On the afternoon of Saturday, June 3, 1989, in the midst of my weekend routine in suburban Washington, I received a phone call from Pei Minxin, who was then a graduate student in the United States at Harvard. He called to say that he was receiving panicked reports from Beijing that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regime was engaged in a violent crackdown of public protests in Beijing, in order to end the occupation of Tiananmen Square. Minxin, who now teaches at Claremont University, had contacted me because I worked on the staff of the Asia Subcommittee of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. Indeed, he had testified at a subcommittee hearing on the unrest in China only weeks before.

Minxin hoped that I could do something to generate a U.S. government response to the carnage that was underway. Sadly, there was nothing that I or any other American could do, since the Chinese leadership had embarked on the path of suppression weeks before. Where I did play a modest role was in the congressional response to the Tiananmen tragedy.

The view from Capitol Hill

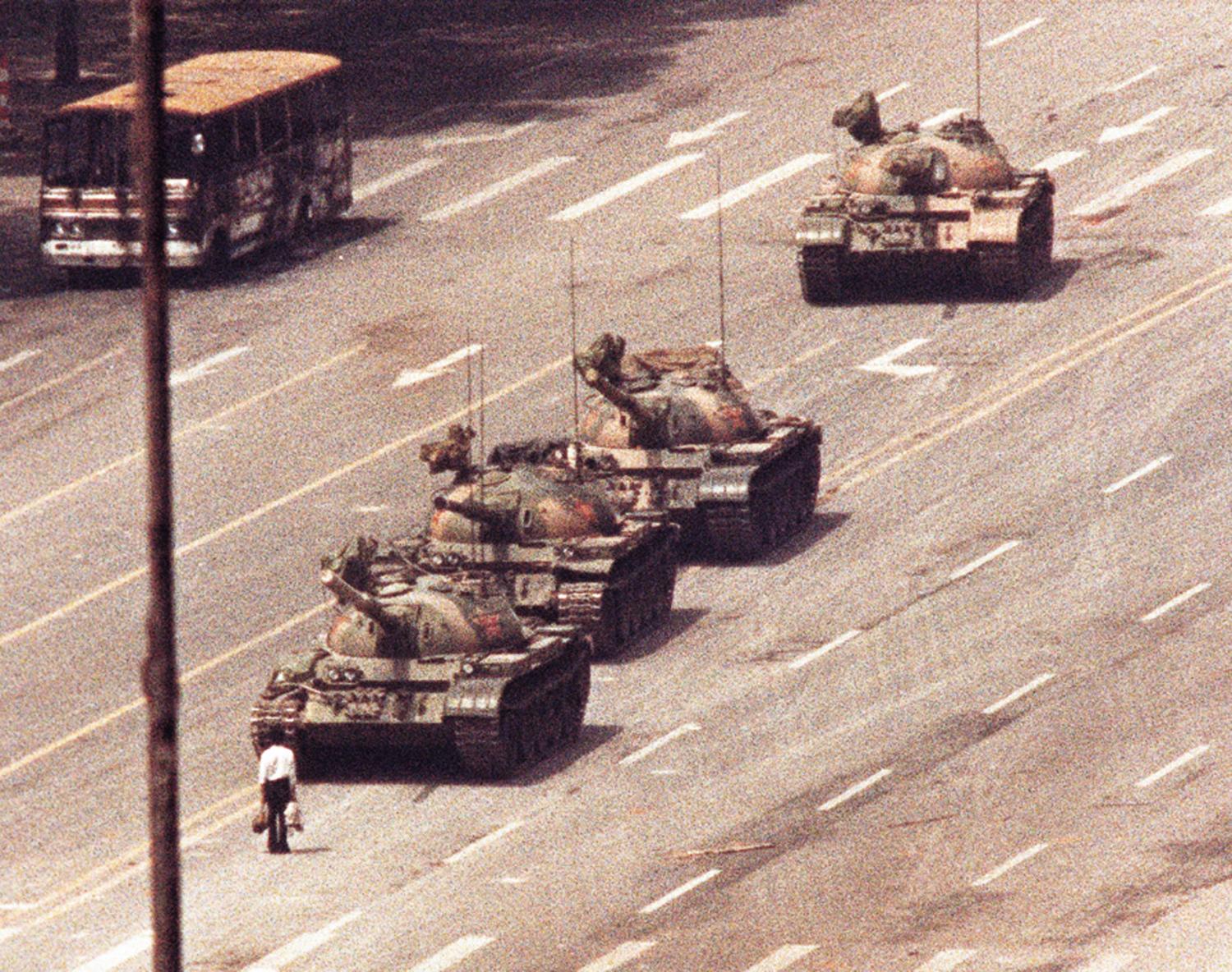

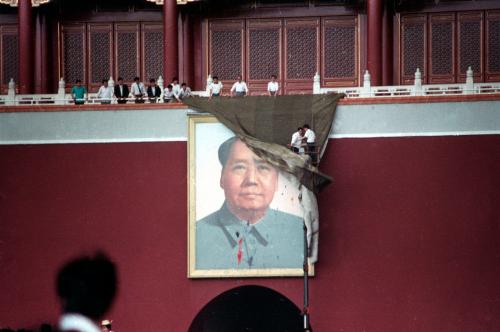

Members of Congress and the American public were exposed to this critical episode in modern Chinese history because of television. It happened that Mikhail Gorbachev was scheduled to visit China in mid-May for a summit with Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, so the three broadcast networks were already deployed to cover that story and then found themselves in the middle of a much more exciting event. Tiananmen provided the debut for Ted Turner’s Cable News Network (CNN) and its 24/7 approach to covering the world. American journalism would never be the same. The image of a young man standing in front of an army tank remains iconic to this day.

