What’s happening to American matrimony? In 1960, more than 70 percent of all adults were married, including nearly six in ten twentysomethings. Half a century later, just 20 percent of 18-29-year olds were hitched in 2010. Marriage was the norm for young America. Now it’s the exception.

American marriage is not dying. But it is undergoing a metamorphosis, prompted by a transformation in the economic and social status of women and the virtual disappearance of low-skilled male jobs. The old form of marriage, based on outdated social rules and gender roles, is fading. A new version is emerging—egalitarian, committed, and focused on children.

There was a time when college-educated women were the least likely to be married. Today, they are the most important drivers of the new marriage model. Unlike their European counterparts, increasingly ambivalent about marriage, college graduates in the United States are reinventing marriage as a child-rearing machine for a post-feminist society and a knowledge economy. It’s working, too: Their marriages offer more satisfaction, last longer, and produce more successful children.

The glue for these marriages is not sex, nor religion, nor money. It is a joint commitment to high-investment parenting—not hippy marriages, but “HIP” marriages. And America needs more of them. Right now, these marriages are concentrated at the top of the social ladder, but they offer the best—perhaps the only—hope for saving the institution.

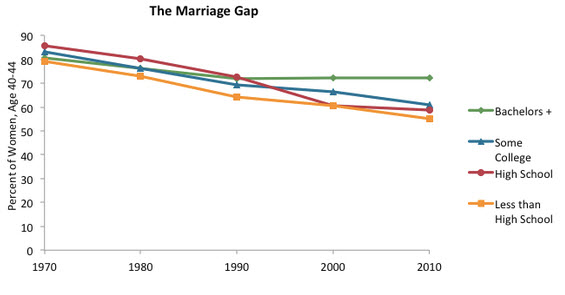

The Marriage Gap

Matrimony is flourishing among the rich but floundering among the poor, leading to a large, corresponding “marriage gap.” Women with at least a BA are now significantly more likely to be married in their early 40s than high-school dropouts:

During the 1960s and 1970s, it looked as if the elite might turn away from this fusty, constricting institution. Instead, they are now its most popular participants. In 2007, American marriage passed an important milestone: It was the first year when rates of marriage by age 30 were higher for college graduates than for non-graduates. Why should we care about the class gap in marriage? First, two-parent households are less likely to raise children in poverty, since two potential earners are better than one. More than half of children in poverty—56.1 percent, to be exact—are being raised by a single mother.

2007 was the first year in American history when marriage rates were higher for college grads than non-grads, over the age of 30.

Second, children raised by married parents do better on a range of educational, social and economic outcomes. To take one of dozens of illustrations, Brad Wilcox estimates that children raised by married parents are 44% more likely to go to college. It is, inevitably, fiendishly difficult to tease out cause and effect here: Highly-educated, highly-committed parents, in a loving, stable relationship are likely to raise successful children, regardless of their marital status. It is hard to work out whether marriage itself is making much difference, or whether it is, as many commentators now claim, merely the “capstone” of a successful relationship.

Three Kinds of Marriage

The debate over marriage is also hindered by treating it as a monolithic institution. Today, it makes more sense to think of “marriages” rather than “marriage.” The legalization of same-sex marriages is only the latest modulation, after divorce, remarriage, cohabitation, step-children, delayed child-bearing, and chosen childlessness.

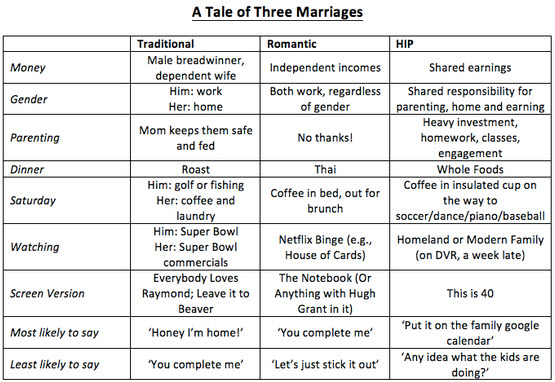

But even among this multiplicity of marital shapes, it is possible to identity three key motivations for marriage—money, love, and childrearing—and three corresponding kinds of marriage: traditional, romantic, and parental (see Box).

