Executive summary

Real estate markets have complex interactions with climate change. Homes, offices, stores, and other buildings are major contributors to greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs), the cause of global warming. At the same time, buildings—and the people inside them—are highly vulnerable to physical damage from floods, wildfires, and high winds. Buildings in high-risk locations also face financial harms, such as rising insurance premiums and a potential decline in property values. Therefore, a green transition will require investments aimed at improving buildings’ sustainability (reducing GHG emissions) and resilience (making buildings safer). In the U.S., most of these investments will require retrofits of existing structures; new constructions adhere to more recent building codes, but they constitute a very small share of the overall building stock.

This leads to an obvious question: Who will pay for these climate investments? Roughly two-thirds of U.S. households are homeowners; how many of them have the financial resources and technical expertise to undertake appropriate energy-efficiency and resilience upgrades? Many low-income households rent their homes, so they are dependent on their landlords’ actions. Owners of commercial properties—including apartments, offices, stores, factories, and warehouses—range from small mom-and-pop landlords to real estate investment trusts (REITs) to sovereign wealth funds. Different types of property owners have widely varying access to financing sources and costs of capital—not to mention the organizational capacity to research the right type of climate investments, obtain equipment, and oversee contractors.

This report provides an overview of the challenges facing private-sector real estate markets as they adjust to climate change, focusing particularly on sources of funding that can support green investments in buildings. The analysis synthesizes insights from academic research, drawing particularly on recent empirical work in urban and real estate economics. The report does not address climate investments in real estate owned by government agencies or large institutional nonprofit organizations, such as universities and hospitals.

Key findings from the report include:

- The breadth and complexity of the industry means that climate investments are likely to emerge unevenly, particularly under the patchwork of current policies at the local, state, and federal levels. The four primary challenges to privately led climate investment are: highly decentralized ownership and decisionmaking, property owners and managers facing a lack of relevant information, fragmented funding sources, and inconsistent policies from public agencies.

- The prospects for climate investments in both owner-occupied homes and commercial properties depend heavily on the resources of property owners—raising serious concerns about equity. Affluent homeowners can upgrade their properties by tapping into their savings or borrowing against accumulated home equity—options that would be difficult for homeowners with tight budget constraints. Rental housing raises even greater concerns because renters have lower average incomes than homeowners; moreover, low- and moderate-income renters tend to live in older, poorer-quality buildings that are less likely to meet stricter building codes or energy-performance standards. On the resilience side, low-income households and communities (as well as commercial properties) often face greater physical risks yet have fewer financial resources to protect themselves.

Climate stresses on homes and commercial real estate will only increase in the coming decades. Better communication between public agencies and private real estate actors about climate investments, as well as deliberate attention to equity concerns, will be necessary to increase the sustainability and resilience of buildings and communities.

Introduction

The economic, social, and human costs of climate change are becoming increasingly salient across the U.S. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) to slow the pace of climate change will require behavioral changes from households, businesses, civic organizations, and public agencies. Additionally, communities are struggling to protect themselves from increasingly intense—and sometimes unexpected—climate events ranging from wildfires and intense storms to extreme heat and drought.

While all sectors of the economy will need to engage in adaptation and mitigation efforts, the real estate sector faces particular stresses. Homes, offices, stores, and warehouses are substantial contributors to GHG emissions, and these buildings are vulnerable to damage from climate events. Most real estate in the U.S. is owned by private individuals or companies, who bear the primary responsibility for maintaining and upgrading their properties. How quickly a green transition in the real estate sector happens will depend on the knowledge, resources, and decisions of millions of individual property owners.

The goal of this report is to provide an overview of the challenges facing private-sector real estate markets as they adjust to climate change, focusing particularly on sources of funding that can support green investments in buildings. By synthesizing insights from academic research, we identify four primary challenges to more widespread adoption of climate investments: highly decentralized ownership and decisionmaking, property owners and managers facing a lack of relevant information, fragmented funding sources, and inconsistent policies from public agencies. Further, climate investments depend heavily on the knowledge and financial resources of property owners, raising serious concerns about equity issues in undertaking these investments.

Buildings contribute to environmental damage and are vulnerable to climate events

Buildings are a substantial contributor to GHG emissions and are highly vulnerable to physical and financial risk from climate events; therefore, a green transition will require investments aimed at both mitigation and adaptation. Furthermore, the real estate sector is exposed to considerable transition risk, as local, state, and federal government officials adopt new policies and private capital markets reconsider where to channel resources.

What kinds of investments could make buildings more sustainable and resilient?

The building sector contributes to GHG emissions directly through energy consumption and indirectly based on where homes, offices, and stores are built. Buildings consume energy for heating, cooling, hot water, and the operating of appliances. Residential and commercial buildings together account for roughly 30% of GHG emissions (including indirect emissions from electricity generation). Additionally, where buildings are located relative to economic activity, infrastructure, and amenities impacts GHG emissions from the transportation sector. Low-density residential and commercial development creates greater distances between homes, jobs, and retail and services locations, and low-density development is difficult to serve efficiently through public transportation. Better land use planning could allow people to commute to work and run errands by using public transit, walking, or cycling. The production of building materials—especially concrete and steel—also causes GHG emissions (as discussed in a related report).

