John Rawls, Amartya Sen, and John Roemer.

- The subjective side of mobility and aspiration is examined, along with the ‘hard’ measures of money and schooling. As the report states, it is important to consider “psycho-cultural factors in mobility processes”, because “socioeconomic wellbeing is fundamentally subjective. What people believe it means to live well and how high aspirations form, resonates in the idea of wellbeing, and even that of happiness.”

Perceptions of Mobility, By Quintile

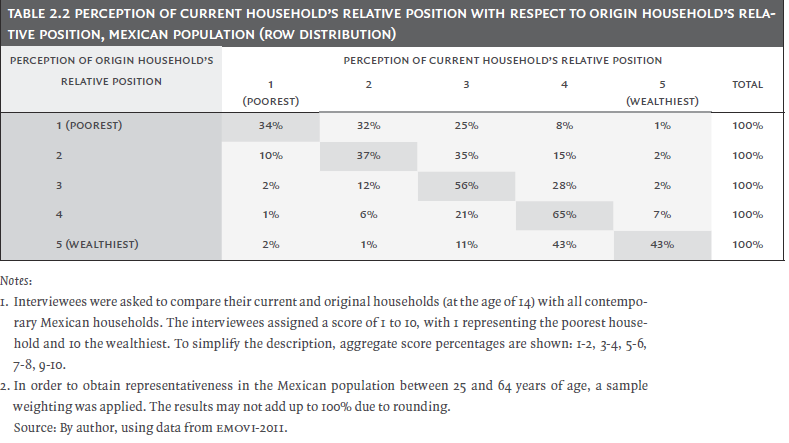

The report even constructs a quintile transition matrix of how much mobility people think there is, alongside the ones attempting to measure the real trends. It turns out that Mexicans are even gloomier about mobility than the fairly gloomy facts:

Source: Roberto Vélez Grajales, Raymundo M. Campos and Juan Enrique Huerta Wong, 2014

As the report concludes, “Mexicans sense a higher persistence in position of origin…which suggests a tendency to think that things “stay the same” when, in reality, the flux is greater than perceived.” Of course, aspiration is an important factor in explaining mobility, too. Perceptions can change reality, as well as the other way round. Time for a Mexican Dream?

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Mexican Thinking on Social Mobility

October 7, 2014