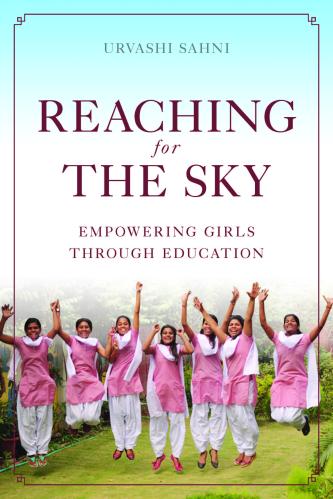

Join us for the launch event for “Reaching for the Sky: Empowering Girls through Education” on September 20 in New York City.

“I used to think – That, so what if I study, I will still just be married off. Because eventually everyone just gets married off. Then here [in school] I learned that marriage is not everything, that I can have a life of my own. I can become anything I want.” — Aarti Singh, Prerna Girls School’s alumna

Girls’ education faces a sense of urgency—globally and in India. The world realizes that many developmental promises cannot be fulfilled unless gender inequality is addressed. Schooling for girls, especially the completion of a high-quality secondary education, is now celebrated by experts as the magic solution to combat many of the most profound challenges to human development, with innumerable social and economic benefits to societies and nations. The argument, however, remains based on efficiency rather than on rights, taking a decidedly instrumental approach and describing the effects of girls’ education on the country’s progress, on economic and social development, on maternal mortality, and on the education of their children.

Most arguments advocating girls’ education see its value in terms of gains for societies, families, and gross domestic product, and its role in training better mothers and therefore better future generations—rather than its intrinsic benefits for girls themselves. It is often not apparent, that there is a concern for a girls’ right to her own life, to a full human existence, and in Aarti’s words, “her right to be able to become anything she wants.” There is a lack of an urgency to view education as a pathway to this goal.

However, there are also clear voices, for example, of Malala Yousufzai, Graça Machel, Julia Gillard, and mine, that state quite firmly that educating girls is important for the simple reason that it is girls’ right to be educated. If it resulted in nothing more than helping them gain control over their lives so that they can live a life of their own choosing, it would still be an immensely important task. Girls’ rights are human rights!

Education, especially for girls living in poverty in countries like India, is an extremely complex undertaking: it requires a multi-perspective approach to be understood and addressed effectively. If we want education to mitigate the harm caused to the girl by nexus of poverty, violence, child labor, early marriage, abuse within and outside families, and lack of care and nutrition, then we need to look closely at the important perspectives of those who are most affected by the issues and problems—i.e., girls themselves, their parents and their teachers. As we get closer to daily lives, we better understand complex concepts of power, hegemony, difference, and equality. Large, complex social problems are played out in this mundaneness of daily life. While the macro perspective provides useful information, locating problems and solutions in larger social and economic structures, showing also the magnitude of the problem, such discussions are inadequate. Girls’ lives and voices get lost when research and arguments center on enrollment, dropout, completion, and achievement rates, even though the discussions are supposedly about them.

It is this gap that I have tried to bridge in my book, Reaching for the Sky: Empowering Girls through Education, where I bring the voices of girls, teachers, and parents, as they tell us about their lives and what they need to make them better. It is only when we understand the social-political realities of their everyday lives that we can design and implement an education that has the potential to “empower” them. My book tells the story of Prerna—our school in India which has focused on girls’ lives and organized its goals, processes, and curricula in response to this.

Many scholars and researchers have questioned the necessary co-relation between women’s empowerment and education. As Plan International’s 2012 State of the World’s Girls report puts clearly, “recent increases in female education have not led to corresponding equality in the workplace or at home. Girls and young women emerge from school still struggling with the idea that they are second class citizens.” It is clear from the arguments of multiple scholars and my experiences with Prerna School that education does not necessarily lead to empowerment or gender equality unless there is focus on process, content, and curricula that critically addresses inequitable social norms and structures.

Laxmi, an alum of Prerna, whose life and whose experiences and opinions of education I have tried to capture in the book, says of her education at Prerna:

“Like in Prerna, they don’t focus on studies first; first they focus on children. Like, where have they come from, who are they, what kind of children are they, so what kind of education should they be given. It’s not just about coming to school, studying and going home… but here along with studying, they ask our problems; they understand.”

Every aspect of education at Prerna—the teachers, the curriculum, the culture of the school, the organization, and the formal and informal structures—is focused on helping the girls construct a sense of themselves as equal persons worthy of being respected by themselves and their communities. It enables them to look critically at the reality of their lives, understand underlying social and political structures, and learn ways of challenging inherent discrimination. It helps them build a capacity to aspire, to take charge of their lives, and to flourish. The school fights to keep them in and to make sure they stay and learn to read, write, and most importantly: recognize themselves as equal persons with a right to determine the course of their own lives. This is seen through the gleaming empowered self of Aarti:

“I think I can face any problem in the future. I can’t stay silent if I feel something is wrong. I want to learn and grow. I can’t stay at home now and do nothing. I want a career, a government job. I am preparing for that. … Like teachers used to say—girls should have an identity of their own. So I have learned to think like that about myself.”

Thus, girls must not only come to school, stay, and graduate. Their education should empower them with the essential knowledge that they have the right to use this education for their own purposes, that they are equal persons with choice, agency, aspirations, and a voice that speaks up against discriminatory practices and social structures.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Reframing girls’ education in India

September 13, 2017