On the mitigation side, a variety of physical investments are needed to decarbonize buildings, as summarized in Table 1 below. Replacing heating systems that rely on natural gas or home heating oil with electric heat pumps, which both heat and cool buildings, is a major focus of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. Replacing old, leaky windows and doors with new, double-paned, tight-fitting windows and doors—and adding insulation and sealing air leaks—can reduce energy usage from heating and cooling systems. New appliances, such as hot water heaters, dishwashers, and clothes dryers, are more energy efficient than appliances from several decades ago. About half of U.S. homes are over 40 years old; retrofitting older homes and commercial buildings is one of the major challenges for decarbonizing buildings.

As for adaptation investments, buildings across the U.S. face high physical risk from several types of climate events, including floods, wildfires, and high winds. Extreme temperatures can also damage buildings, particularly when they occur in regions of the country that are unaccustomed to extreme heat or cold. For example, below-freezing temperatures in the Deep South are more likely to lead to water pipes bursting.

A range of adaptation strategies could help protect buildings and their occupants from climate risks. Elevating structures in flood-prone areas, using fire-resistant exterior building materials, bolting roofs more securely against high winds, and coating external surfaces with heat-reflective ultrawhite paint are all ways that individual property owners can reduce the expected harms of climate events. Some of the most effective adaptation strategies require community-level investments, such as upgrading stormwater management systems and installing rain gardens to handle higher volumes of rainfall or increasing the tree canopy to cool entire neighborhoods.

The cost of mitigation and adaptation investments can vary widely, making it difficult to estimate the scale of funding needed. What types of retrofitting investments are needed depends on the age, structure type, size, and quality of existing buildings. In addition, construction sector wages and benefits vary widely across regions of the country—as does even the availability of contractors with relevant expertise. Community-based investments require implementation from local or regional governments and potentially support from civic organizations. As later sections will discuss, varying expertise and access to financing by property owners is one of the major hurdles to an equitable transition of the buildings sector.

Real estate values and operating costs are likely to change in response to climate events and policy changes

Physical climate risk creates direct financial risk to property owners through several channels. A growing body of research shows that owner-occupied homes that face higher risks of flooding and wildfires sell for lower prices than similar homes in the same city, and research also indicates that sales volumes for high-risk homes also decline after disasters. These papers find that impacts mostly follow in the short term after high-visibility events, but they often disappear within 3–5 years. Commercial real estate (CRE) prices also decline after flooding from intense storms. There is less consensus on whether climate risks impact rents for apartments; fewer studies have looked at residential rental markets, partly because of the difficulty in observing rent data for small geographic areas. Another notable gap in the research is the impact on real estate markets of chronic stresses, such as extreme heat and drought.

Both acute and chronic climate stresses can also increase operating expenses for both owner-occupied and investor-owned real estate. Most notably, the past several years have seen rising insurance premiums and declining availability of policies in states such as California, Florida, and Colorado. Both households and businesses often experience disruptions in their income following natural disasters, which can increase the probability of delayed or missed rental and mortgage payments, especially among low- and moderate-income households. Climate change is also likely to impact expenditures on property maintenance, utilities, local property taxes, and user fees; further research is needed on these topics.

While all sectors of the economy face climate risk, the physical, place-based nature of real estate makes it one of the higher-risk sectors. Uncertainty over regulatory changes to mortgage markets and financial institutions also creates substantial transition risk. One channel through which the housing finance system could discourage development in climate-risky areas would be for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to price location-specific risks into the cost of conforming mortgages through higher interest rates or lower loan-to-value ratios. Government-sponsored entities (GSEs) are not currently allowed to incorporate climate risk into pricing; allowing them to do so would require Congressional authorization—by no means an easy political lift. In the CRE sector, expectations of higher variance in future rental payments in risky locations may impact the cost and availability of debt and equity.

More generally, the increasing partisan divide on climate policies at the federal level—which results in large-scale policy changes across administrations—makes it difficult for regulatory agencies and private firms to set consistent medium- and long-term strategies. Understanding the impact of policy volatility on climate investments is a critical topic for future research.

Changes in insurance markets, including state regulation of insurers, is another area of substantial concern. Both the underlying market dynamics and the academic research on this complex topic are evolving rapidly; this report does not try to comprehensively summarize the literature. Property insurance markets are regulated by state governments, which have typically intervened to maintain affordability to households and small businesses—even if such interventions result in losses to insurance firms. Households’ willingness to pay for insurance—especially extra coverage for floods, earthquakes, and other natural disasters—is lower than the actuarially fair price to insurers. In the past several years, traditional insurance companies have scaled back their business—not writing policies for new customers, not renewing policies for existing customers, or exiting certain markets altogether—in states with high climate risk, including California, Florida, Iowa, and Louisiana. The resulting gaps in insurance markets are being partially filled by new, lower-quality firms and state-run plans (typically intended as insurers of last resort). In this quickly evolving market, policymakers and financial institutions would benefit from greater transparency on insurance pricing, coverage gaps, insurer capitalization, and the fiscal sustainability of public insurance plans. Understanding the interactions between insurance markets and mortgage markets is also important: to what extent do gaps in insurance coverage increase mortgage delinquencies and defaults?