Traditional marriage is being rendered obsolete by feminism and the shift to a non-unionized, service economy. Romantic marriage, based on individual needs and expression, remains largely a figment of our Hollywood-fueled imaginations, and sub-optimal for children. HIP marriages are the future of American marriage—if it has one.

1. Traditional Marriage: Going, Going…

The traditional model of marriage is based on a strongly gendered division of labor between a breadwinning man and a homemaking mom. Husbands bring home the bacon. Wives cook it. In these marriages, often underpinned by religious faith, duty and obligation to both spouse and children feature strongly. In their ideal form, traditional marriages also institutionalize sex. Couples wait until the wedding night to consummate their relationship, and then remain sexually faithful to each other for life.

Attempting to restore this kind of marriage is a fool’s errand. The British politician David Willetts says that conservatives are susceptible to “bring backery” of one kind or another. Many conservative commentators on marriage fall prey this temptation: To restore marriage, they say, we need to bring back traditional values about sex and gender; bring back “marriageable” men; and bring back moms and housewives.

It is too late. Attitudes to sex, feminist advances, and labor market economics have dealt fatal blows to the traditional model of marriage.

Sex before marriage is the new norm. The average American woman now has a decade of sexual activity before her first marriage at the age of 27. The availability of contraception, abortion, and divorce has permanently altered the relationship between sex and marriage. As Stephanie Coontz, the author of Marriage, A History and The Way We Never Were, puts it, “marriage no longer organizes the transition into regular sexual activity in the way it used to.”

Feminism, especially in the form of expanded opportunities for women’s education and work, has made the solo-breadwinning male effectively redundant. Women now make up more than half the workforce. A woman is the main breadwinner in 40% of families. For every three men graduating from college, there are four women. Turning back this half century of feminist advance is impossible (leaving aside the fact that is deeply undesirable).

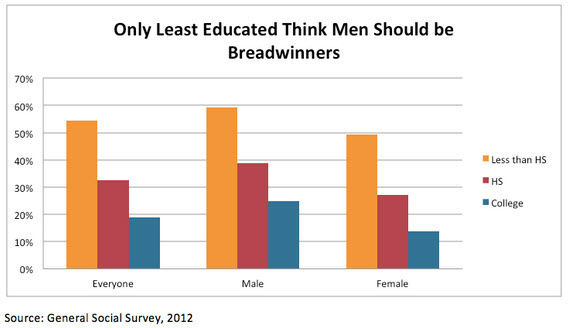

There is class gap here, however. Obsolete attitudes towards gender roles are taking longest to evolve among those with the least education.

The bitter irony is that those most likely to disdain female breadwinners (the least educated men and women) would be helped the most by dual-earner households. The men who want to be breadwinners are very often the ones least able to fill that role.

Traditional marriage, then, is being undermined on all sides. Most Americans think marriage is not necessary for sexual fulfillment, personal happiness, or financial security, according to Pew Research. They’re right.

2. Romantic Marriage: Great for a While, but for Whom?

What about love?

If the breadwinner-housewife model for marriage is dying, there is still a romantic model. This is a version of marriage based on spousal love—as a vehicle for self-actualization through an intimate relationship, surrounded by ritual and ceremony: cohabitation with a cake.

Many scholars worrying about the decline of marriage point to a shift from stable, traditional marriages to disposable, romantic ones—what Andrew Cherlin, Brad Wilcox and others describe as a “deinstitutionalization” of marriage. After studying relationships in poor Philadelphia neighborhoods, Kathryn Edin and Maria Kefalas concluded that “marriage is a form of social bragging about the quality of the couple relationship, a powerfully symbolic way of elevating one’s relationship above others in a community, particularly in a community where marriage is rare.” More recently, Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers have suggested that the family has shifted from being “a forum for shared production, to shared consumption.” As a consequence, marriage has become a “hedonic”relationship that is “somewhat less child-centric that it once was.”

