Executive summary

The American transportation sector is dragging down the country’s overall environmental record. Since 2017, transportation activities have emitted the most greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of any economic sector, while the ambient particulate matter emitted from tires, brakes, and tailpipes further degrade local air, soil, and water quality. The only way to reduce these negative effects is to lessen the country’s dependence on fossil fuels and promote cleaner transportation activities.

Private finance is necessary to achieve both goals. Constructing new facilities to manufacture electric vehicles (EVs) requires significant upfront capital, and lenders and other private investors are instrumental for mobilizing capital quickly. Meanwhile, private real estate developers and government owners of transportation infrastructure rely on capital markets to execute their construction activities, whether they are building new assets or repurposing what has already been built. It is not enough for new technologies and neighborhood designs to be available; investors are necessary to bring those technologies to market.

Yet, as powerful a tool as finance is for modernizing the transportation industry, current financing practices alone will not address underlying inequities within the fossil fuel–powered transportation sector. Based on a detailed analysis of market trends, academic research, and expert interviews, this brief reveals multiple pain points that could limit the speed and reach of the country’s transition to a cleaner transportation system. These pain points include the following:

- Climate accounting is still nascent, and the environmental impacts of transportation emissions are underpriced; both reasons limit long-term private capital flows into cleaner manufacturing and sustainable neighborhood design.

- Low-earning households and businesses may not be able to afford newer EVs, and bringing EVs to market will not address automobile dependency and the related health effects at the neighborhood scale.

- Transitioning to new manufacturing processes could disrupt labor markets in certain places, and adopting EV manufacturing could lead to overconsumption of other natural materials.

Addressing these pain points will require new approaches from policymakers to help transportation activities become cleaner and more equitable. Modernized climate accounting and pricing policies can influence the behavior of investors, manufacturers, and households alike. Zoning and fiscal policies can promote cleaner and more adaptive neighborhood investments. Finally, policy can smooth career transitions for those impacted during the transition to a clean transportation sector.

Introduction

By almost any measure, the transportation sector is an immense component of the U.S. economy. The Bureau of Economic Analysis valued the sector’s combined public and private capital stock at $10.7 trillion in 2022, a measure that includes physical infrastructure like highways and ports and equipment like trucks and aircraft.1 The industries that manufacture vehicles and equipment, plus the companies who move and store goods, produced 9% of total U.S. GDP in 2022. Those same industries employed 15.8 million workers, equal to over 10% of the country’s total workforce.

One of the best explanations for all that value creation is, simply, that transportation is essential. No household or business can prosper without direct access to transportation, whether to move people or to access the goods and services central to daily life. And nowhere is this truism clearer than when one accounts for how America moves. The average household travels over 36,000 miles per year, at a cost of about $12,300 in direct transportation expenses. The freight industry moved about $19 trillion in goods in 2022, with a total weigh of about 20 billion tons.

While all that movement creates economic value, the country’s over-reliance on fossil fuels to power its transportation sector continues to harm the natural environment and public health. The solutions, though, won’t come cheap. Adopting cleaner transportation will require sizable private investment in manufacturing facilities, vehicles, and even neighborhood and community design to help households and businesses reduce their environmental impacts. The only reasonable way to deliver investment at such scale is to tap the power of America’s financial industry.

The goal of this brief is to assess the transportation sector’s environmental impacts, how private financing can help minimize future emissions, and what pain points may hinder efforts to finance a cleaner and more inclusive transportation sector. This research is particularly focused on human and goods mobility, including roadway, railway, aviation, and maritime activities.2 One companion piece focused on energy discusses the assets, activities, and emissions related to petroleum extraction, refining, and pipeline transport; another companion piece discusses adaptation issues for publicly owned transportation infrastructure; and a third real estate piece delves into the subject of altering buildings and urban form.3

The urgent task of decarbonizing transportation

The data is clear: the domestic transportation sector is a drag on America’s climate conditions. Since 2017, transportation activities have emitted the most GHG emissions of any economic sector, surpassing both electricity generation and industry (see Figure 1). Unlike the emissions of those other two sectors, though, transportation emissions have grown since 1990 and barely have improved over the past five years. The emissions produced by all the country’s cars, trucks, aircraft, and other vehicles are also especially dangerous. Their emissions impact the entire country and planet as they move through the atmosphere, and the ambient particulate matter coming from tires, brakes, and tailpipes further degrade local air, soil, and water quality.

At the center of the sector’s poor emissions record are two troubling, interrelated conditions: persistent fuel use and growing demand. Petroleum-based products and internal combustion engines (ICE) are still the predominant power source in every U.S. transportation network. That is especially the case for passenger cars, light-duty trucks, and medium- and heavy-duty trucks. Those three vehicle categories alone accounted for 1,443 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MMT CO2 eq.) of total GHG emissions in 2022. That amount is more than three times larger than all the emissions attributed to either the country’s residential or commercial buildings sectors. Aircraft contributed another 170 MMT CO2 Eq. emissions in 2022, or 9% of total transportation emissions.4 Maritime vessels, passenger and freight rail, and buses only contributed a combined 6% of total transportation-related emissions.5

The other major concern is growing demand. Beginning with households, annual vehicle miles traveled (VMT) among all passenger vehicles rose over 41% between 1990 and 2022, exceeding the population growth rate of 33% during the same period (see Figure 2).6 Not only did people drive more, but they also switched to heavier vehicles like sports utility vehicles at significant rates.7 More miles driven, heavier vehicles, and continued gasoline use is an unsustainable combination—even when corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) regulations have helped those vehicles become more fuel-efficient.

