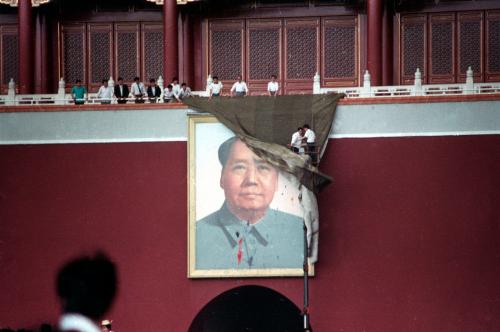

Thirty years after the cataclysms of the Tiananmen massacre, the human rights situation in China remains dire. Space for dissent has shrunk, many parts of civil society have become stifled, and room for religious observance has been squeezed. An unknown but very large number of Uighurs are being “re-educated” in camps across Xinjiang without due process. Tibet’s unique culture is being trampled. Beijing has cultivated a climate of fear with an increasingly sophisticated surveillance state that is burrowing into every corner of the country, creating what some now describe as a model of “digital authoritarianism.”

At times like these, it is tempting to grow jaded about the prospects for change inside China. That would be a mistake. For the U.S. policy community, reflection is warranted, but resignation is not.

Beijing’s increasing heavy-handedness is more a symptom of fear than strength. It is borne in part from anxiety about the global trend of power diffusing from governments to non-state actors, a development that runs against the Communist Party’s desire to keep a tight grip on society. It also arises out of the Communist Party’s deep-seated concern that its legitimacy will come under scrutiny, particularly as economic growth continues to decelerate. Beijing’s endemic challenges in enforcing discipline within the Communist Party, particularly as it relates to corruption, also arouses anxieties. So, too, does latent admiration within Chinese society for values that America has sought to advance, even as popular views of the United States government come under fresh scrutiny.

Change inside China will occur on China’s timelines, not ours.

Against this backdrop, American policymakers would be wise to approach China human rights questions with humility. Change inside China will occur on China’s timelines, not ours. Social engineering of foreign societies is not an American strength. The United States is no more capable of compelling political or social change inside China than it has been in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, or Venezuela. And it would be reckless for the United States to assume or attempt otherwise.

American policymakers also must contend with the fact that President Trump is indifferent to human rights issues in China, and Beijing knows it. No amount of advocacy from the vice president or others will obscure this reality. In the absence of presidential prioritization, there will be a low ceiling on the amount of influence Washington is able to exercise, both in direct dealings with Beijing and in efforts to coordinate approaches with allies and partners.

Even so, important work can still be done. U.S. diplomatic posts in China can continue to honor the memories of the students that sacrificed their lives 30 years ago around Tiananmen Square, as well as others that followed in their footsteps, such as Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo. It can do so by using anniversaries and other occasions to highlight the ideals they cherished and the vision they sought for China. American diplomats can continue to keep faith with brave Chinese advocates of rights protections who get crosswise with China’s security services by attending their court hearings, or by standing as a symbol of support outside of courthouses when they are barred from entry.

American organizations can support Chinese grassroots efforts to improve quality of life inside the country. Previously, the U.S. Embassy in Beijing raised public awareness about air pollution by broadcasting daily readings of PM2.5 levels. This, in turn, empowered a constituency of Chinese citizens concerned about their health and the health of their children, leading them to demand that Chinese authorities improve air quality. And they did.

It is in America’s interests for Chinese authorities to translate their anxieties about performance legitimacy into concrete actions that improve the lives of their citizens. There may be similar scope for efforts around issues such as food safety, intellectual property rights protections, equal access to education, and rule of law and due process protections.

The most crucial step the United States can take, though, is to restore the power of its own example. America’s ability to attract support for the values it promotes is being eroded by the growing gap between rhetoric and reality at home. America’s influence is greatest when it is open, prosperous, and true to its ideals.

By the same token, the United States needs to stay focused on the long game, including by inspiring the next generation of Chinese citizens. If we barricade ourselves against Chinese visitors and students, as well as Chinese trade and investment, we will breed a generation of Chinese who are more hostile to the United States. There are instances when the United States must draw lines to protect its own security. That is every government’s right and responsibility. At the same time, no American leader should speak in racial terms about “whole-of-society” threats from other countries. Such comments betray the ideals upon which the United States was founded and learn nothing from dark periods in America’s past.

With modesty, persistence, and patience, the United States can still play an important role in encouraging China down a path toward greater freedoms for its people. Such an outcome would help unlock the full talents of the Chinese people, a goal that would serve both countries’ long-term interests.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Lessons for raising human rights issues with Beijing

May 29, 2019