The opioid epidemic, ongoing since the 1990s and increasingly deadly during the COVID-19 pandemic, is linked to another long-standing and hard-fought public health crisis: HIV. People who inject drugs (PWID) experience elevated rates of HIV acquisition and transmission, a tendency that has been exacerbated by the opioid epidemic. Because this group is a potent vector through which HIV remains active in our society, changes in policies that affect PWID can have broader public health ramifications.

In a new study published in the International Journal of Drug Policy, researchers found that without careful and deliberate mitigation efforts in place, criminal justice reforms that result in large, rapid decreases in incarceration rates can lead to an increased risk of HIV spread through communities.

To identify this unintended hazard, authors of the paper had to overcome substantial research challenges: collecting data on PWID is difficult, and there are multiple overlapping sources of influence through which policy might affect HIV transmission. The Brookings Institution’s Center on Social Dynamics and Policy worked with colleagues across several institutions to create a sophisticated computational simulation tool that can provide insight into potential policy effects. Recently published research includes a description of this tool along with findings from our application of it to multiple types of relevant policies.

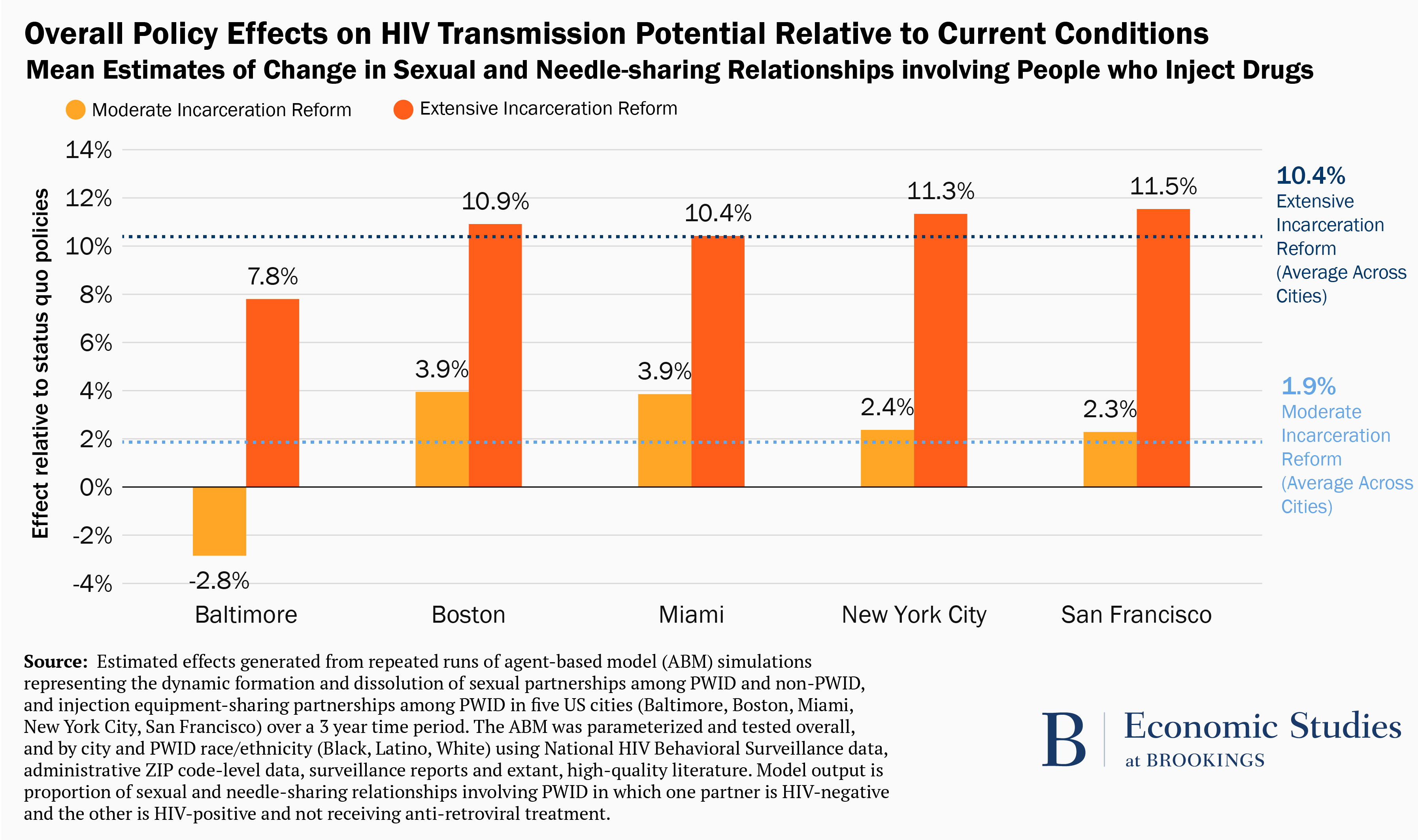

In each of the five metropolitan areas considered, simulations indicate that criminal justice reform policies that result in extensive reductions in incarceration rates increase relationships involving PWID that have the potential for HIV transmission (figure 1). On average, there is an approximately 10% increase in incidences of such relationships compared to simulation runs in which incarceration rates remained at current levels. There are only small changes (mostly slight increases, although we estimate a slight decrease in Baltimore) in these relationships associated with criminal justice reform policies that result in moderate decreases in incarceration rates.