Growing demand in the goods and services trade creates similar downstream emissions challenges. Increasing freight volumes, including both intercity goods trade and the emergence of ecommerce, led total VMT among medium- and heavy-duty trucks to rise 127% from 1990 to 2022.8 While the national truck fleet did get more fuel efficient, those efficiency gains were not large enough to counteract the increasing volume of goods being transported.9 Meanwhile, more business and leisure travel led commercial airlines to carry 41% more passengers between 2000 and 2023, driving up overall emissions from the sector. Moreover, the domestic economy’s growing sophistication also means greater demand for the kinds of high-value, low-weight products in which air freight specializes.

The overarching challenge for the transportation sector, then, is to find a way to limit emissions without restricting economic activity in the process. This isn’t a uniquely American situation, either. The United Nations (UN) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report in 2023 found that transportation was “the largest energy consuming sector in 40% of countries worldwide” and the second-largest in most others—and petroleum products were the primary energy source in every country. Simply put: the entire planet needs to shift to cleaner transportation fuels.

Technical opportunities and challenges

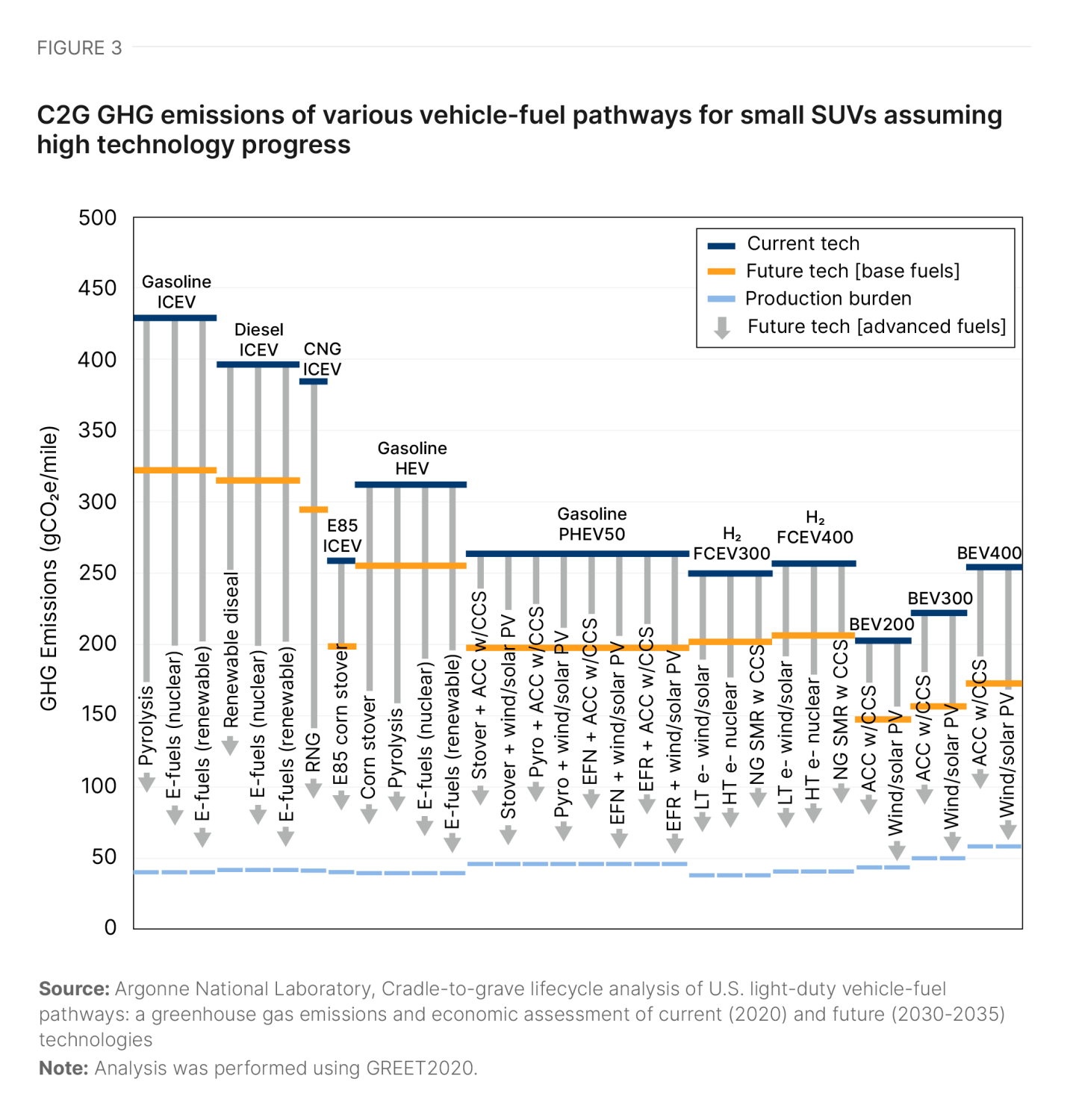

Electrifying the transportation sector could address both core issues, especially in the passenger car and light-duty truck markets. Decades of research, development, and market testing now give households and businesses plenty of new products to choose from including battery electric vehicles (BEV) that rely solely on battery power, hybrids (including plug-ins) that include electric and ICE vehicles, and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. All these fuel and storage technologies promise to produce significantly lower annual tailpipe emissions than conventional gasoline or diesel vehicles, even when accounting for upstream emissions. From a consumer perspective, this is the fastest way to reduce the carbon footprints of households and businesses without changing how people get around (see Figure 3).

