A more extreme and uncertain climate is leading to tangible harms across the U.S., including stresses on transportation and water systems. While major storms and other acute shocks can lead to sudden and severe destruction, rising heat and other chronic stresses can lead to gradual environmental, economic, and public health challenges. That means greater operational and insurance risks, as well as rising damage, disruptions, and costs to physical infrastructure assets over time. Risks and costs are uneven across the country, with the most severe impacts tending to hit the communities least able to withstand and recover from them.

These climate impacts are raising the urgency for public and private infrastructure leaders to not only mitigate the worst potential future effects of climate change but also adapt to the current reality. Some leaders are adjusting processes, practices, and systems to survive and thrive in the face of actual or expected climate impacts across transportation and water systems. For instance, investing in more durable and flexible physical improvements—such as seawalls, rain gardens, and permeable streets—can better communities withstand, absorb, or recover from such impacts. These upgrades can also reduce risks, save money, and create additional benefits (such as new jobs) for communities. In fact, every $1 invested in disaster preparation beforehand can save $13 in economic and other related costs after the fact.

However, needed investments in climate resilience—the capacity of social, economic, and environmental systems to cope with climate impacts and respond in ways that maintain or improve their function—are not keeping pace with the level of demand. There is a struggle to measure and assess different climate impacts across regions, including the costs endured and the benefits realized from different transportation and water system improvements. There is a struggle to proactively test new designs and technologies, amid prevailing budgetary and project development processes. And there are a variety of struggles to use new funding and financing approaches that can accelerate adaptation, especially in the most vulnerable communities.

This brief summarizes the need to finance adaptation in the U.S., with an eye toward greater climate equity. It highlights findings from the 2021 Brookings report, “A new climate finance framework for investing in urban resilience,” which describes the scope of the financing challenge and opportunity in more depth. This brief first explores the need for greater adaptation, then examines the major financing struggles, and finally discusses the climate equity dimensions. While these issues touch multiple parts of the built environment, the focus here is on transportation and water systems specifically. Throughout, the brief touches on recent policy and market developments since the release of the original report.