On the mitigation side, policy changes and shifts in private capital markets add to the transition risk. Some local and state governments are already adopting more stringent requirements for buildings’ energy performance. New York City’s Climate Mobilization Act requires roughly 50,000 older buildings to upgrade their energy performance starting in 2024, with the goal of reducing emissions 40% by 2030 and 100% by 2050 at an estimated cost of $20 billion. According to a survey from the National Association of Home Builders, Energy Star windows and appliances are among the most important features that buyers want in newly built homes. Moreover, private sector investors are willing to pay a premium for green buildings in the CRE market. It is unclear what will happen to older, less efficient buildings; in many cases, retrofitting them costs more than demolishing and rebuilding.

Homes and commercial properties face different financing ecosystems for climate investments

The U.S. real estate market consists of three main segments: owner-occupied homes, commercial properties, and public or institutionally owned properties. Climate investments for these segments face different challenges because the availability of financing, units of decisionmaking, and regulatory environments differ across the three segments. Importantly, the financial incentives for undertaking climate investments also vary by segment, which implies that different policy levers may be needed to encourage resilience and sustainability actions.

Owner-occupied residential properties

About two-thirds of homes in the U.S are owned by the people who live in them. Most of these are single-family homes, with a smaller share of condominiums or cooperatives in multifamily buildings. Most owner-occupied homes are built by private, for-profit developers as part of larger residential subdivisions. Newly built housing constitutes about 1 percent of the total housing stock in any given year. Developers decide the location of new housing growth, conditional on land use regulations set by local governments. The structural characteristics of new homes, which are important for energy efficiency and resilience to climate stresses, are also determined by developers and home builders, subject to building codes adopted and enforced by state and local governments. Outside of new construction, individual homeowners make decisions about operations, maintenance, and upgrades to their homes, all of which influence resilience and sustainability.

Sustainability investments in owner-occupied homes offer the clearest alignment of financial incentives: homeowners pay the upfront cost of energy-efficient investments and then receive the benefits of lower utility bills. Several of the recommended Energy Star upgrades—notably equipment for heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) and water heaters—have usable lifespans around 10–15 years, creating natural opportunities for homeowners to make climate-friendly choices. Tax credits and other pricing nudges can further ensure that homeowners can recoup the costs of sustainability investments within a designated time period.

The financial incentives for homeowners to undertake resilience investments (ones that do not also serve a sustainability function) are less clear. For homeowners in especially risky locations, some types of upgrades (elevating properties in flood zones or installing fire-resistant roofs) may be required by insurance companies for the property to retain coverage. However, these investments may not result in lower insurance premiums to help offset costs. It is much more difficult to quantify the expected savings from resilience investments (reflected in, for instance, lower probability of damage, lower value of damage, and greater preservation of resale value), in part because of the inherent uncertainty of climate events. Better cost-benefit analysis of resilience investments would help guide both property owners and policymakers.

Commercial properties

The commercial property segment consists of rental housing (both single-family and multifamily structures), office buildings, retail locations, and industrial properties. Unlike owner-occupied housing, most commercial properties are owned, operated, and occupied by separate entities. For example, it is common for office buildings to be owned by large institutional investors, operated by professional property management firms, and occupied by multiple companies or organizations, each of which has a separate lease that governs the terms of use for each tenant’s portion of the building. This implies that decisions about climate investments for a given property may reflect the preferences of multiple different entities, as well as building codes or other regulations set by government agencies. Industrial properties—such as factories and warehouses—are more likely than office or retail buildings to be owned by the companies that occupy them.

A key factor in decisions about climate investments is the capacity of property owners, roughly defined as staff expertise and access to financial resources. Large, high-value properties are generally owned by large institutional investors, such as REITs, pension funds, insurance companies, private equity firms, and other specialized real estate companies. However, many commercial properties (including small apartment buildings) are owned by small-to-midsize companies, families, and individuals, often referred to as mom-and-pop landlords. The financing sources available to large institutional owners and mom-and-pop landlords are quite different.

The financial incentives for owners of commercial properties to undertake either sustainability or resilience investments are more complicated than the incentives for homeowners. Depending on lease structure, utility bills may be paid either by property owners or tenants, which makes it harder for landlords to fully capture cost savings from energy-efficient upgrades. Some tenants may be willing to pay higher rents to occupy space in sustainable or resilient buildings, which could encourage upgrades, especially if landlords can retrofit parts of buildings as leases turn over. Designing policy nudges for the CRE sector is likely to be more difficult, given the fragmentation of decisionmaking in the sector.