There is also a business case for automakers, vehicle suppliers, logistics-related companies, and their outside investors to transition to cleaner vehicles. Reducing vehicle emissions makes the entire automotive sector more climate friendly, enhancing the long-term viability of these related industries. Newer products could open up new paths to profitability, as many vehicles and kinds of equipment have higher price points, even after including heavy retail discounts.10 Putting aside past and ongoing R&D efforts, this business case is the central reason manufacturers have announced $188 billion into new and retrofitted facilities since 2015, a total that appears to be equal to roughly half of the industry’s total capital expenditures over this period (see Figure 4). There is a similar motivation for the logistics industry—including ecommerce companies—which has put in orders for tens of billions of dollars in battery electric trucks and, in some cases, has directly invested in manufacturers.11

The electrification of the car and truck industry is also poised to disrupt the labor market—requiring workers to gain new skills and competencies to manufacture, install, and maintain these technologies. The need to upskill and reskill a generation of talent poses considerable costs to employers, educators, and workers themselves, but this task has the potential to open up new career pathways to the country’s transportation workforce, too. With over 1 million people currently working in automotive manufacturing, investments in EV manufacturing could support the sector’s existing workforce, but these investments also could drive the creation of new jobs in new facilities.12 There is also potential for net job creation via battery-related activities, grid-related occupations, and other production activities.13 And with even larger numbers of people currently working in transportation-related service industries—including vehicle maintenance, transit agencies, and freight deliveries—electrification could help sustain many of those jobs.

Yet vehicle electrification cannot solve all of the transportation sector’s emissions issues, today or in the future. Current vehicle technologies also still need to improve. While market penetration is growing quickly—and many more vehicle models are on the way—there is a continued need to invest in cleaner batteries and vehicle designs for passenger cars and light-duty trucks. Ideally, the production of those innovations can use more sustainable raw and processed material inputs, consume cleaner energy at mining and manufacturing sites, and reduce vehicle weights. Buses, medium-duty trucks, and heavy-duty trucks would benefit from the same innovations, particularly as EVs start from an even lower market share among those larger vehicle classes. The maritime and aviation industries face the steepest needs, as there simply are not market-ready technologies to allow significant reductions in their fossil fuel use, although extensive research is underway into sustainable aviation fuels.

Electrification’s environmental benefits also depend on having an electric grid that supplies clean and abundant electricity—something most states do not yet have. There is a major difference in the emissions levels associated with electricity generated from coal and natural gas versus renewables and nuclear power (see Map 1). Tapping the full emissions benefits of EVs, then, requires a similar transition to clean electricity across the entire country. Likewise, the electric grid will need sizable investments to keep up with the growing adoption of EVs, including new long-distance transmission lines, improved local distribution systems, and inverters to allow batteries to shift electricity back onto the grid.14 By some estimates, just those grid-related investments could cost between $10 billion and $25 billion by 2030.15

Much of America still requires significant investment in electric refueling infrastructure, often called electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE). While 64% of U.S. adults do live within two miles of a public charging station, ongoing reliability issues and concerns around charging demand outstripping supply indicate that the country needs far more public charging infrastructure. In-home installations are available and affordable to many households. However, there are 44 million households who live in multiunit housing and may not be able to install their own chargers, while millions of others may not have the financial means to afford an in-home installation. Charging infrastructure and product quality should have a sizable impact on overall demand for EVs. There are similar needs on the freight side, including technologies that can reduce the time needed to charge heavier trucks on highways, within port complexes, and elsewhere.

Even if fuel-related emissions approach zero, emissions are deeply entrenched in other vehicle-related technologies. The regular wear-and-tear of rubber tires and vehicle brakes emit significant ambient particulate matter, all of which can directly harm human health and degrade ocean health. Since EVs weigh significantly more than comparable ICE vehicles, their adoption may exacerbate non-exhaust particulates depending on tire and brake technologies. Likewise, continued driving necessitates ongoing roadway construction, which itself leads to greater emissions through cement and asphalt production. Heavier vehicles will degrade roads faster and necessitate more frequent road construction.

Other barriers to decarbonization

Beyond technologies, there are other barriers to decarbonizing the transportation sector. Consumer attitudes toward EVs are an ongoing concern. Polls reveal that driving distances and the availability of charging stations are common worries, both among U.S. and global drivers. Consumers increasingly understand that colder weather and heavier payloads can limit the distances an EV can travel. EVs also continue to be more expensive than comparable ICE models.16 While EV market penetration continues to grow each year, these concerns could put a ceiling on household adoption.

Established parties who benefit from petroleum use could flex their political muscle to slow or discourage the transition to a clean transportation sector. The threat of stranded assets will continue to push companies in the business of oil and gas extraction, petroleum refining, and fuel transportation and delivery to lobby against electrification. Workers in those industries could also be supportive of such efforts.

Policy uncertainty is another barrier. The country’s two main political parties deeply disagree on the need to decarbonize the economy and—even among officials who do see the need—how much public policy should incentivize such decarbonization. In the case of the transportation sector, shifting CAFE standards between the administrations of former President Barack Obama, former President Donald Trump, and President Joe Biden are a prominent example. Such policy uncertainty introduces investment risks for manufacturers and service companies.

Finally, the United States faces much higher barriers than peer countries do when it comes to switching from the use of one transportation mode to another. While EVs may be cleaner than ICE vehicles, the cleanest form of transportation will always be walking, biking, taking transit, or—in the case of telecommuting—avoiding any movement at all. The U.S. federal government and the UN recognize that mode shift would offer large climate benefits as well as significant public health benefits and lower infrastructure costs per capita for governments.