Exploring the climate adaptation challenge

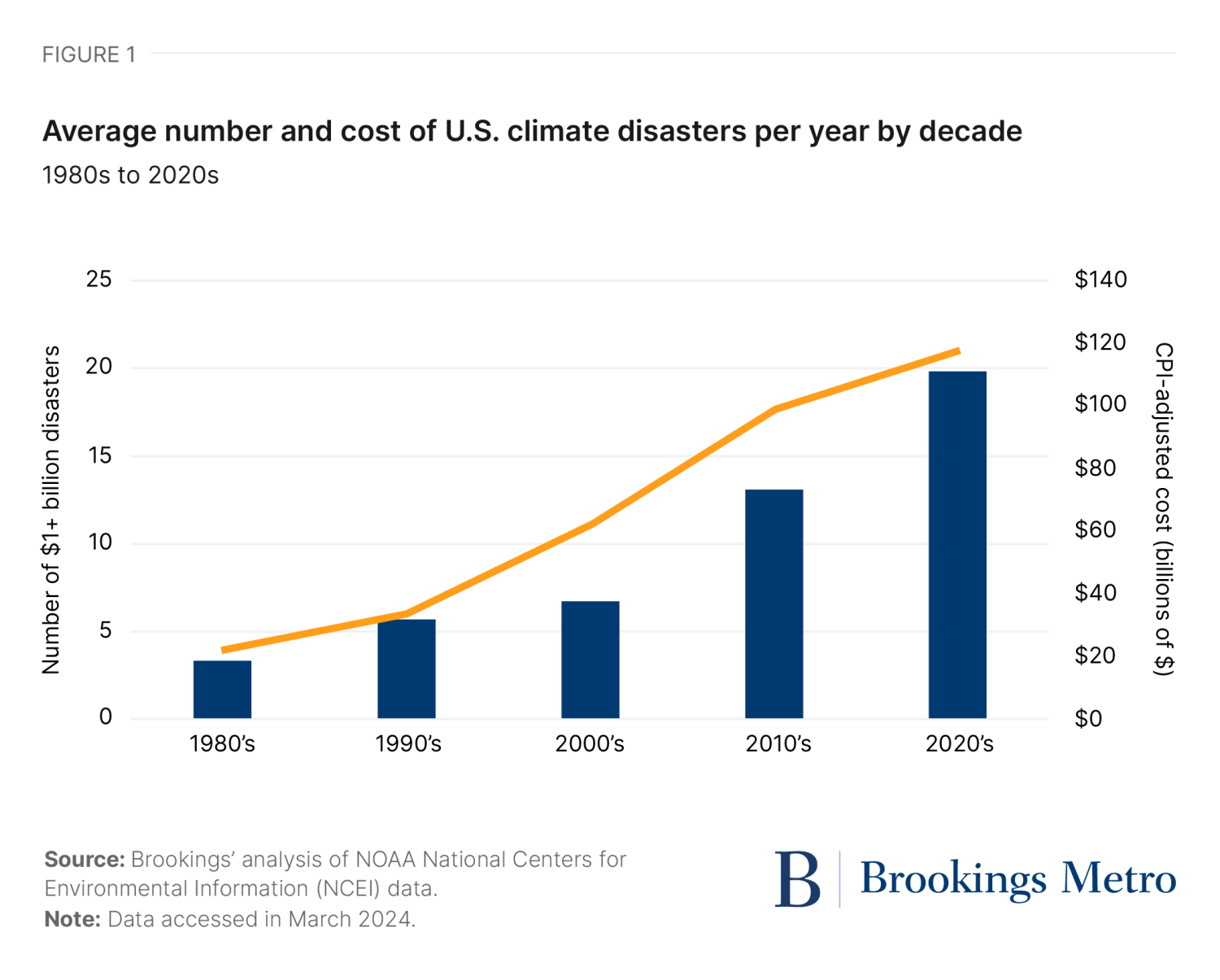

Climate change is causing more frequent and widespread destruction across the country. Floods, fires, and other acute climate impacts are on the rise—and they come with a growing price tag. From 1980 to the time this piece was published, the U.S. has endured 387 climate-related disasters costing at least $1 billion in damage each, amounting to almost $3 trillion total (see Figure 1). These events include not only massive storms and flood events, such as Hurricane Katrina, but also widespread droughts and wildfires. Compared to the 1980s—when there was an average of three such disasters per year, on average costing $21.8 billion annually—the 2010s saw an average of thirteen such disasters per year, costing the U.S. economy $99 billion annually. The 2020s have seen an even higher uptick in such events—an average of 20 disasters per year costing $117 billion. And these costs come on top of more chronic impacts like rising heat waves and droughts that also hurt communities every day.

A foremost concern is protecting against direct impacts of climate-related risks that disproportionately affect some of the country’s most economically and socially vulnerable and exposed communities. For example, Harris County, Texas—the home of Houston—is consistently exposed to billions of dollars in damage from heat waves, hurricanes, and cold snaps. The climate threats in this area are especially pronounced in neighborhoods that have higher levels of social vulnerabilities, like low-quality housing, underlying health conditions, and constrained household budgets that limit local residents’ ability to rebound after a disaster strikes. And the economic ripple effects go far beyond these neighborhoods and Houston as a whole, including supply chain disruptions, slowed or halted production, and more.

Adaptation needs are pronounced across the country’s transportation and water systems. Transportation infrastructure includes roads and bridges; public transit; bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure; passenger and freight rail; airports; inland waterways; and other related facilities that are not only vulnerable to major storms and other acute climate shocks but are also increasingly in need of repairs and upgrades that reduce pollution, improve access, and enhance more sustainable outcomes. Water infrastructure includes drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater facilities as well as rivers, lakes, and other natural systems that face a number of scarcity and pollution concerns. Across both types of infrastructure, aging facilities not only struggle to withstand different climate impacts but may also exacerbate climate-related costs through increased stormwater runoff, urban heat island effects (higher temperatures due to heat radiated by structures such as highways), and other environmental and health challenges.

