Gender-based violence (GBV) within universities in the global South is a complex, persistent, and unspoken phenomenon that goes largely underreported, under-researched, and under-estimated. The censoring and silencing of women students’ voices along with their hesitancy in coming forward due to fear of reputational harm present important challenges to researching, advocating, and policymaking around the issue. These factors, along with my personal experiences as a victim-survivor of GBV and the ethical and epistemological dilemmas linked to the re-traumatization of survivors in research processes, shaped my decision to adopt a decolonial (an approach that seeks to transform colonial and Eurocentric research practices by repositioning participants at the center of the research and developing alternative ways of learning and knowing) research paradigm when investigating women students’ experiences with GBV at a large public university in India. Specifically, I wanted to prioritize an ethics of care and reciprocity that fostered collaboration, provided comfort to the participants, and supported consciousness-raising throughout the research process.

The use of art-based methods in tandem with narrative interviews helped me prioritize such an ethics of care in the following ways.

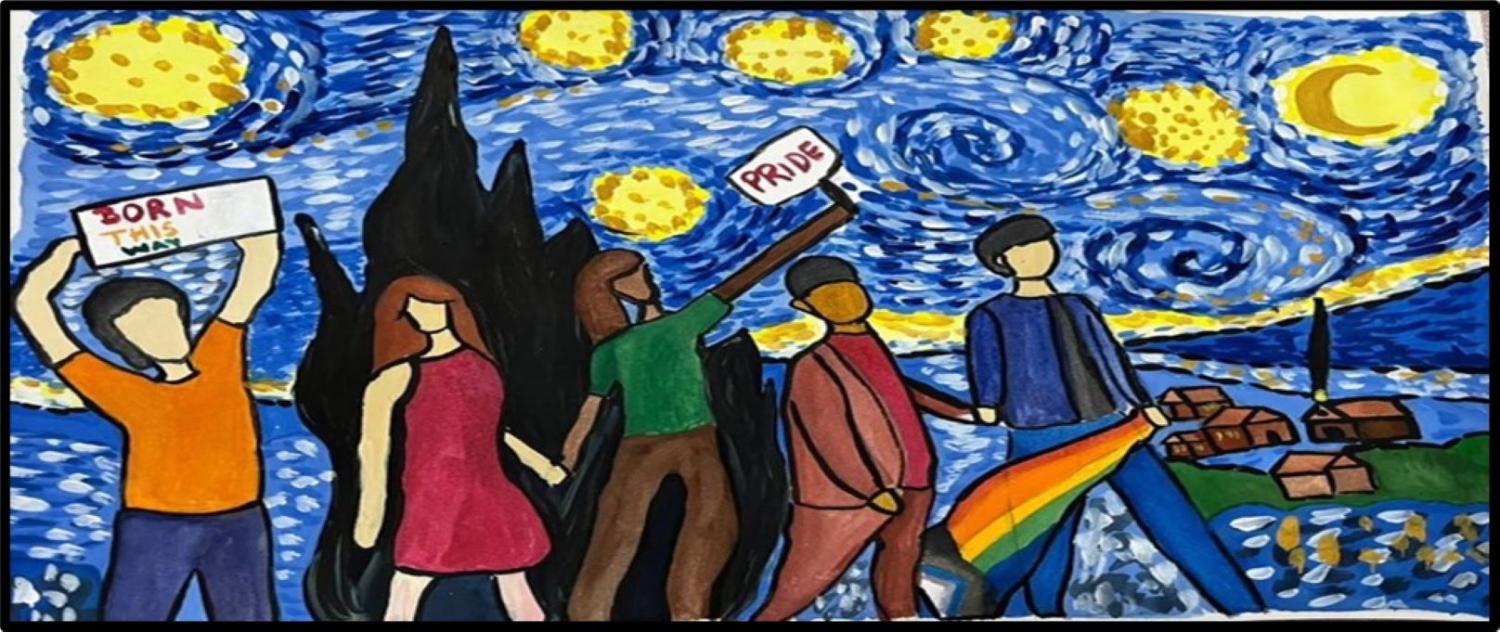

- Provide a comfortable, relaxed, and creative means of expression, thereby making the sensitive topic of GBV less traumatizing for them. In the first stage, self-identified victim-survivors were asked to express their emotions about their experiences via any art form of their choosing (for ex: painting, poetry, sketching, zines, music, etc.), which was later used as an ice-breaker to initiate the narrative interviews. Ahana (pseudonym), a queer student in her final year of college, shared the therapeutic and empowering effect that working on her art form Queer Solidarities had on her. “It had been long that I have sketched something, and to do it about my experiences with GBV as a queer student here, that was just so affirming. [I felt] like someone wanted to listen to me. I cannot wait to discuss my artwork with you tomorrow,” she wrote to me before the interview.

