Content from the Brookings-Tsinghua Public Policy Center is now archived. Since October 1, 2020, Brookings has maintained a limited partnership with Tsinghua University School of Public Policy and Management that is intended to facilitate jointly organized dialogues, meetings, and/or events.

Earlier this decade, Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz proclaimed that two significant forces would shape global prosperity in the 21st century: U.S. technological innovation and urbanization in China.

The latter’s relevance of course stems from China’s immense scale and how the political, environmental, and economic conditions in its cities ripple across the world in profound ways, influencing everything from global climate prospects to socioeconomic conditions in industrial communities in the United States.

This makes understanding urban China extremely important, if challenging. Limited data and complex political dynamics complicate the task, but our latest Global Metro Monitor offers one perspective on recent economic trends in China’s large cities. Three findings stand out:

One-third of the world’s 300 largest metropolitan economies are now in China.

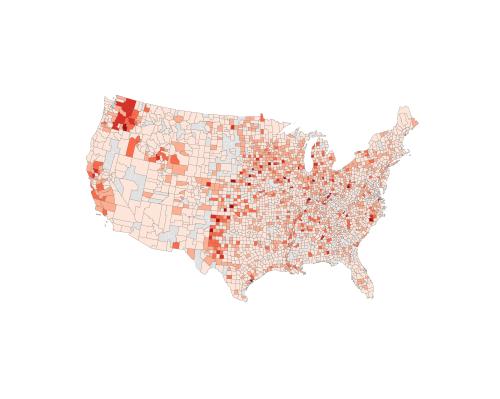

Brookings Metro’s Global Metro Monitor draws on GDP and employment data from Oxford Economics to track the economic performance of the world’s 300 largest metropolitan economies, as measured by GDP. When we released the last iteration of the report in 2014, China accounted for fewer than 50 metro areas within the top 300. In this version, measured using 2016 data, this number increased to 103, more than North America and Western Europe combined.

A combination of rapid economic growth and a re-accounting of China’s GDP based on improved measures of the purchasing power of Chinese consumers drove this rapid increase in large metro economies. Even as economic growth in China slowed by recent standards, Chinese metro areas significantly outpaced the rest of the world with 7 percent annual GDP per capita growth between 2014 and 2016 (Figure 1).

Five different urban Chinas drive the nation’s economic growth.

While China’s cities are at the frontier of global growth, many of them are still little known to the world. And in a country this large, there is no one “city type.” Urban China is as complex and varied as the United States. To examine these variations, we classified the 103 Chinese cities in our report into five unique categories based on their size, industrial composition, and growth patterns (Figure 2):

- Two Chinese Giants, Beijing and Shanghai, are economically dominant, together housing 26 million workers and generating over $1.6 trillion in real output.

- Anchor Cities are 14 other metro areas that generated at least $200 billion in real output. They make up a quarter of the nation’s GDP in 2016, including nine provincial-level municipalities or provincial capitals (Tianjin, Chongqing, Zhengzhou, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Guangzhou, Wuhan, Changsha, Chengdu) and five coastal cities that are home to some of the world’s busiest container ports (Qingdao, Suzhou, Wuxi, Ningbo, Shenzhen).

- China’s own Rust Belt contains six metro areas (Harbin, Daqing, Changchun, Jilin, Shenyang, Dalian) in Northeast China, struggling to counter the decline of the nation’s coal and steel industry.

We differentiate China’s remaining 81 metro areas—most of them mid-sized (average employment of 1.6 million and average GDP of $106.9 billion)—based on their industrial structure:

- In 24 metro areas, services account for a higher share of the economy than industry. We categorize these as Service Cities.

- In 57 metro areas, industry accounts for a higher share of the economy than services. We categorize these as Industry Cities.

The “five urban Chinas” have differing economic performance, over both the short and long term.

How do these five types of metro areas perform economically? To measure economic performance, we utilize two indicators—total employment and GDP per capita—and take into account both the rate of growth and magnitude of change in those indicators between 2014 and 2016, the latest data available. We then rank all 103 Chinese metro areas on this combined index.