Challenges with financing climate adaptation

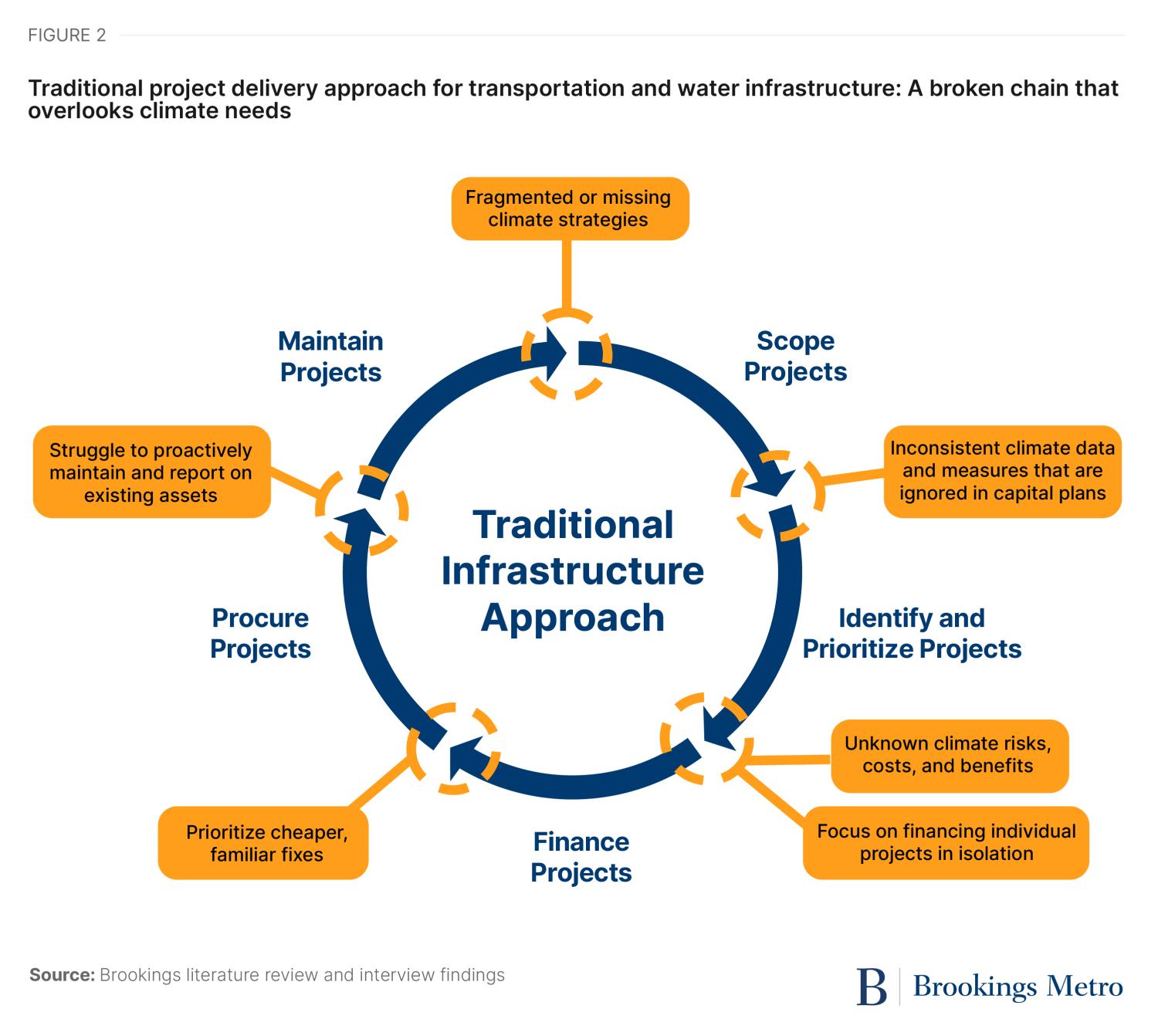

Traditional project delivery for transportation and water infrastructure overlooks many climate adaptation needs—and is typically under the oversight of public owners and operators (such as transportation departments and water utilities). Public leaders involved in transportation and water systems tend to rely on the same types of measurement, planning, and private financing approaches for any infrastructure project, which can be slow, disjointed, and reactive despite the urgency of climate change (see Figure 2).

The 2021 Brookings report provides more details on this disjointed project development process, but the major challenges include: (1) an inconsistent data collection and measurement process based on fragmented or missing climate strategies; (2) a capital planning process to identify current and future infrastructure projects that often overlooks climate needs; (3) a project financing process based on unknown climate risks, costs, and benefits that focuses on individual projects and often prioritizes the same financial instruments; (4) a procurement process that uses the same designs, technologies, and materials that are susceptible to higher risks over time; and (5) an ongoing maintenance process to manage existing infrastructure that often ignores lifecycle costs and reacts to climate needs in real time.

The key takeaway is this: the owners and operators of transportation and water systems—state and local government officials in many cases—struggle to incorporate climate considerations when selecting, financing, and maintaining these kinds of projects. And even if they are trying to address climate needs, they lack the long-term and predictable funding to test new designs, technologies, and planning approaches over time. Although more federal, state, and local leaders are launching new plans and programs to accelerate adaptation—including a new National Climate Resilience Framework released by President Joe Biden’s administration in 2023—these actions are still struggling to unleash widespread investment. Nor is there enough federal funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to allow state and local governments to construct all the necessary improvements at the speed such climate instability demands.

