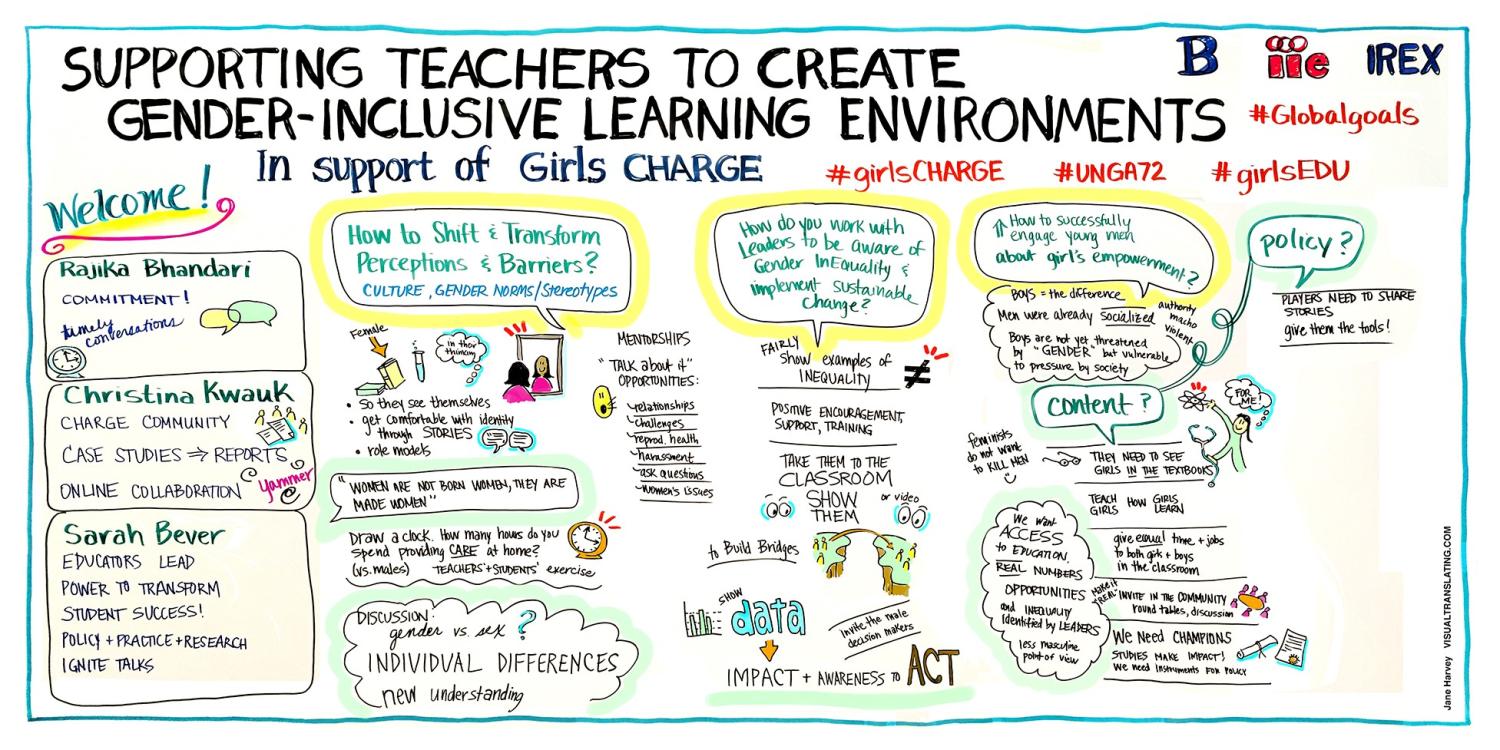

This blog highlights discussions made during a Girls CHARGE event, a girls’ education community of practice, co-hosted by the Center for Universal Education, IIE, and IREX on the margins of the U.N. General Assembly in September.

When asked what gender issues in education Thailand was concerned about, a high-ranking education official replied, “There are no gender issues here—equal numbers of girls and boys are enrolled in our schools.” After he visited several classrooms and observed the gendered practices of teachers (e.g., calling on more boys than girls, asking boys more difficult questions than girls) the surprised official exclaimed: “It looks like we do have some things to work on here in our schools!”

This provocative anecdote shared by Shirley Miske illustrates a disconnect between policy and practice in gender-inclusive education. It is clear that policymakers have a lot to learn about the gender-based challenges that exist in their local classrooms before we can truly achieve gender equality in education. But, how do we get there—to a world where teachers are supported, both in training and with resources, to create gender-inclusive learning spaces for their students? Here, we highlight five key takeaways from the panel discussion that can help chart us on a path to that better world:

1. Teachers are gendered beings: In creating gender-inclusive learning environments, be it in the classroom or in after school clubs, education stakeholders tend to forget that teachers themselves are products of their society and can carry with them the gender norms “baggage” of their communities, for better or for worse. Interventions tend to focus on strategies for changing gender norms and attitudes of students, missing a key opportunity to address the gender biases that teachers—whom the education community has tasked with the responsibility of catalyzing wider gender norms change—may hold themselves. Through supporting teachers to take on reflective practice, through gender-sensitization workshops, for example, teachers can become more aware of and take action on their own biases.

2. Tools abound regarding the how-to: One of the greatest hurdles to supporting teachers to adapt and implement gender-inclusive teaching strategies is the lack of training and information. The good news is that there are tools and resources that have already been developed. For example, IIE developed teacher programming in Ethiopia utilizing interactive learning to focus on the experience of being a girl in the classroom. In addition, IREX has developed Creating Gender Friendly Learning Environments guidebook tools, which provides teachers and educators with practical strategies and resources for developing gender responsive learning environments. Other resources and tools for classrooms and communities include the Forum for African Women Educationalists’ Gender Responsive Pedagogy: A Teacher’s Handbook; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Resource Pack for Gender-Responsive STEM Education; and United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative’s (UNGEI) background paper on the evidence around gender responsive teaching practices.

3. Give girls (and boys) space to voice their experiences and concerns: Panelists also emphasized the urgent need for educators and policymakers to listen to girls and boys. This serves as an important reminder that the student-teacher relationship is vitally important to teachers’ effectiveness in guiding students through critical reflection on their own understandings of gender. Indeed, it is the teacher’s ability to recognize and understand local social and gender dynamics by giving voice to boys’ and girls’ experiences that teachers can create more gender-inclusive learning environments in some of the most gender-exclusive contexts.

4. Align gender indicators with other classroom standards: An important discussion point arose about the challenges in linking program-specific attempts at supporting teachers with policymaker buy-in. This includes getting ministries of education to build in serious financial investment in supporting teachers in the vision to create gender-inclusive learning environments. As a stand-alone goal, some decisionmakers can ignore gender inclusiveness. However, gender inclusive education can gain more attention when it is tied to success in learning standards for all students. Therefore, it is important to come together to develop a set of quantitative and qualitative indicators that places gains in gender equality in the classroom (including gender relations and gender inclusive teaching) equal to academic improvement. The Asian Development Bank and Government of Australia’s Toolkit on Gender Equality Results and Indicators is one place to start.

5. The rising tide lifts all boats: Present lack of political will to provide teachers with the necessary training and long-term support seems to be grounded on the misconception that instituting more gender-responsive and gender-sensitive pedagogies and classroom management techniques means taking attention away from boys. But it is not a zero-sum game. This is particularly important for education stakeholders to grasp, as classrooms are a microcosm of society and a place for reflection and transformation of culture. As the panel discussed, gender-friendly teaching is a powerful foundation for equity in education for all.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How can teachers be more gender inclusive in the classroom?

November 2, 2017