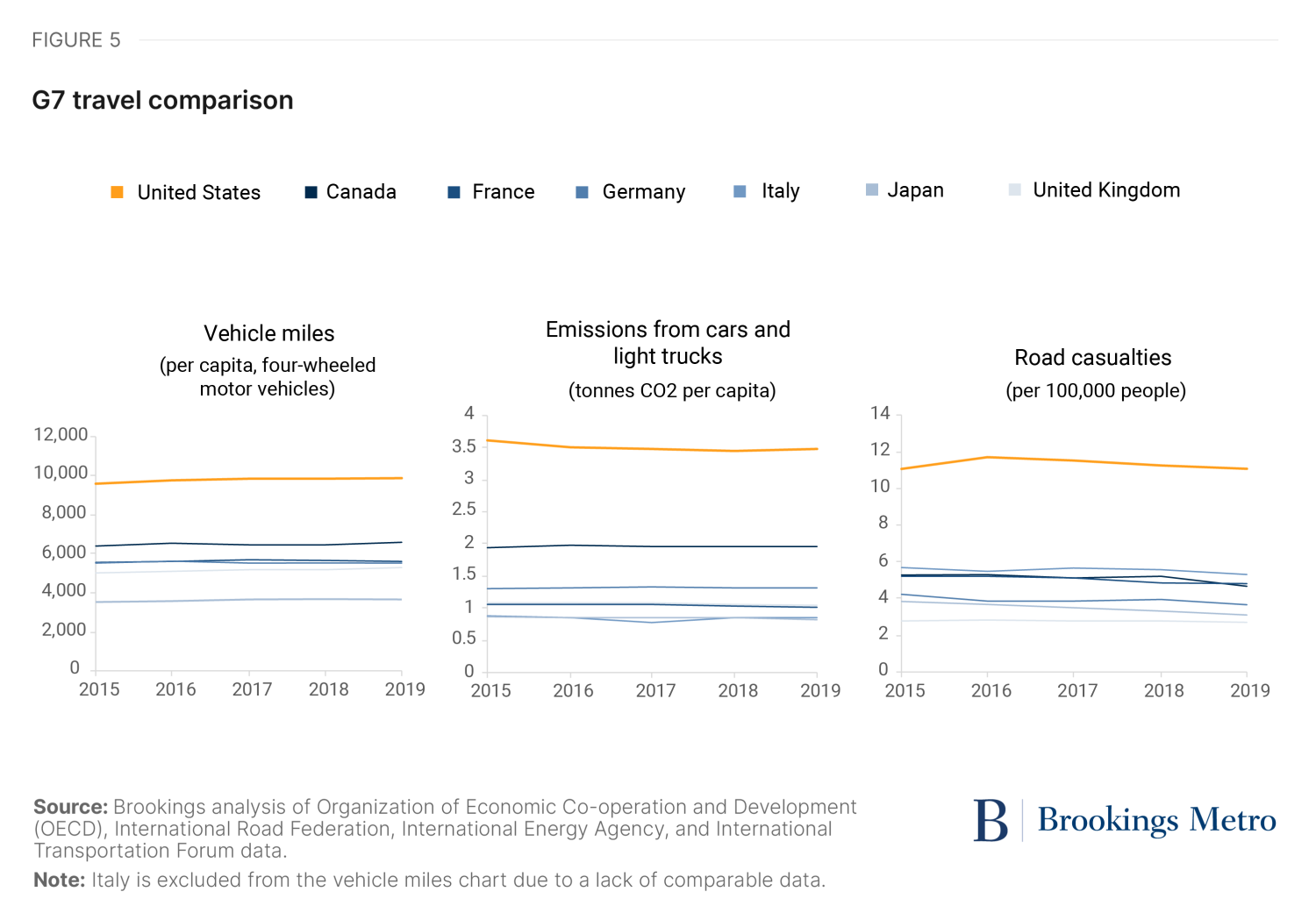

Yet Americans, by far, drive the most miles and use their cars for the highest share of trips compared to any of the other G7 members (see Figure 5). This is not by accident. Decades of automobile-oriented development policies prioritized building roadways and single-family homes at the expense of bike lanes, rail lines, multi-unit buildings, and denser neighborhoods. One of the legacies of that development model is that most metropolitan households will struggle to adopt more active transportation modes, even if they are interested in doing so.

Financing cleaner forms of transportation

No matter the pathways chosen, transitioning to more sustainable transportation options will require significant upfront investment. Manufacturers must construct new plants or retrofit existing ones. Freight firms and other shippers need to purchase new vehicle fleets. Households will pay higher prices to buy EVs, install in-home chargers, or often both. Building more travel-efficient neighborhoods will be expensive, too. And time isn’t on the country’s side: it needs to reduce transportation emissions as quickly as possible.

Financing—or the process of providing or raising upfront funding for business activities—is an essential component of any attempt to clean up the transportation sector on an aggressive timeline. For example, scholars Hong Yang and Lewis Fulton estimated in 2022 that industry will need to invest up to $140 billion in vehicle manufacturing to hit 2030 sales targets for electric cars and light-duty trucks, and the commitments at the time of publication fell tens of billions short. The aviation, railroad, seaborne, and truck transportation industries will need to retrofit much of their equipment, which is currently valued at over $500 billion. Each household will need to spend tens of thousands of dollars to purchase a new or used EV.

Fortunately, the United States benefits from a long-established relationship between the transportation sector and the financial industry. All the major actors responsible for delivering a more sustainable transportation system regularly use private financing to acquire capital assets, whether they do so by investing in their physical establishments, constructing new infrastructure, or purchasing vehicles. However, not all established financing practices—even if they efficiently allocate capital—necessarily promote a cleaner transportation system. The threats vary depending on the actors involved.