In response, those asset owners are turning to the private sector, which has demonstrated an appetite for driving short- and long-term climate investment. Banks, investment funds, insurers, and other financial institutions are signaling more interest not only in assessing and addressing climate risks but also in shifting more money toward new types of projects. The insurance industry, for instance, is evolving in the types of coverage and products offered to respond to different climate risks, including parametric insurance that covers multiyear, seasonal, or other risks. In addition, municipal bonds represent a common way for transportation and water system owners and operators to construct projects, providing tax-exempt debt to cover a range of projects, including those focused on sustainability and resilience (such as green bonds). While green bond issuances only represent a small segment of the total U.S. municipal bond market—which now stands at more than $4 trillion in outstanding bonds—they are growing in importance, including an estimated 3.5% increase in 2023, compared to a 2.8% drop among all municipal bonds.1

Yet many existing investment models downplay resilience, if they consider it at all. Traditional projects like highways and large stormwater pipes tend to offer more predictable, familiar timelines when it comes to procurement and financing compared to more nascent green infrastructure projects, such as permeable streets or rain gardens. For state and local governments operating with tight budgets and private-sector leaders looking for quick returns on investment, traditional models may suggest adaptation projects do not pencil out in the short term—even though they can offer a range of long-term environmental and economic benefits.

It is little surprise, then, that almost all private climate investment focuses on mitigation (such as emissions-reducing technologies) rather than adaptation. Globally, only about 1.6% of adaptation investment comes from the private sector, even though this market could be worth up to $2 trillion in the coming years. Estimates for the U.S. alone comparing total private investment in mitigation and adaptation are harder to come by, but combined estimates for North America show a similar lag. In 2021 and 2022, $311.2 billion in private investment went toward mitigation projects—or more than 99% of all private climate investment—compared to nearly $2 billion for adaptation projects (see Figures 3 and 4).