Half of unmarried new parents are in a new relationship by the time that child starts kindergarten.

Romantic marriages are ideal for Hollywood, and ideal for many couples, but they are not ideal for raising children, for the simple reason that the focus is on the adult relationship, not the parent-child relationship. Romantic marriages are passionate, stimulating, and sexy. Parenting, by contrast, involves hard physical labor, repetitive tasks, and exhaustion.

Even when divorced parents re-marry, the negative effects on children can be detected, perhaps because the necessary investment in a new relationship “crowds out” investment in the children. (Half of the parents unmarried at the birth of their child are in a new relationship by the time they start kindergarten.) These parents are engaged in the intense emotional work of building a new adult relationship, at a time when their children may need them the most. It is hard to have sleepless nights with a new lover when you are having sleepless nights as a new mother.

3. HIP Marriages: It’s About the Kids

Given the obsolescence of traditional matrimony and the shortcomings of romance (for children, at any rate), it is easy to predict a slow death for marriage. In fact, we can see marriage persisting among the most affluent and educated Americans. But they’re not going back to the old model their parents rejected. They are creating a new model for marriage—one that is liberal about adult roles, conservative about raising children.

The central rationale for these marriages is to raise children together, in a settled, nurturing environment. So, well-educated Americans are ensuring that they are financially stable before having children, by delaying childrearing. They are also putting their relationship on a sound footing too—they’re not in the business of love at first sight, rushing to the altar, or eloping to Vegas. College graduates take their time to select a partner; and then, once the marriage is at least a couple of years old, take the final step and become parents. Money, marriage, maternity: in that order.

By delaying childbearing, these new-model spouses can actually get the best of both worlds, enjoying the benefits of a romantic marriage, before switching gears to a HIP marriage once they have children. This means the relationship has some built-in resilience before entering the “trial by toddler” phase–and also, that emotional investment in the children can take priority for the next few years, following years of investment in each other. Many couples manage a “date night” every week or so–but every night is parenting night. Indeed, there is some evidence that there is less sex in these egalitarian, child-focused marriages. But least for this chapter of the relationship, sex is not what they’re about.

The HIP Formula: Conservative About Kids …

Married, well-educated parents are pouring time, money and energy into raising their children. This is a group for whom parenting has become virtually a profession.

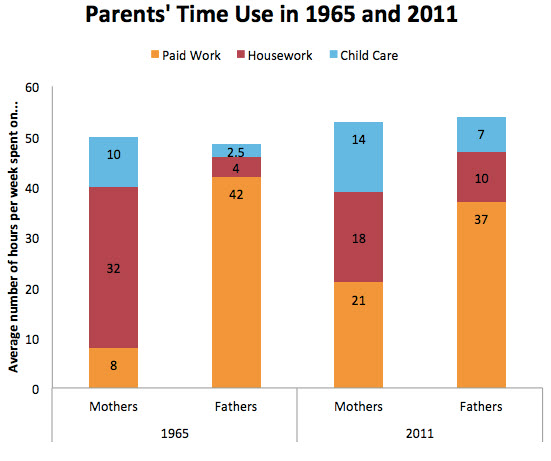

When it comes to the most basic measure of parenting investment—time spent with children—a large class gap has emerged. In the 1970s, college-educated and non-educated families spent roughly equal amounts of time with their children. But in the last 40 years, college-grad couples have opened up a wide lead, as work by Harvard’s Robert Putnam (of Bowling Alone fame) shows. Dads with college degrees spend twice as much time with their children as the least-educated fathers.

Although college graduates tend to be a reliably liberal voting bloc, their attitudes toward parenting are actually quite conservative. College grads are now the most likely to agree that “divorce should be harder to obtain than it is now” (40%), a slight increase since the 1970s. Although we can’t be sure why, this is likely connected to the accumulating evidence that single parenthood provides a steep challenge to parenting.

College grads are conservative on divorce and child-rearing, egalitarian on gender roles, and liberal on social issues.