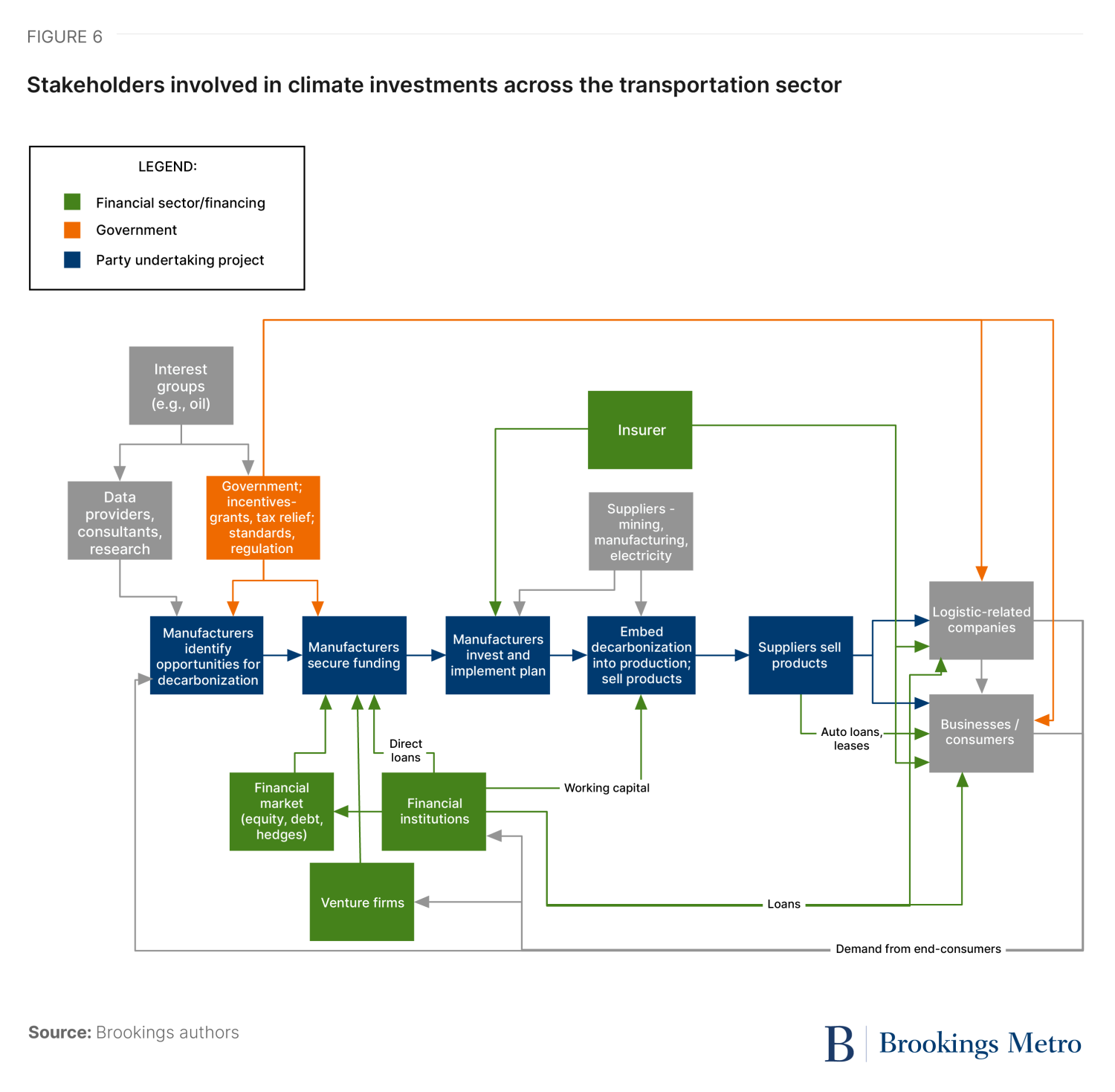

See Figure 6, for instance. This flow chart focuses on the key actors responsible for vehicle manufacturing and consumption, not redesigning neighborhoods. For more information on the actors involved in financing residential and commercial real estate, see a companion brief on buildings.

Transportation sector manufacturers and related production

Transportation-related manufacturing is a capital-intensive business, requiring significant upfront investment in R&D; plant equipment; and the workforce to build all those cars, trains, ships, and aircraft. For example, transportation manufacturing industries alone spent $51 billion in 2022 for new structures and equipment. And like every capital-intensive business, private investors help provide upfront financial capital to make those investments, typically by using direct loans (including project finance), purchasing corporate debt securities, or purchasing equity in a company. Many manufacturers and investors also use more complex instruments, like price hedging against the costs of raw material inputs and currency rates. Manufacturers with significant cash resources or profitable business lines can also effectively self-finance new capital investments by internally subsidizing new business lines. No matter the complexity, all these instruments are well-established financing pathways that all manufacturers should be aware of, whether they are century-old companies or year-old startups.

Even with established capital-deploying and capital-raising channels, there are significant risks related to financing cleaner manufacturing. One of the biggest risks is the combination of technological timing and shifting demand. Investors are likely to be more patient if they believe a company’s current technologies are not under threat, whether that’s the equipment used in a manufacturing plant or how well the final products can sell within a given consumer segment. But the opposite is also true: once low- and zero-carbon technologies become available, market demand can shift. Regulators often wait for technologies to be market-ready before they adopt more rigorous environmental standards—but once regulations are in place, current equipment and manufactured products can quickly become obsolete.