Public and institutional properties

The third real estate segment consists of properties owned by public agencies (such as federal, state, local, or special purpose governments) and large nonprofit organizations, such as universities, religious organizations, and hospitals or medical systems. Decisionmaking systems, motives, and access to capital in this segment differ from those of either owner-occupied residential properties or for-profit CRE properties. Public agencies own a relatively small share of properties used for general-purpose office space, retail locations, or housing (unlike some countries where publicly owned housing constitutes a large share of the overall housing stock). Public ownership is more common among specialized buildings used for public purposes, such as schools, libraries, dormitories, health care facilities, train stations, and airports. Within some local markets, universities and religious organizations may be relatively large landowners; for instance, Columbia University and New York University have large real estate portfolios in Manhattan, as do the local Catholic and Episcopal dioceses.

There are several important reasons why public and nonprofit agencies may approach climate investments differently than private, for-profit companies (of any size) or individual households do. First, governments and nonprofits often plan for longer time horizons, implying that they have a lower discount rate for net present value calculations. Second, they have access to different funding sources (such as direct tax revenues or municipal bonds for government entities), and they receive different tax treatment than households or businesses; federal and local tax policies are important factors in many real estate decisions. Municipal bond markets have begun factoring climate risk into the availability and cost of long-term lending; communities that face higher physical risk may face higher borrowing costs.

Because this report focuses on private-led climate investment, the remainder of the report will primarily discuss investments in the owner-occupied housing and commercial property segments.

Real estate finance encompasses a wide range of financial institutions and instruments