On the opposite end of parenting too little, there has developed a small backlash against over-parenting and child-centered marriages. Perhaps a few parents are overdoing it. We don’t really know. But we do know that engaged, committed parenting is hugely important. Simply engaging with and talking to children has strong effects on their learning; reading bedtime stories accelerates literacy skill acquisition; encouraging physical activity and feeding them balanced meals keeps them healthy, strong and alert. Marriage is becoming, in the words of Shelly Lundberg and Robert Pollak, a “co-parenting contract” or “commitment device” for raising children:

“The practical significance of marriage as a contract that supports the traditional gendered division of labor has certainly decreased: our argument is that, for college-educated men and women, marriage retains its practical significance as a commitment device that supports high-levels of parental investment in children.” Scholarly disputes over whether marriage causes or merely signals better parenting miss the point. As a commitment device, HIP marriages do not cause parental investments—but they do appear to facilitate them. Forthcoming work from Brookings suggests that stronger parenting is the biggest factor explaining the better outcomes of children raised by married parents.

… But Liberal About Relationships

The HIP model of marriage, then, is built on a strong, traditional commitment to raising children together. But in other respects it differs sharply from the traditional model. Most importantly, the wife is not economically dependent on the husband. HIP wives have a good education, an established career, and high earning potential. We cannot understand modern marriage unless we grasp this central fact: The women getting, and staying, married are the most economically independent women in the history of the nation. Independence, rather than dependence, underpins the new marriage.

Of course, affluent couples may decide that for a period, one parent will devote more of their time to parenting than to career, especially when the children are young. If the mother takes some time out, these marriages masquerade, briefly, as traditional ones: a breadwinning father, a home-making mother, and a stable marriage.

But HIP marriages are actually recasting family responsibilities, with couples sharing the roles of both child-raiser and money-maker. There will be lots of juggling, trading and negotiating: “I’ll do the morning if you can get home in time to take Zach to baseball.” Since the 1960s, fathers have doubled the time they spend on housework and tripled their hours of childcare.

Source: Modern Parenthood: Roles of Moms and Dads Converge as They Balance Work and Family, by Kim Parker and Wendy Wang, Pew, 2013.

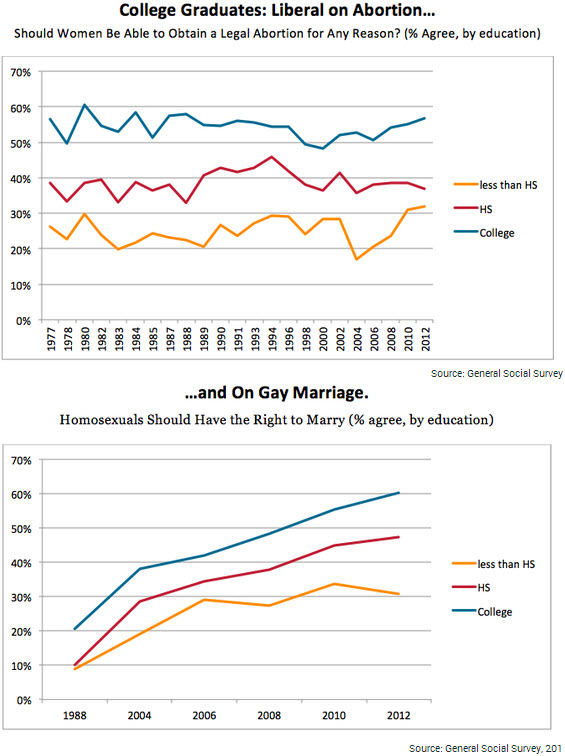

College graduates are more likely to approve of women working, for example, even when her husband’s “capable of supporting her.” The greater liberalism of well-educated Americans extends beyond gender roles, too. Compared to less educated Americans, for example, college graduates are more liberal about abortion, pre-marital sex, legal marijuana, and gay marriage.

So: College grads are highly conservative when it comes to divorce and having children within marriage; but the most egalitarian about gender roles; and the most liberal about social issues generally.

Saving Marriage For the Poor

Most Americans support marriage, most Americans want to get married, and most Americans do get married. Why then is the institution atrophying among those with least education and lowest incomes?