Consider aircraft and ship manufacturing. Since there is no current technological path to building low- and zero-emissions aircraft and vessels in the immediate future, manufacturers can feel more confident in stable demand for their current products—and investors are likely to feel the same. It’s the opposite for car and light-duty truck manufacturers. There is a reason why both higher-risk venture capital and lower-risk institutional investors are financing EV manufacturers: they make a product that is poised to stay in demand and accommodate CAFE standards.17 Investors particularly have a self-interest in keeping older companies in business, since most carry large debt loads. And once technologies are ready to be adopted at scale, investors may see new products—from battery production to final vehicles—as a way to capture profit-making opportunities.

It’s fair to say, then, that manufacturers who build clean transportation technologies could be in a relatively advantageous position. Clean manufacturers benefit from the many major investors, including large institutions and venture capital firms, who have increased the share of their portfolios committed to green companies and that have begun divesting from companies that they classify as heavy polluters. Clean manufacturers also can qualify for investment through exchange-traded funds that focus on clean technologies, including battery- and vehicle-related activities. Finally, clean manufacturers can access cheaper financing from investors who will accept less favorable terms to invest in cleaner technologies (or what’s sometimes called a “greenium”). In fact, the Inflation Reduction Act codifies such financing advantages for clean transportation manufacturers.

Political economy is another risk factor. If federal or state officials decide to weaken emissions standards or roll back clean manufacturing incentives, those reforms should reduce private investor and manufacturer interest in investing in clean technologies. One specific threat comes from manufacturers of and investors in high-polluting products, who—when facing obsoletion—could lobby for unsustainable policies to extend the useful life of their products and investments. Ongoing debates around the safety of mineral extraction threaten to inflame issues related to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards. And while sales of EVs and electric bikes continue to grow each year, cooling consumer demand for clean transportation products could have a similar chilling effect on public officials.

Policy gaps and related inconsistencies exacerbate such political risks. The country’s nascent climate accounting rules, including those around disclosures, make it more difficult to connect climate burdens to specific manufacturing activities. Likewise, the lack of emissions pricing limits the power of market signals to influence the behavior of manufacturers, investors, or consumers. Where pricing does exist—in the case of carbon credits—the impact of the pricing instruments is tied to the stringency of emissions standards, which themselves are inconsistent across federal administrations.

Finally, workforce deficits are another potential risk to efficient manufacturing investment. While much of the knowledge and many of the skills are the same between higher-polluting and cleaner manufacturing, not all are. Certification and licensing may also need to shift in the EV transition, causing further strains on workers. Companies and their local workforce partners—including community colleges, unions, and workforce investment boards—are responsible for making sure there is a well-trained labor pool available to mine materials, manufacture products, and even construct new facilities. If there’s not, though, costs could rise—due to factors such as extended construction timelines or more extensive assembly line disruptions—and limit borrowers’ ability to repay. Critically, it may be difficult for investors to see these risks before they agree to finance a project or company.

Transportation service providers

While many manufacturers are synonymous with transportation, service providers leave a far larger industrial footprint. Car mechanics, transit agencies, trucking firms, commercial airlines, railroads, and maritime shippers—plus many more kinds of service firms—collectively employ over 9.3 million people. They also sold goods and services worth $1.4 trillion in 2023, more than four times the GDP contributions of all transportation-related manufacturers combined.18 Of course, the service industry is the opposite of monolithic. Services offered and company sizes vary widely, ranging from mom-and-pop establishments that tune up cars to global companies that ship containers around the world.

Even with such variety among these businesses, all the major transportation service industries are well-connected to the financial services industry. Local lenders—ranging from small credit unions to national banks—help local-serving companies to purchase equipment or simply keep lines of credit open. National financial firms help larger companies sell equity, issue debt, and take part in larger exchanges, all of which can help provide large upfront financial capital to invest. Some sectors, especially commercial airlines and logistics companies, make use of specialized financing instruments like loan securitization, derivatives, and energy hedging to stabilize their fiscal positions. On the public side, transit agencies, school districts, and other local and state units of governments turn to municipal debt markets to secure financing for upfront investments in their fleets and related infrastructure. Federal programs like the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund and state entities like green banks are designed to help finance projects, particularly for localities and specific projects with financing gaps. Manufacturers can even function as lenders to service providers, as many offer leasing models to boost sales of their trucks, aircraft, ships, and other high-priced equipment.

It’s no surprise, then, that transportation service providers face many of the same financing threats as transportation-related manufacturers. For providers whose core technologies are not yet ready to decarbonize—in industries such as commercial airlines and air shippers, maritime freight, and heavy trucking—decarbonization presents less of a threat to current business models and equipment. Where clean technologies are ready to scale—in sectors such as personal vehicles as well as first- and last-mile delivery—then current service providers and their financing partners need to be ready to invest in cleaner equipment, particularly as many non-transportation companies look to operate their supply chains through lower-emitting freight services. And like manufacturing, investors have the ability to pressure service providers who are not adopting clean technologies fast enough.

Here, too, political economy and workforce issues have the power to accelerate or disrupt investments. Regulators in different states and localities do mandate different emissions standards for a whole host of transportation modes, including household vehicles, public transportation vehicles, on-road trucks, and vehicle use at ports. A shortage of well-trained workers could disrupt new clean technology operations, like extending maintenance timelines for electric school buses.