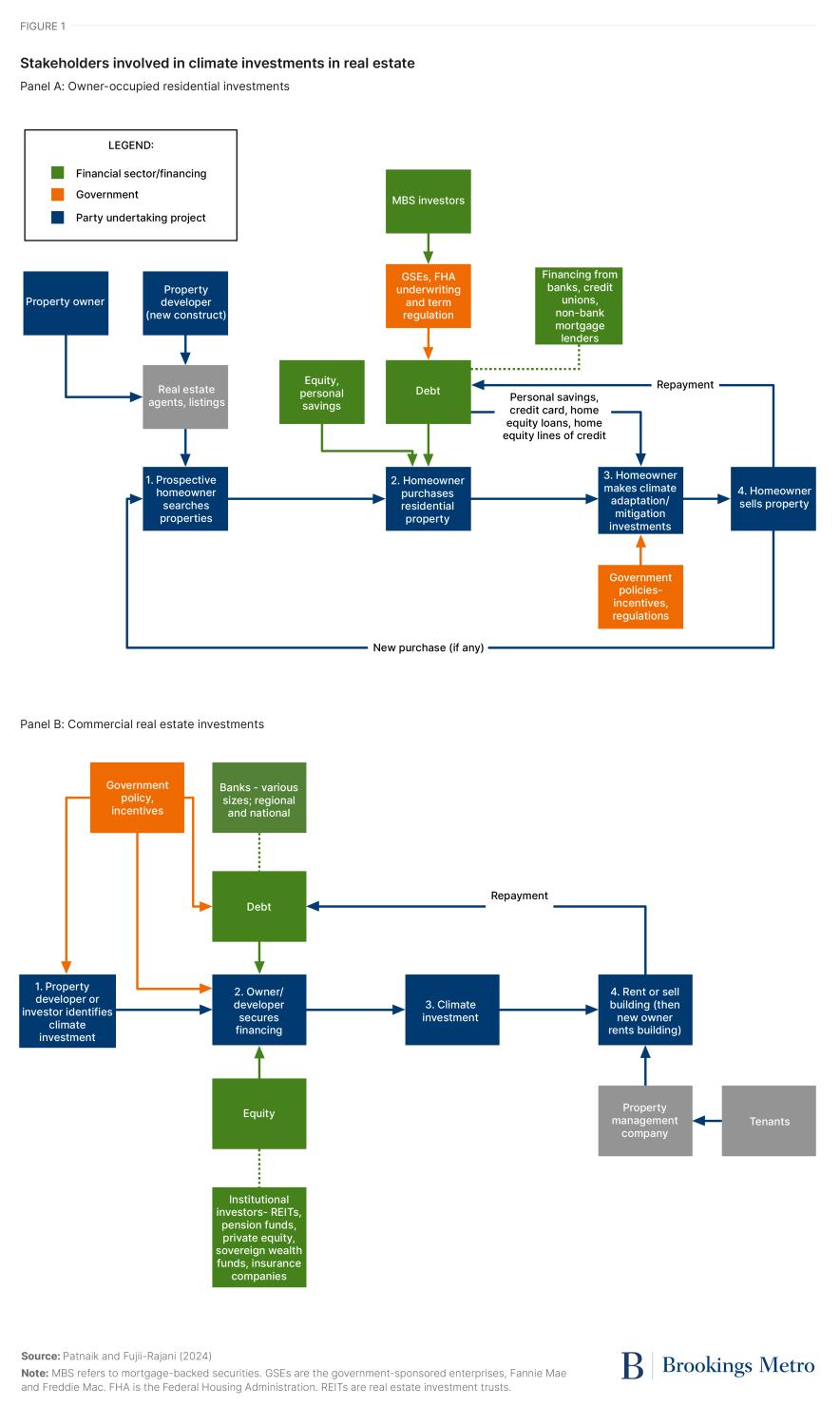

Real estate finance is a large and diverse sector composed of a wide range of funding sources and financial instruments. Financing structures vary across markets segments and activity types, including development and construction, acquisition of existing properties, rehab or upgrading of existing properties, and refinancing. The dual diagrams of Figure 1 display the set of stakeholders involved with climate investments in owner-occupied residential and commercial properties.

Owner-occupied residential properties

The set of financial institutions and instruments that provide capital for purchases of existing owner-occupied properties are the most regulated part of real estate finance—and, not coincidentally, the market segment on which the best data are available. Homebuyers can obtain purchase loans and refinance loans from a wide range of banks, savings associations, credit unions, and nondepository mortgage companies. The share of nonbank lenders has risen over time; today they account for about half of all mortgages. The typical U.S. homebuyer pays 5–20 percent of the purchase price up front, using their savings. The remainder is financed as a 30-year fully amortizing fixed-rate loan. The federal government regulates mortgage terms and underwriting criteria, both to protect consumers and to ensure safety and soundness of lending institutions. Most loans are securitized after origination by the GSEs, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, or by their smaller public counterpart, Ginnie Mae (for Federal Housing Administration (FHA), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) loan products). The single-family lending space covers residential properties with between one and four units per property; larger multifamily buildings fall into the CRE category. Data on loan terms and some borrower characteristics are compiled in a publicly available database, as required by the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act.

Because federally regulated entities dominate the home purchase mortgage market, changing federal policies could have substantial impacts on the incentives for climate investments. But currently the GSEs’ and FHA’s underwriting processes do not consider property- or location-specific climate risks or climate impacts (in terms of, for instance, energy-efficiency, water usage, or proximity to transit). In the early 2000s, Fannie Mae experimented with a small pilot program for location-efficient mortgages, offering reduced mortgage pricing for homes near transit. Freddie Mac offers some incentives for energy-efficient homes. Such programs could conceivably serve two goals: encouraging homeowners to take climate-friendly actions and reducing household expenses on utilities and/or car usage. (The latter goal could justify favorable mortgage pricing if lower expenses reduce default risk.) While these pilot programs have been quite small and/or short-lived to date, pilots offer an opportunity to test product design and market demand before programs are scaled up.

How homeowners can obtain financing to undertake renovations and retrofits of their current homes is particularly important for the ease of climate investments. For non-climate-related home improvement projects, households typically pay through some combination of personal savings, credit card debt paid down over time, and home equity loans (HEL) or home equity lines of credit (HELOC). Obtaining a HEL or HELOC requires households to have strong credit ratings and substantial amounts of equity or other financial assets. This implies that affluent households will have an easier time financing and undertaking climate investments; lower-income households are more likely to rent their homes, and low-income homeowners often struggle to afford basic health-and-safety-related maintenance.

Financing for new construction of owner-occupied homes is another potential mechanism to influence climate readiness. Financing sources for the development of larger residential subdivisions (usually single-family detached homes or townhomes) or multifamily condominium buildings are more like the CRE market, discussed below. Private-sector developers can obtain development and construction loans from commercial banks, along with equity assembled from their own resources and outside investors.

Commercial real estate

The CRE finance market is wildly heterogeneous and highly opaque to most outside observers. Commercial property owners run the gamut from individuals who own small standalone shops to multinational firms with complex portfolios of trophy properties, as well as sovereign wealth funds from around the world. One important source of capital is traditional banks, given that CRE makes up a substantial part of the portfolios for many local and regional banks, as well as large investment banks. Other important sources include institutional investors such as REITs, pension funds, and private equity as well as insurance companies. CRE lending consists of several main segments: land acquisition, land development, and construction (referred to collectively as ADC), as well purchases and refinancing for existing income-producing buildings.

Typically, purchases of commercial properties involve both debt and equity and may include many separate partners or entities. Commercial mortgages are much less standard than residential loans, and terms can vary widely, depending on negotiations between borrowers and lenders. Some CRE loans are held in portfolio by the originating lenders, while others are securitized into commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) and sold to investors. Large companies can finance projects by issuing corporate debt, bypassing lending institutions. Equity arrangements are even more varied and complex; because of the large sums involved, large CRE deals can have multiple layers of equity partners who receive different prioritization over operating cash flows and/or property appreciation. Because CRE finance operates mostly as private contracts, very little information is publicly available.