Climate equity considerations

The rigid, sequential process that defines transportation and water investment results in similar types of projects and reinforces many ongoing economic and environmental inequities. At each step, this process can overemphasize engineering needs versus community values and can lock in traditional designs and technologies that continue to expose people and places to climate impacts. And while there is heightened private interest in climate investment, that is only the start of making a difference on the ground for more people and places. Public and private leaders are struggling to systematically identify, quantify, and accelerate needed adaptation investments.

First and foremost, there is a lack of consistent measurement—and planning—for resilience at the state, regional, local, and neighborhood levels. In terms of transportation, state and local transportation departments vary in the rigor and scope of planning and measurement around climate equity, including on issues such as access and affordability (in terms of financial risks and exposure) at a household level. In terms of water systems, utilities also vary in the rigor and scope of planning and measurement around climate equity, particularly when it comes to flood and drought risk, including the impacts on individual households. Some cities—such as Austin, Texas, and Detroit—are conducting more extensive “climate equity mapping” efforts to inform these gaps, but there are still questions about how and where this information is used to target future investments. Similar analytical challenges exist in informing the rollout of new IIJA and IRA funding, despite the emergence of federal environmental justice initiatives, such as Justice40. Different normative or partisan attitudes toward climate change across the U.S. also threaten to create inequities between how much different localities and even states invest in climate adaptation.

The lack of coordinated governance across different infrastructure systems, projects, and geographies worsens these climate equity challenges and limits widespread adaptation investment. Even though the climate costs and benefits associated with different adaptation projects often traverse whole regions (connected greenways), transportation departments often operate in isolation from water utilities (and vice versa). Jurisdictional fragmentation can further complicate additional collaboration and investment, including a lack of local fiscal capacity to conduct community outreach or expand workforce development. The varying budgetary capacity, budget timelines, and asset inventories of different entities—including the lagging maintenance and monitoring of specific facility needs—can further expose communities to climate impacts.

Still, improved ways of measuring, reporting, and overseeing climate equity have the potential to better identify the areas of greatest need, protect the areas at greatest risk, and prioritize specific projects that can reduce costs and amplify benefits. Clearer information on climate risks and returns, for instance, can give public entities and private investors more confidence to finance different projects; this has included the emergence of new instruments such as environmental impact bonds (EIBs)—outcomes-based financing tools that provide upfront private capital for environmental projects and then pay investors depending on how the projects perform. Water utilities in cities like Washington, D.C., and Atlanta have already pursued EIBs to support green infrastructure upgrades. Additional adaptation-focused instruments and collaborations, including community-based public-private partnerships, have also shown additional climate investment can go hand-in-hand with additional climate equity.

Conclusion

As climate risks mount across the U.S., the impacts to different transportation and water systems are growing, as are the impacts to the communities that depend on them. In turn, the levels of needed investment are growing, especially for adaptation projects. Reducing costs, amplifying benefits, and ultimately supporting greater climate resilience hinges on more proactive and targeted private financing. Significant information and governance barriers are holding back this financing in many cases, which not only stifles new types of projects but also leaves many communities exposed to ongoing risks. However, improving measurement of these climate impacts and targeting plans in the areas of greatest need can inform adaptation financing and promote more climate equity.

Equitable climate finance series

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Funding for this research was provided by HSBC Bank USA, N.A. The program is also grateful to the Metropolitan Council, a network of business, civic, and philanthropic leaders that provides both financial and intellectual support to the program. The views expressed in this report are solely those of its authors and do not represent the views of the donors, their officers, or employees.

-

Footnotes

- Note: This includes both green and social bonds, according to S&P Global Ratings’ definitions. In particular, for additional details about U.S. municipal green, social, sustainability, and sustainability-linked bonds see Andrew Bredeson, Jessica Pabst, and Bryan Popoola, “U.S. Muni Sustainable Bonds: Moderate Growth In 2024” S&P Global Ratings, February 15, 2024, https://www.spglobal.com/_assets/documents/ratings/research/101593184.pdf.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).