One additional concern is information asymmetry or general knowledge gaps among smaller businesses. While it is easy to imagine that larger companies and large financial firms understand how to balance climate risks against other business considerations, smaller businesses and more local investors may not be aware of just how much the clean economy transition could impact their businesses. For example, if local auto mechanics are not prepared to service BEVs, then their businesses could struggle as the EV transition gains steam—and any loss of business could impact their lenders upstream. Since there are few established accounting standards around climate risk, especially when compared to traditional financial accounting, smaller financial firms may want to ensure that they are studying their portfolios for potential climate contagions.

Remaking America's fueling infrastructure

Gas stations are synonymous with America’s automobile age—and for good reason. Over 111,000 gas stations were open for business across the country in 2020, and they employed almost 1 million workers. Yet for all their convenience and their penchant for keeping cars on the go and satisfying snack cravings, today’s gas stations are ill-equipped to fill the same role in the EV era. It currently takes longer to charge an EV battery than it does to fill a gas tank. Many households will prefer to refuel their EVs at home. With so many gas stations in every community, America needs a grand rethink around the quantity, design, and financing of vehicle fueling infrastructure.

One massive set of questions revolves around what to do with all the existing stations. Many will close due to less demand, but it will require serious environmental remediation to safely prepare the land for future development. Municipalities and even states will want to know who is financially exposed to the business losses, what properties can self-finance their redevelopment (like those at high-demand intersections), and where the public may need to intervene.

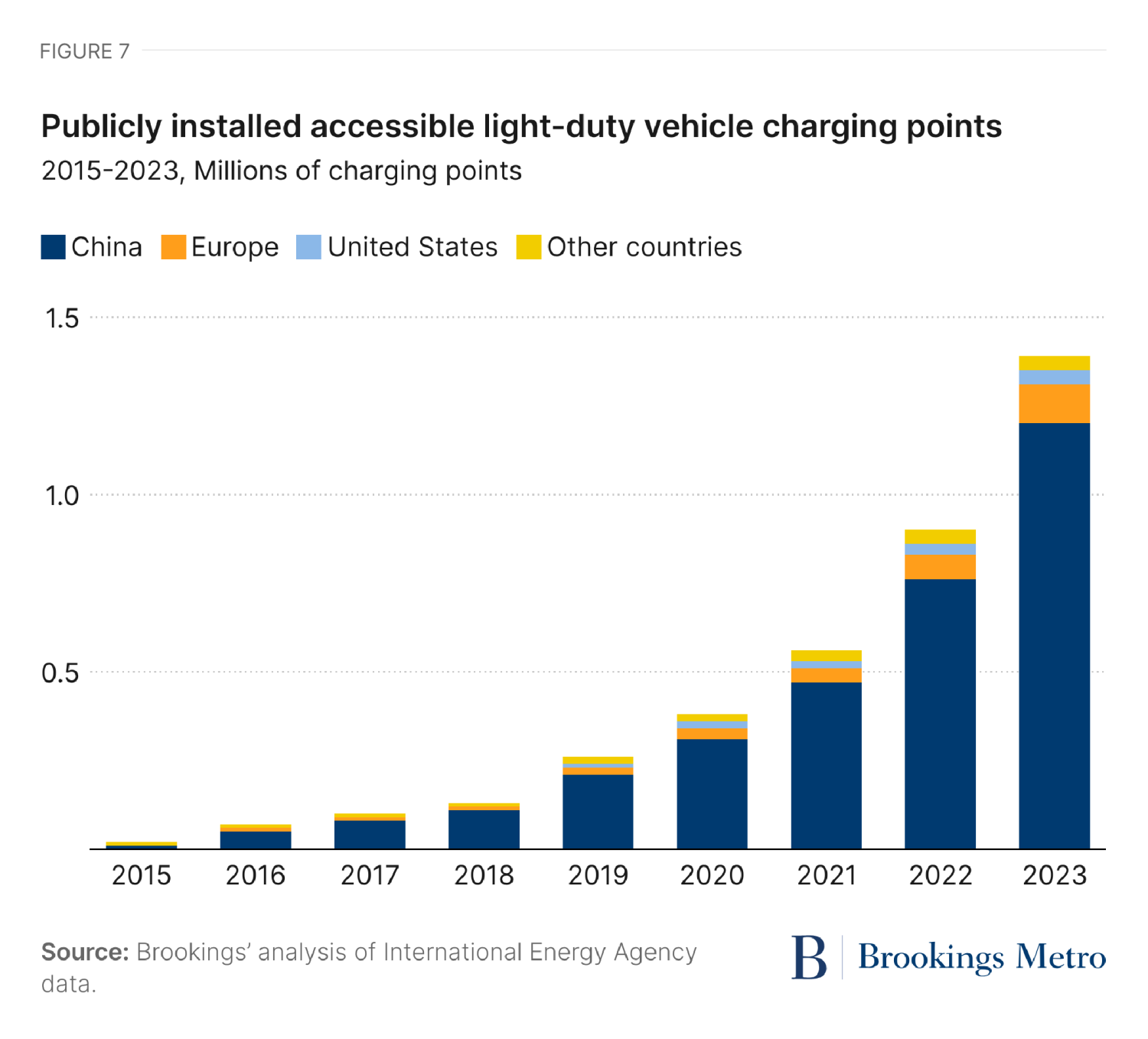

The other major area of need is how to deploy charging infrastructure at scale. While the public sector is leading some investment—most notably the federal government’s National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Program—financial markets are a more dependable, long-term capital source. As it stands, the U.S. trails Europe and China in terms of fast, public charging installations and public charging capacity per vehicle (see Figure 7).