CRE lending operates under a very different regulatory regime than owner-occupied housing, in large part because it has less direct impact on consumers (households). Researchers in the Federal Reserve System have analyzed CRE loans held in portfolio by large banks, as part of banks’ capital assessments and stress tests. The GSEs have a nontrivial role in acquisition lending for multifamily properties.

As with the owner-occupied sector, the diversity of CRE property owners—and varying access to capital—raises questions about the pace of climate investments and equity impacts related to policy changes (such as, for instance, requirements for buildings’ energy performance). Large corporate owners will be more able to access capital (or do so on more favorable terms) to undertake retrofits than small mom-and-pop landlords. Some local programs exist to help small, credit-constrained landlords undertake upfront investments that could pay for themselves in reduced energy costs over time.

Public and institutional properties

Public sector agencies that own real estate can finance acquisition, development, or renovations through direct revenues (such as dedicated funding appropriated by local, state, or federal legislatures) or by issuing tax-exempt bonds (for entities with independent credit authority). This report focuses on private-led climate investments, excluding publicly financed building construction and retrofits. Information on financing sources and climate investments among large nonprofit entities—including universities, medical institutions, and religious organizations—is outside the scope of this report (and virtually impossible to find data on).

Climate investments in real estate markets have the potential to exacerbate equity concerns

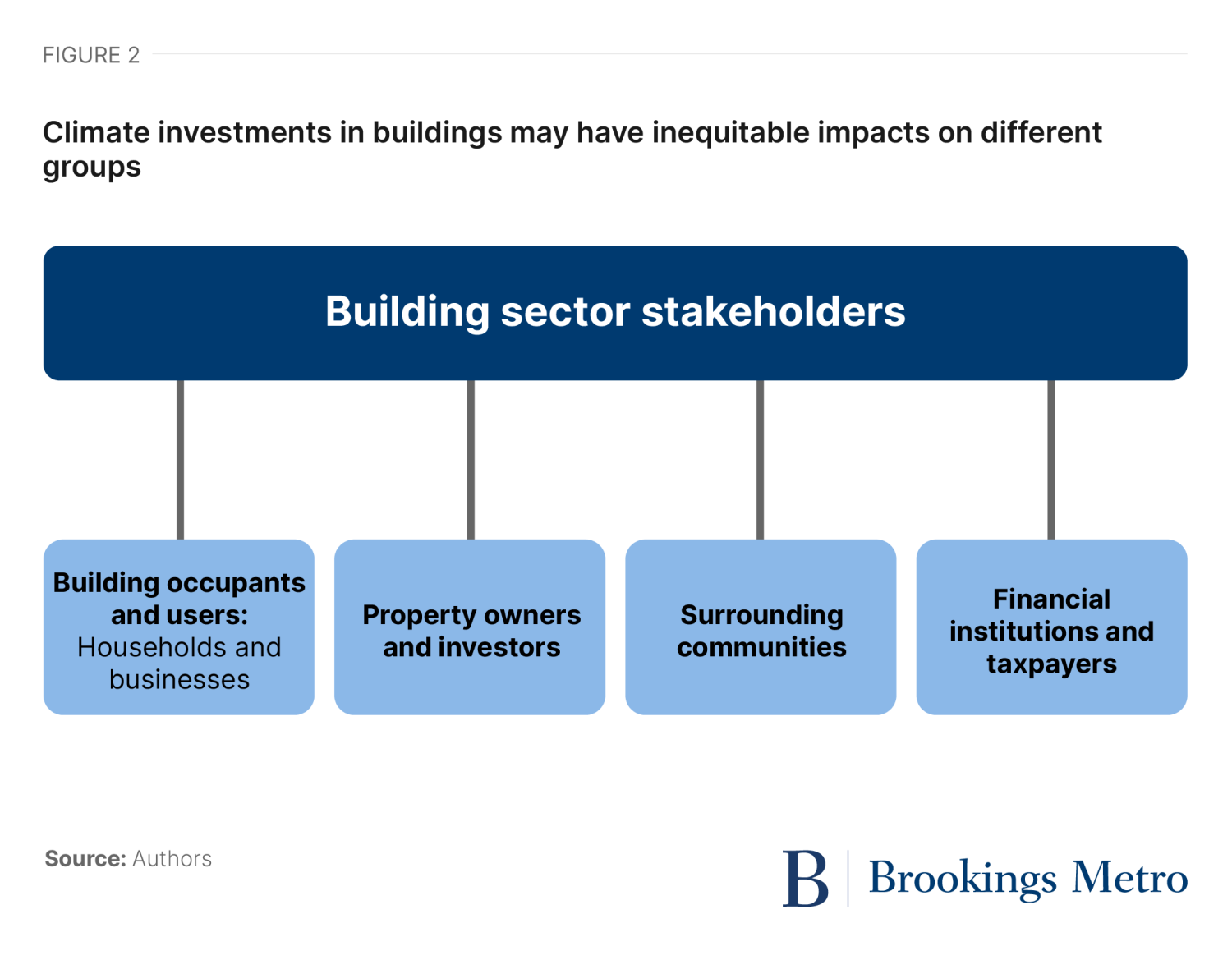

In considering the equity implications arising from climate investments in the buildings sector, the impacted people and entities can be organized into four groups, as shown in Figure 2 below.

