“An investment in knowledge pays the best interest.”—Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin, a man of many talents, was also the proud founder of the Library Company of Philadelphia in 1731—the first library in what would become the United States. In his day, libraries offered a conduit to the world, a place to access information, and to discuss and debate the issues of the day. Books were scarce, expensive, and out of reach for most of the population. But for a small fee and with pooled resources, everyone could access paper books, maps, and pamphlets from around the world and become informed and engaged citizens.

Public libraries were the great equalizers, making it possible for people to read the latest tomes on farming to metalworking to foreign affairs, among much more. Philadelphia thus played a key role in leveling the playing field between rich and poor.

Today, the modern Free Library of Philadelphia and other libraries around the world face unique challenges that would be foreign to Franklin. Smartphones, tablets, the internet, and other massive technological changes have reshaped the landscape. Information is easy to access and available to most individuals in their pockets. With a single tap or swipe, we retrieve and discover knowledge that would have taken days or months to find in Franklin’s time.

These changes create a kind of identity crisis for libraries. How do we preserve the essence of a library while being current and forward thinking? Must there be physical books? Should libraries incorporate community-gathering spaces? How important is quiet space and how is it balanced with creating safe spaces for children to learn, play, and discover?

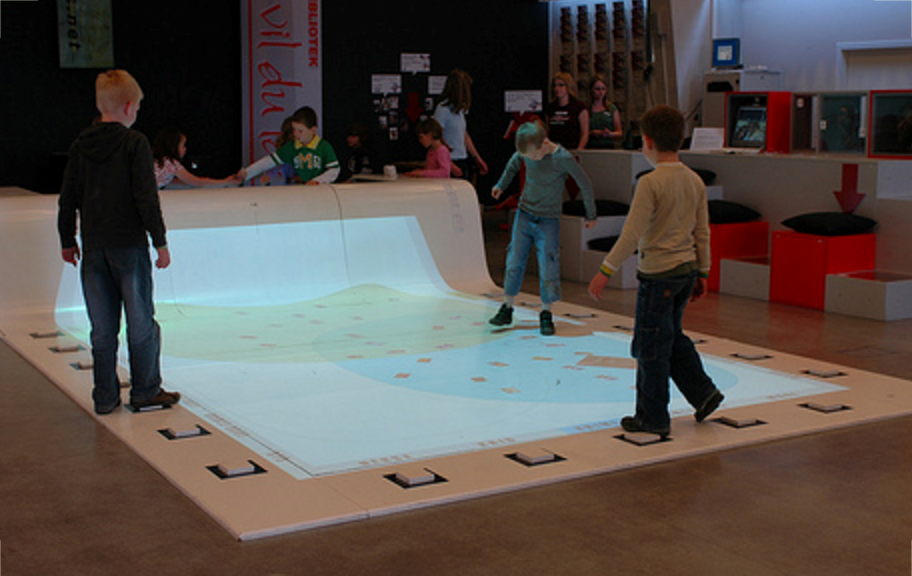

Aarhus Public Libraries in Aarhus, Denmark, provides a vision for a modern library. In the children’s library, researchers from the University of Southern Denmark, ISIS Katrinebjerg, four companies, and five libraries joined together to rethink children’s libraries, looking for ways that 21st century children can interact with their environment and shape their own experiences, particularly with digital media.

In addition to traditional paper books, the transformed children’s library includes activities like Story Surfer, where children physically interact with a story from a paper book on a large screen installed on the library floor. They choose their course of action and explore the book in innovative ways.

Aarhus has changed our view of libraries from being merely places to store information to places that engage children in information and that invite visitors to generate new information. These “maker and hacker” spaces now populate the floors of library spaces around the world. And, interestingly, some of the quiet space has given way to communal gathering and dialogue as in days of old.

Building upon the Aarhus example, we are rethinking the mission of today’s libraries through our Learning Landscapes initiative. Libraries are a perfect example of community spaces where children can spend their out-of-school time. Can we refashion these spaces to support active learning and informal education? Learning Landscapes meets this challenge by transforming city and public spaces into potential venues for learning through interaction. Adopting this lens, we can maintain the essence of a library—as space for information creation and sharing—while enhancing the interactive and engaged components of playful learning.

In Philadelphia, the Free Library—funded by the William Penn Foundation—has developed a project with DIGSAU, Studio Ludo, and Smith Memorial Playground. We joined this team to create playful learning spaces in four different library branches. Paper books will remain, but we are asking how children can interact more with the books they read and the information they want to gather. Could guided play experiences allow children to delve deeper into a literary character’s motivation? Can we image a new way to learn about bridge building and engineering supports by really putting the blocks together to construct those bridges rather than only reading about them? We are asking how the library can embrace some of the newer findings in the science of learning to support 21st century competencies to support the use of collaboration (team building), communication, content (reading, math, and learning to learn skills), critical thinking (problem solving), creative imagination, and confidence (persistence and an “I can do” attitude).

Amidst the hustle and bustle of modern society, libraries remain major hubs where all citizens can access information to generate knowledge—just as Benjamin Franklin envisioned. But, in Philadelphia, we are spearheading a movement to reimagine libraries by asking how to do we keep the essence of “library” while embracing new avenues for information gathering, knowledge construction, and public assembly. It is in this spirit that we remain guided by Franklin’s insights. Libraries must continue to be hubs for accessing information, but in a 21st century global environment, libraries can become active learning spaces that also encourage interactive discovery and places where dialogue and debate is welcome. Learning Landscapes can help us rethink libraries in ways that bring Franklin’s 300-year-old vision to light in the modern era.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Lessons from Ben Franklin: Using learning landscapes to rethink modern libraries

March 21, 2017