A lack of “marriageable” men is a common explanation. It is clear that the labor market prospects of poorly-educated men are dire. But the language itself betrays inherent conservatism. “Marriageability” here means, principally, breadwinning potential. Nobody ever apparently worries about the “marriageability” of a woman: Presumably she just has to be fertile.

If a man can’t earn—and that’s apparently his only authentic contribution—he becomes just another mouth to feed, another child. But men with children are something more than just potential earners: They are fathers. And what many children in our poorest neighborhoods need most of all is more parenting.

The simple, sad truth is that this nation faces a deficit of fathers.

The proportion of children being raised by a single parent has more than doubled in the last four decades. Most black children are now being raised by a single mother. Mass incarceration plays a role here: More than half of black men without a high school degree do some jail time before they turn 30. In short, the nation faces a fathering deficit. By continuing to see the male role in such constricting terms—as breadwinner or nothing—we are inadvertently contributing to the slow death of marriage in our most disadvantaged communities.

Here, the traditional marriage needs to be turned on its head. In many low-income families, it is the mother who has the best chance in the labor market. But this doesn’t make men redundant. It means men need to start doing the “women’s work” of raising kids. Although there is a lingering determinism about parenting and gender roles, recent evidence—in particular from Ohio State University sociologist Douglas B. Downey—suggests that women have no inherent competitive advantage in the parenting stakes.

The children who can benefit most from high levels of parental investment, from both mom and dad, are the poorest. HIP marriages are an elite invention that could make the greatest difference in the poorest communities, if only attitudes can be shifted. Our central problem is not the slow retreat of the idea of traditional marriage. It is the stubborn persistence of the idea of traditional marriage among those people for whom it has lost almost all rationale.

To Promote Marriage, Promote Parenting

The debate about America’s “marriage crisis” focuses on failure—on the forces working to undermine marriage, especially in the poorest communities. It would serve our purposes better to turn our attention to success. Against all predictions, educated Americans are rejuvenating marriage. We should be spreading their successes. Given the implications for social mobility and life chances, we should be striving to accelerate the adoption of new marriages further down the income distribution.

Perhaps propaganda—or, more politely, social marketing—has a role to play. The elites running our public institutions aren’t abandoning marriage: but maybe they aren’t encouraging it either. In Coming Apart, the social analyst Charles Murray accuses the affluent of failing to “preach what they practice”:

“The new upper class still does a good job of practicing some of the virtues, but it no longer preaches them. It has lost self-confidence in the rightness of its own customs and values, and preaches nonjudgementalism instead. [They] don’t want to push their way of living onto the less fortunate, for who are they to say that their way of living is really better? It works for them, but who is to say it will work for others? Who are they to say that their way of living is virtuous and others’ ways are not?”

Murray casts the new marriage as a reversion to old virtues, especially religion. That’s wrong. HIP marriages are based on a new virtue, appropriate for the modern economy: heavy investment in children. More important, it is hard to know what Murray wants from the “new upper class.” What would it mean to “push their own way of life onto the less fortunate”?

The idea that marriage can be anything other than a freely-chosen commitment is medieval. Americans, in particular, react badly to the government passing judgment on voluntary relationships between adults: that’s one reason the bar on gay marriages has gone. And as it happens, Bush-inspired policies to promote marriages have had little success. What we need is a not a Campaign for Marriage, but a Campaign for Good Parenting, which may, as a byproduct, bring about a broader revival of marriage.

The Polish anthropologist Bronislaw Malinoski once described marriage as a means of tying a man to a woman and their children. Nowadays, women don’t need to be tied to a man. Sex and money can be found outside the marital contract. But children do need parents—preferably loving, engaged parents. Indeed they may need them more than ever. In 21st century America, nobody needs to marry, although many will still choose to. Recast for the modern world, and re-founded on the virtue of committed parenting, marriage may yet have a future. That future of marriage matters most for the individuals in the house that aren’t in the union: our children.

Commentary

How to Save Marriage in America

February 13, 2014