Stagnant median wages and income inequality are two of the most central economic challenges facing the United States. Yet income data represents only the revenue side of the ledger for American families.

The other side of the budget—expenditures—is also important. And on this front the price of consumer goods and services is particularly important because low- and middle-class families spend a larger share of their income on consumption than the wealthy.

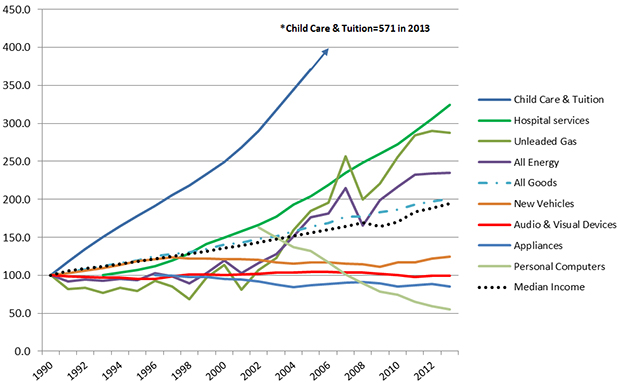

So what’s going on with prices? Recent data from the Consumer Price Index—an index of the change in the prices of goods and services—show that the prices of a number of products and services have actually declined in relation to median income. For example, while median income has grown annually by 2.8 percent since 1990, the average price of durable goods has declined by .01 percent a year. Computers, information technology services, and appliances are all cheaper today than 25 years ago, while the price of automobiles has grown by less than a percentage point annually. Today it takes fewer hours of work for a middle income wage earner to afford a car than at any time in history. These price declines constitute unequivocal wins for the American middle and working classes.

Unfortunately this isn’t the whole story. The prices of a number of good and services have outpaced median income. For example, the price of hospital services and child care and tuition has grown by an astounding 200 percent faster than median wage. Prices have outpaced income in housing rental, legal and professional services, and hotels and lodging as well. These large sectors and the high prices they charge are contributing heavily to the slipping economic position of American households.

Figure One: Median Income and Change in Price of Select Goods 1990-2013 (1990=100)

Source: Authors calculations of Bureau of Labor Statistics data (price data for personal computers, hospital services, and appliances were only available beginning in 1993, 2002 and 1996, respectively)

Firms in these industries differ from those in the technology sector in that they are neither investing heavily in innovation nor competing internationally. For example, the automotive, IT, and software industries invested over 9 percent of sales in R&D last year, while the non-traded services sector like health care and education invested less than 0.7 percent. The reality is, in the moderate- and long-run, only by investing in novel techniques, machines, and production processes can firms maintain global competitiveness, keep jobs in the United States, and lower prices.

There is growing concern that we’re entering an era where technology and economic wellbeing for the average worker has become decoupled. And we know the price of a new dishwasher will never be low enough for a worker who has lost her job. But the alternative is equally untenable; the industries that have not invested in innovation are hammering families by ever-rising prices. For this reason alone an innovation-based economy should be seen as a necessary part of an American economy that works for middle and low-wage earners.

Commentary

How Does Innovation Support Lower and Middle Class Families? Look to the Price Index

November 25, 2014