- Building occupants and users: This includes households for owner-occupied and renter-occupied homes, as well as businesses and customers who use office, retail, and industrial properties. Resilience investments should reduce the physical risks to building occupants. Sustainability strategies can reduce financial risks or costs to building users (such as utilities and property insurance), and these strategies can encourage behavior that impacts emissions (such as water and energy usage).

- Property owners and investors: The clearest equity concerns are that climate risks and/or policy changes could harm the value of owner-occupied homes, which are the largest financial asset for middle-income households. Mom-and-pop landlords of smaller commercial properties are also at risk for reduced incomes.

- Surrounding communities: Unsafe buildings increase risk of physical harm for neighbors. Poorly maintained buildings, or those with declining property values, can create negative spillover effects for nearby communities. Declining property values also imply lower revenues for local governments—which are on the front lines of disaster planning and recovery, including the rebuilding of local infrastructure.

- The upstream financial system and taxpayers: Disruptions to rental income and declining property values pose systemic risks to banks and other mortgage lenders, CRE investors, and insurance companies. U.S. taxpayers are ultimately responsible for losses from mortgages securitized by the GSEs and public insurance or disaster recovery programs.

The diverse range of property owners raises concerns about who can afford to undertake adaptation and decarbonization investments if they are mandated by regulators but not subsidized. In the case of most property retrofits, it is assumed that property owners will assume upfront costs, which may be recouped over time through lower operating costs, lower insurance premiums, or increased value upon the sale of the property. But many homeowners and small CRE owners face binding credit constraints and have limited savings to pay out-of-pocket for these costs. The residential rental sector is a particular concern because (a) renters have lower average incomes than homeowners, (b) low- and moderate-income renters tend to live in older, poorer-quality buildings that are less likely to meet stricter building codes and energy performance standards, and (c) owners of lower-rent buildings operate on tight margins and are less able to access financing for retrofits.

Financial constraints will be particularly acute following natural disasters, when many properties often need to be repaired or rebuilt. Rebuilding offers an opportunity to make structures more resilient and sustainable, but property owners may have experienced income disruptions due to such disasters, and lenders may be reluctant to finance rebuilding in the same location. Increased vacancy rates or turnover in rental properties may make it more difficult for landlords to obtain loans.

As higher climate risks translate into lower property values, higher-risk communities (neighborhoods or cities) will face cascading financial impacts. They will have more difficulty accessing insurance (or will pay higher insurance premiums), and lower property values will make it harder to access credit (such as HELOCs) to finance resilience investments. Climate-risky communities today vary widely in initial income and wealth, ranging from flood-prone, low-income, Black and Latino neighborhoods in cities like Houston and New Orleans to affluent coastal areas in Florida and California with expensive vacation and second homes.

Equity considerations are not systematically incorporated into real estate financing decisions, either for the general financing of development, acquisition, and renovation or for the financing of climate-specific investments. The CRE segment is dominated by financial institutions, private-sector developers, and property owners who have few (if any) incentives to consider the equity impacts of their decisions. Financial regulation of this segment is primarily concerned with the safety and soundness of banks, not the impact on households or communities.

In theory, the GSEs and state insurance regulators provide some consumer protections by pooling risks across larger markets (by making it so, for instance, homeowners in risky locations can purchase mortgages and insurance at discounted prices because they are subsidized by households in lower-risk locations). To the extent that high-risk communities are socially or economically vulnerable, this risk sharing reduces equity concerns—but such risk sharing may exacerbate such concerns as well. Risk pooling through mortgage and insurance markets also reduces the incentives for any individual property owner to change their behavior.

Adaptation and disaster recovery programs often use cost-benefit analysis to determine payouts and investments in physical protection. For example, the expected costs of building seawalls or dams are compared to the aggregate value of property to be protected from floods. This approach inherently biases projects towards areas with more expensive real estate.

Case study: Enterprise Resilience Academies

The challenge

It is a stiff challenge to retrofit apartment buildings that serve low-income renters to provide more resilient, energy-efficient homes. This housing segment is characterized by highly fragmented ownership, making it difficult to provide guidance on resilience strategies at scale. Low-income rental buildings are often older, in poor physical condition, and have urgent needs for energy efficiency and resilience retrofits. These buildings house some of the nation’s most vulnerable households: people with low incomes and almost no savings—including families with children, older adults, and people with disabilities—who have extremely limited housing options. The properties operate on narrow financial margins. Unlike owners of market-rate apartments, owners of subsidized housing face programmatic limits on raising rents, which also makes it difficult for lenders to underwrite loans for major upgrades. Some public subsidies and philanthropic funds exist to cover capital improvements, including green retrofits, but these funds are not always easy to find or access.