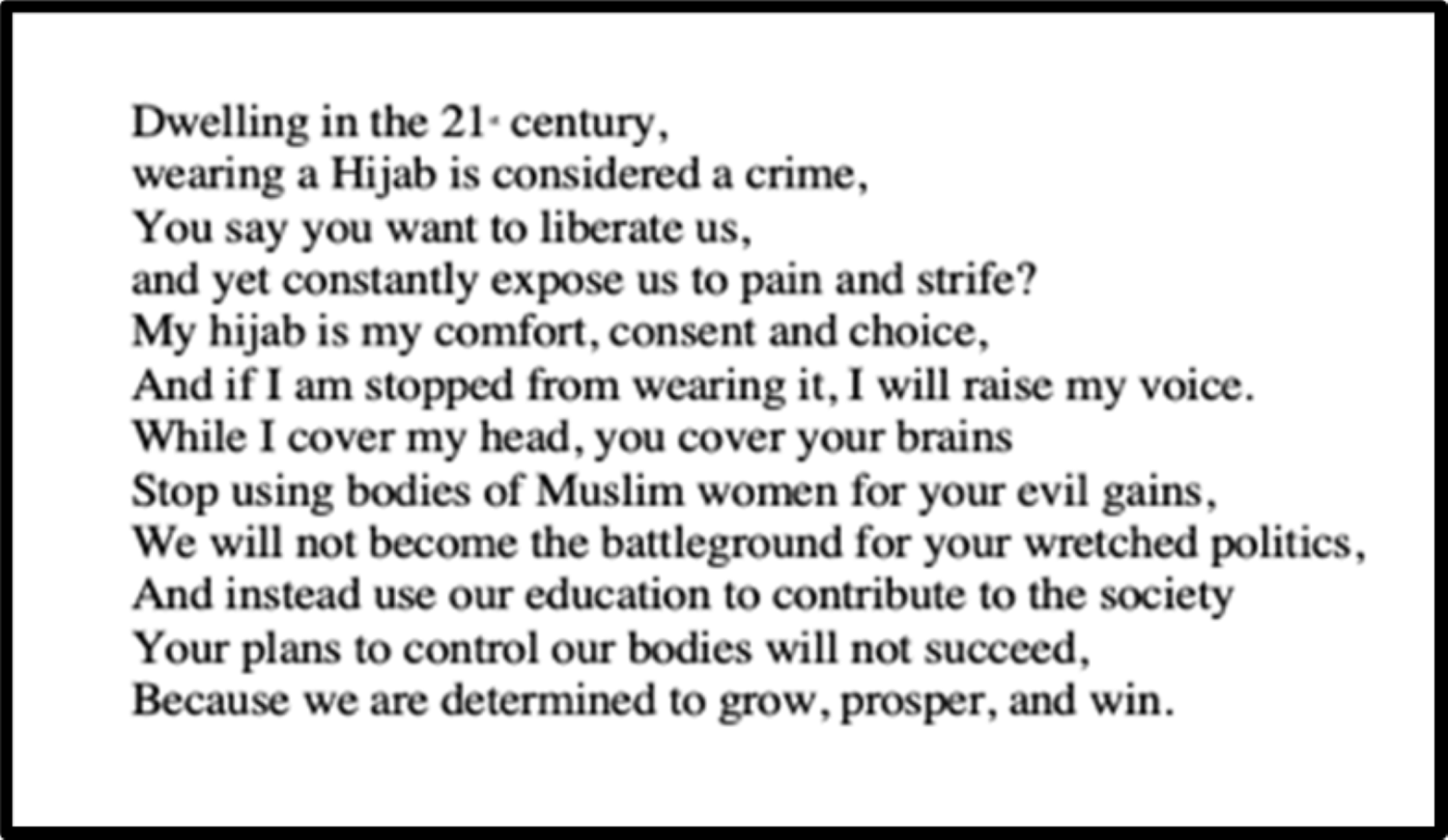

- Build rapport with the participants and minimize the power difference between us. The two-stage process of creating the artwork followed by an interview also helped to do this. I spent a significant amount of time brainstorming the nature, rationale, and scope of their art form with each participant before the interview and personally met with them to answer any questions they might have had about the research or me. In some cases, I also worked collaboratively with them on their art form to better support them in conveying their hopes, aspirations, and concerns, such as in the poem My Hijab, My Choice by Iqra (pseudonym).

- Facilitate a deeper exploration of unsaid gendered power structures and social norms. The reflexivity between the art form and verbalization during the interview helped with this by tapping into the participants’ unconscious, thereby fostering consciousness-raising. For instance, Chayya, a self-identified victim of dating violence, referred to her artwork Why is it Always my Fault? throughout the interview to articulate her experiences with structural gendered inequities linked to slut shaming and victim blaming within Indian society.

Excerpt from the interview with Chayya: “I painted this because in our society, the only and the foremost culprit is the girl, be it from the eyes of our friends, our family, our partner, and not to be forgotten, the so-called ‘society.’ Even parents fail to understand their child because of the fear of the society and choose to stay quiet, no matter how hard times their child is going through.”

An art-based approach to collecting data also supports more innovative avenues for the dissemination of findings to diverse stakeholders such as researchers, policymakers, practitioners, and other community members, which is a critical component of a decolonial research agenda. Within the specific context of my research, I plan to organize a public exhibition of my participants’ art forms at my university in the U.S., as well as across campuses in India to draw local and global attention to the problem of GBV. Other creative means of dissemination of these art forms include interactive websites, conference presentations, online magazines, and participatory workshops.

The use of art-based approaches in conjunction with conventional modes of data collection such as interviews and focus group discussions can prove immensely useful for exploring sensitive topics in education because of their power to decenter hierarchy, foster reciprocity, and support the development and exercise of participants’ agency. At the crossroads of social sciences and humanities, such methods have the capacity to interrogate dominant histories and methodologies. They can also disrupt colonial power dynamics that establish the hegemony of positivistic and quantitative research paradigms by representing alternative modes of learning and knowing. Centering such creative and participatory methodologies also brings us closer to the transformative promise of research linked to collaboration, community building, participant empowerment, and consciousness-raising.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Studying gender-based violence through art: Voices of women students from India

March 5, 2024