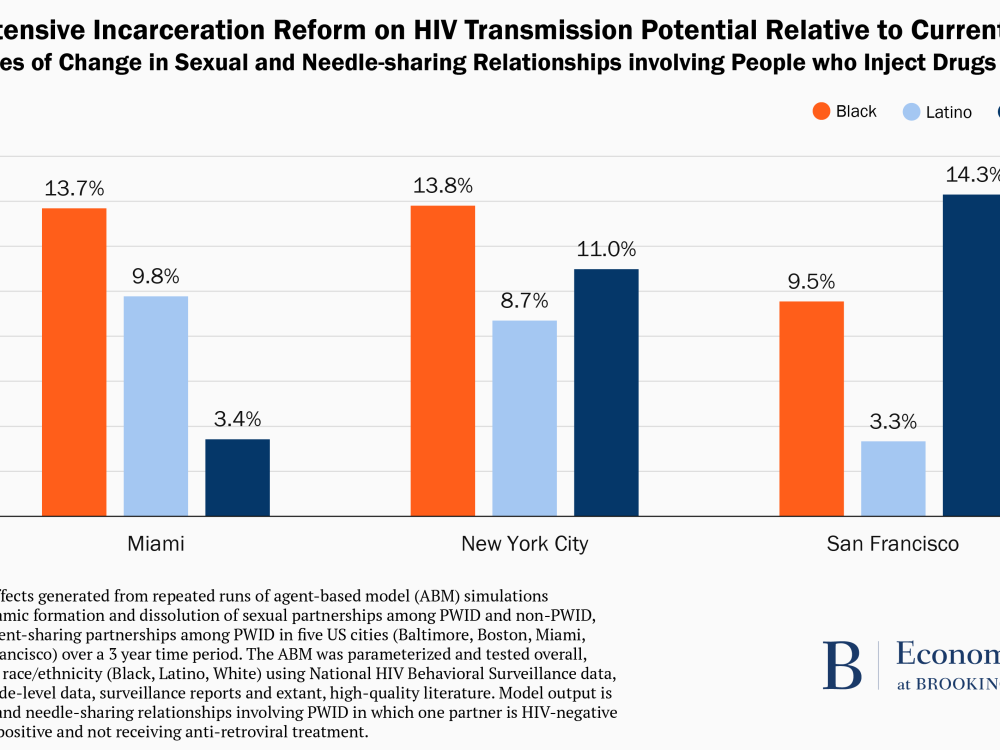

These overall metropolitan area impact estimates can mask some potentially important variation in who is affected. Figure 2 disaggregates the effects of extensive incarceration rate reduction on relationships with the potential for HIV transmission by race in three metropolitan areas. The patterns depicted differ across each of these contexts, with white individuals experiencing the greatest increase in San Francisco and Black individuals in Miami and New York City.

Criminal justice reform initiatives are rooted in efforts to advance social justice and meaningfully enhance racial and ethnic equity. In general, these goals are well-aligned with public health. Thus, the potential for increased spread of HIV resulting from reductions in incarceration rates is counterintuitive. However, this finding should be taken with two important caveats in mind.

The first is that the simulated policy effects are restricted to a relatively short time horizon of three years. Potential positive effects of incarceration reform including decreases in HIV risk behaviors, stabilization of sexual networks, increased access to drug treatment, and HIV care and treatment might eventually offset any initial uptick in community-level HIV prevalence that follows criminal justice reforms.

Second, these simulated effects are absent any concerted efforts to mitigate them. Prior research suggests that ensuring HIV prevention and treatment among justice-involved populations and the persons with whom they interact in the community requires a multipronged approach that accomplishes the following: (1) bridges gaps between HIV and behavioral health services in correctional settings and those in the community, (2) engages formerly incarcerated men and women into HIV testing and treatment, and behavioral health programs in the community, (3) builds trust in the medical system and autonomy among formerly incarcerated men and women, (4) facilitates community reintegration by reducing barriers to employment, housing, and social benefits, leveraging social capital, and (5) integrates case management and patient navigation in post-release and reentry programs. Many of these approaches are documented to have strengthened reintegration and to have increased HIV care engagement and retention. That is, policymakers can proactively and strategically engage in efforts that buffer against unintended, negative consequences of criminal justice reform.

When attempting to limit or prevent increases in HIV prevalence stemming from criminal justice reform, policymakers should keep in mind that “one size does not fit all.” In our simulations, effects of reductions in incarceration rates vary across geographic settings and, within them, across racial and ethnic groups. Therefore, consideration of underlying contextual factors should play a key role in crafting public health strategies that accompany criminal justice reform.

Beyond the immediate implications for criminal justice reform, this work is a good example of the importance of exploring interactions between policy domains rather than only looking at them in isolation. The relationships between areas like health and criminal justice, as well as education, labor, and others, are important and understudied—and often wholly overlooked – to the detriment of policies they govern and people they affect.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Becca Portman assisted with data visualization for this piece.

Commentary

Linking criminal justice reform and health policy: Incarceration rates and HIV prevalence

May 5, 2021