What Resilience Academies do

In 2021, Enterprise Community Partners, a national nonprofit organization, launched a series of Resilience Academies to help affordable housing owners, property managers, and developers learn about strategies to increase the climate resilience of low-income housing. Each Resilience Academy brings together a regionally based cohort of affordable housing providers—nonprofit organizations, public agencies, and for-profit firms—for several weeks of in-person training sessions. The curriculum covers a range of topics, including:

- assessing portfolio risk

- ensuring continuity of operations during and after natural disasters

- building new and resilient homes

- retrofitting existing homes

- understanding local laws and regulations

- engaging local communities

- and finding necessary funding and financing

The geographic grouping allows the training sessions to focus on climate risks that are similar across each cohort. For instance, hurricanes are a primary concern to organizations across the Southeast and Gulf Coast academies, while wildfires are a chief concern among Rocky Mountain participants. Sessions include presentations from subject-matter experts, supplemented by an extensive set of written training materials. The in-person gatherings also support peer-to-peer learning and networking among similar organizations.

Outcomes

Between 2021 and 2023, Enterprise Community Partners completed five regional Resilience Academies covering the Southeast, Gulf Coast, New York, New Jersey, and Rocky Mountain regions, respectively—and over 150 participating organizations attended them. To better understand the outcomes and effectiveness of the Resilience Academies, Enterprise Community Partners has contracted MEF Associates and the Institute for Sustainable Communities to conduct an evaluation.

Looking ahead

The Resilience Academies are a promising approach aimed at overcoming the dis-economies of scale that result from fragmented property ownership in the affordable housing market. The small-cohort model creates more efficient training methods than trying to do one-on-one outreach to individual property owners, while also creating the opportunity for peer-to-peer learning. On the other hand, keeping each regional academy small enough to allow in-depth learning implies that Enterprise Community Partners will need to conduct many separate academies to reach a substantial share of affordable housing providers. In-person trainings are necessarily resource intensive (especially given the need for subject matter experts to teach). The supplemental materials, including online videos and written training guides, are publicly accessible and offer another channel to increase the scale and reach of the program.

Three major pain points hinder equitable outcomes of climate investments in real estate

Decentralized and heterogeneous ownership distribution

It is very hard to get information out to the millions of homeowners and thousands of commercial property owners responsible for making decisions about climate investments. Property owners have wildly unequal resources to undertake and finance investments related to mitigation and adaptation. The availability of contractors with expertise in climate-friendly building techniques varies considerably across local markets.

Split levels of policy and regulation

The federal government regulates mortgage markets for owner-occupied residential properties. State governments oversee property insurance for residential property and CRE. Local governments regulate land use, construction, and building performance and safety. Financing for CRE is regulated by federal and state banking regulators for safety and soundness. The largest CRE owners and investors—including REITs, private equity firms, and sovereign wealth funds—do not fall under the jurisdiction of banking regulators.

Political sensitivity around climate risk–based pricing and limiting development

Federal, state, and local elected officials are wary of allowing, let alone requiring, the prices or availability of mortgages and insurance to reflect variations in climate risk, especially for owner-occupied homes (though somewhat less so for rental housing). Few public officials want to ask households to pay more money or limit where people can live and operate businesses. Few households want to pay higher taxes to subsidize upfront investments. In parts of the country with climate-skeptical elected officials, it’s hard even to talk about the need for change, let alone to create mandates or taxes.

Conclusion

Improving the sustainability and resilience of U.S. real estate markets is an important goal of the green transition. Buildings are a major contributor to GHG emissions, face high exposure to physical risk from a range of climate events, and are unusually vulnerable to financial and transition risk. Because new construction is a relatively small share of the overall building stock, most climate investments for mitigation and adaptation will require retrofits of existing buildings.

The fragmented and diverse ownership patterns of homes, offices, and other buildings create challenges for implementing climate investments at scale and raise concerns about the equity impacts of such investments. Affluent households are much more able to afford to upgrade the energy efficiency and resilience of their primary residences than lower-income households, especially renters, who have limited decisionmaking powers over their homes. Small CRE owners, including small businesses and family-owned real estate firms, also have limited access to upfront funds for climate investments (or property upgrades in general). In areas with high risk, climate events may disrupt rental income and mortgage payments and lead to declining property values.

A lack of coordination among local, state, and federal policymakers hinders the private sector from financing or undertaking climate investments at scale. In particular, uncertainty about the direction of federal climate policy (including subsidies for building retrofits and energy prices) is a major obstacle to the green transition in real estate markets.

Equitable climate finance series

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Funding for this research was provided by HSBC Bank USA, N.A. The program is also grateful to the Metropolitan Council, a network of business, civic, and philanthropic leaders that provides both financial and intellectual support to the program. The views expressed in this report are solely those of its authors and do not represent the views of the donors, their officers, or employees.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).