The two Giants and 14 Anchor Cities perform generally well among the 103 Chinese metro areas, with a mean index rank of 26 and 18, respectively (Figure 3). Rust Belt metro areas occupy the bottom of the rankings, with an average rank of 94. The performance of mid-sized metro areas is more mixed, although Service Cities (48) perform slightly better than Industry Cities (58).

These short-term growth dynamics represent the latest update of what have been significant long-term differences in economic growth across the five types of Chinese metro areas. Since 2000, these five types of metros have exhibited distinctive employment and GDP per capita growth patterns. While Beijing and Shanghai still get most of the headlines, they no longer serve as the main engines of national economic growth (Figure 4). Domestic migration has been shifting from Beijing and Shanghai to smaller cities for a decade. This trend is likely to persist as China implements population caps in Beijing and Shanghai, leaving little room for additional labor inflows. The gap in average living standards (measured by GDP per capita) between the two Giants and other Chinese metro areas is also shrinking. Since 2000, GDP per capita in China’s 101 metro areas outside of Beijing and Shanghai rose twice as fast as in the two Giants.

Anchor Cities remain significant drivers of growth. These metro areas are usually the regional hubs for transportation, with well-connected domestic high-speed rail and international airports or seaports. They also house many of the country’s tech unicorns, including Alibaba (Hangzhou), Tencent (Shenzhen), and Huawei (Shenzhen). As China’s Anchor Cities transition toward higher-value industries, skilled labor shortages are forcing them to aggressively compete for talented workers, including from Beijing and Shanghai.

Not all Chinese metro areas are thriving, however. China’s own Rust Belt has experienced a decade of weak employment growth and a more recent GDP per capita growth slowdown. Located in the three northeastern provinces, these Rust Belt cities were once home to the nation’s largest manufacturers of cars and aircrafts in the planning era, but started to lose ground as inefficient state-owned enterprises failed to stay profitable in an increasingly competitive market. The region shares the common challenges of industrial decline and population loss that its U.S. counterparts are facing.

Finally, growth trends in Service and Industry Cities have tracked similarly since 2000. Both sets of cities have doubled their labor force and quintupled GDP per capita in the 16-year span. This similarity is not surprising as many Service Cities were, in fact, industrial hubs of the past. Meanwhile, China has incentivized coastal manufacturers to move inland instead of abroad, allowing less developed cities across central China to follow the same industrial development roadmap as their coastal counterparts.

The rapid growth in coastal metro areas that traditionally depended on industry has resulted in rising wages and land prices. Cities like Fuzhou, Xiamen, Wenzhou—the three Service Cities that ranked among the top 10 on the Economic Performance Index—have benefited largely from booming financial services and e-commerce, despite their heavy reliance on manufacturing less than a decade ago. On the other hand, Zhanjiang—the only Service City ranked in the bottom 10—has been unable to find a new growth industry to counteract the decline of its industrial base.

A closer look at the Pearl River Delta—a region of nine cities and 60 million people—exemplifies this dynamic (Figure 5). Once the “factory of the world,” the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region is in the midst of a dramatic economic transition. In some parts of the region, cities are thriving. Guangzhou leads the nation in cross-border e-commerce, and Shenzhen has emerged as the Silicon Valley of China. At the same time, in other corners of the region’s cities—such as Dongguan, Foshan, Jiangmen, Zhongshan, and Zhuhai—are experiencing slow growth or decline as they struggle to evolve their economies away from competing on low costs towards new product innovation. The losses in these cities have been gains for cheaper nearby cities such as Huizhou and Zhaoqing, which are still rooted in industry. Like China itself, the PRD is not a monolith, and whether its economy will remain rooted in the past or embrace a high-tech rebirth remains to be seen.

China’s unprecedented urbanization ensures that its cities will collectively shape and define national trends related to infrastructure, technology, and economic growth. And because those cities loom large on the world’s economic stage, their continued evolution will help dictate key global economic, social, and environmental outcomes.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Meet the five urban Chinas

Wednesday, June 20, 2018