The crackdown a few days later changed congressional attitudes about China. The most disturbed were liberal members who had believed that China’s economic opening and the gradual relaxation of the CCP’s grip over Chinese society would slowly and ultimately lead to positive political change. Conversely, conservatives were not surprised at all. Tiananmen was proof-positive of their belief that the communist regime was still a repressive dictatorship. What had changed was the CCP’s willingness to display its true nature for all to see.

Congress quickly looked for ways to respond to the shock and horror that Tiananmen produced. It felt that the George H. W. Bush administration was too tepid in its response, and many members criticized the administration harshly. But Congress was constrained by its lack of leverage over executive branch policy and the conflict among U.S interests.

From the outset of the crisis, members received appeals from constituents who had relatives in China. They were generally frustrated with what they regarded as slow action by the State Department and U.S. diplomatic posts in China to evacuate American citizens. Yet members underestimated the many tasks that a limited number of U.S. diplomats had to perform in a dangerous situation and the operational difficulties of running a large evacuation.

Second, a number of members of Congress, especially those whose districts and states included major universities, were approached by Chinese students who were afraid to return to China once their visas expired. Quickly, legislation was drafted and soon passed to allow Chinese students to extend their stays in the United States. President Bush ultimately vetoed the bill but simultaneously issued an executive order that accomplished the same thing. The person who took the lead on this initiative was a new member from the San Francisco Bay area, Nancy Pelosi.

Third, and more complicated, was what should be done legislatively to restrict the U.S. relationship with China in response to the CCP’s violent crackdown against its own people. Although the Bush administration had taken some steps immediately, members of Congress believed that more was necessary. But the options were limited because any steps taken had to be within Congress’s prerogatives.

In July 1989, the House of Representatives included a package of sanctions on China in a broader bill. These banned or restricted arms sales, crime control equipment, and technology transfers, and shifted the U.S. government’s stance to restrict loans to China by international financial institutions. Included was authority for the president to waive the sanction if it was in the “national security interests” of the United States, a pretty high standard. The Senate passed its version of the bill in early 1990, weakening the waiver authority to U.S. “national interests” only. The bill soon became law.

The one sanction that was not considered until 1991, for technical reasons, was rejecting or conditioning the president’s annual extension of China’s most-favored-nation (MFN) trading status. Without those extensions, Chinese exports would have to pay the onerous tariffs from the Smoot-Hawley era. But by 1991, the technical problems were fixed and a coalition of liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans, led by Rep. Pelosi and Senator George Mitchell, drafted a bill that would link China’s human rights, economic, and proliferation policies to the annual extension of its MFN status.

The bill passed both houses of Congress and was vetoed by President Bush. The House then overrode the veto but the Senate, by a narrow margin, sustained it. A similar bill was passed in 1992, with the same result. At each stage of the legislative process, human rights groups, Chinese students, and other critics of China favored conditionality while American corporations, senior foreign policy statements, and Hong Kong interests were opposed.

The (ongoing) politics of human rights promotion

Tiananmen continued to haunt American politics in the 1992 election campaign. Candidate Bill Clinton called out the “butchers of Beijing” and vowed, if elected, to condition his extension of China’s MFN status. After taking office, in May 1993, President Clinton extended MFN but also issued an executive order setting conditions on China that would govern his 1994 decision. There ensued an intense, high-stakes campaign by U.S. diplomats to get Beijing to accept Clinton’s conditions.

But the Chinese government played on the anxieties of the American business community, which had not originally opposed the executive order. By the end of 1993, American companies became deeply concerned that Beijing would not meet its conditions and that their competitive position in China would be in jeopardy. They believed that Deng Xiaoping’s reinvigoration of economic reform and opening up, which he began in 1992, would work to their strong advantage, but that denying China MFN status would put at risk the entire future of their companies and the jobs they created. (Note that many American companies now believe that Chinese economic policy has moved into a predatory mode, and that it is excessive dependence on the China market that puts their future at risk.)

Caught between contending forces, Clinton in May 1994 decided to abandon the linkage policy and try to advance human rights in China through different means. Nancy Pelosi felt betrayed and introduced conditionality legislation. But the political landscape in the United States had changed. U.S.-China economic interdependence had deepened. A bipartisan, centrist coalition mobilized to oppose the legislation (Rep. Lee Hamilton, for whom I worked at the time, was a leader of that coalition).

In August 1994, five years and two months after the Tiananmen tragedy, the House of Representatives voted down the Pelosi bill. How to promote democracy and human rights in China, always a fraught issue, was—and is—subject to the dynamics of America’s own democratic system.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

30 years after Tiananmen Square, a look back on Congress’ forceful response

May 29, 2019