Financing at scale, though, requires dependable revenue streams, and this is where information gaps become problematic. How many EV users will charge at home? What prices are people willing to pay to charge their EVs in public, and who should regulate the rates? What should be the relationship between electric utilities, charging station owners, and vehicle manufacturers? What station amenities are necessary to keep people occupied for the time it requires to charge their vehicles—or will better battery technology keep current gas station designs competitive?

Progress is underway. Banks, other consumer lenders, and even some utility companies now offer products to help multi-unit developers and homeowners install chargers. Current charging is helping providers collect a universe of data points on the customer experience. Companies, including startups, are testing stations for the EV experience that are designed from the ground up. As long as EV adoption keeps growing, investors and their partners are likely to keep trying new interventions to help answer these questions.

Household financing

On average, transportation is the second-largest annual household expense after shelter.19 This is not typical when making global comparisons—and that is because Americans simply drive more miles per capita than their peers. All the costs to purchase, maintain, insure, and fuel a car really add up, especially for lower-earning households who choose to drive. Vehicle-related inflation since 2020 only made the price barriers higher, and spending on most vehicle-related items is growing faster than that on overall consumer items (see Figure 8).

To satisfy their demand to drive and help cover high ownership costs, Americans make heavy use of private loans to help spread costs over a longer period. Outstanding auto loan debt stood at $1. 6 trillion at the end of 2023, a figure that has doubled since 2012.20 While most loans are repaid on time (typically around 98%), more borrowers have become delinquent in 2023 than before the COVID-19 pandemic, with the lowest-income borrowers seeing their delinquency rates rise the fastest.

Multiple types of lenders operate in the auto lending space. In addition to traditional lenders like commercial banks and credit unions, automakers are major players, with their financial products often offering greater profitability than their core productive activities. Online auto retailers and new fintech companies are also moving into the space. Lenders continue to experiment with new products, too, like bundling in-home charging installation with vehicle loans.

Generally speaking, the transition to a clean transportation sector does not raise any serious systemic risks among auto industry lenders. EVs do have higher sticker prices at the moment, but the underlying commodity is the same: a car. There are underlying questions around depreciation schedules, as there are not enough EVs in use yet to understand how long vehicles will stay operational with regular maintenance. If EVs cannot last as long as currently expected, then it is possible that lenders with high EV exposure could face unexpected losses.

The real financing risk is to American households who feel compelled to drive, cannot truly afford a personal car, but still use loans to purchase a vehicle. The cost burden on lower-income households is clear in the data, and many will be unable to afford EVs. Lower-income households are also more likely to hold onto older ICE models, many of which could then become more expensive to maintain and refuel.

The overall efficiency of the auto loan marketplace raises a more existential climate concern: auto loans reinforce America’s driving addictions. To shift away from so much driving and reduce household spending, America must better connect transportation and real estate financing. The most sustainable household travel is done by walking, biking, and using transit. Each are extremely low-cost options for any household, even purchasing a traditional or electric bicycle. However, most American communities do not offer the kinds of physical proximity that make non-driving trips safe or attractive. It may not cost households much to use more active transportation infrastructure, but it will require significant real estate financing to retrofit communities for greater proximity. The challenge, then, is addressing an information breakdown between emissions accounting: there is no current way to give real estate developers credit for building properties that reduce the transportation emissions of the residents and tenants. Most municipalities also do not use climate costs and benefits to influence their zoning and fiscal decisions, which effectively disassociates the resulting climate impacts from local transportation behavior.

Current private finance practices will do little to address transportation inequities

Ideally, all modes of transportation should be accessible and affordable to every household and business, regardless of where people live or what financial means they have. Transportation should also be safe, both for people and the natural environment. America’s current transportation system does not hit those targets—and transitioning to cleaner technologies will not necessarily address each factor, even certain elements of environmental quality. In other words, current financing practices and government regulations do little to address these long-standing transportation inequities.

While finding cars and trucks to buy is not hard—and there are plenty of roadways and parking lots to put vehicles to use—affordability is a major ongoing concern. Lower-income households are the least likely to be able to afford the higher upfront costs of cleaner vehicles and charging equipment, and the data is already bearing this out. They are also likely to face higher borrowing costs if financing either purchase, and there are reasons to be skeptical over whether the public sector should help zero-vehicle households acquire vehicles they may not be able to maintain. There is a similar set of concerns for service businesses that have uneven cash flow, have difficulties using technology, or are more likely to be denied credit. And since female- and minority-owned small businesses are more likely to meet these criteria, it is fair to worry that such enterprises will be less able to transition to EVs.

The same affordability issues will appear at the community level, too. Decades of spatial and economic development patterns have often led to income concentrations at the neighborhood level, specifically concerns around concentrated poverty. Investors and companies may also be hesitant to build chargers if there are few EV users in a given neighborhood. The net effect is likely to be lower EV adoption in lower-income neighborhoods, which also means those neighborhoods are more likely to experience heightened air pollutant levels from continued use of ICE vehicles. Current data already reveals such inequitable patterns to public charging infrastructure. While current law around nonattainment of ambient air quality standards incentivize action at the regional scale, laws may need to be amended to account for equitable pollution concerns in the EV era.

The transition to cleaner cars and trucks is also likely to reinforce accessibility gaps for more affordable modes of travel. The more America commits to manufacturing and using vehicles, the more communities will be built to accommodate them. The continued loss of proximity creates barriers to transportation affordability. There also are few government regulations that incentivize greater financial incentives for real estate developers who build communities that do promote proximity. As a result, American government units—most notably transit agencies—have struggled to find ways to capitalize on the denser development opportunities that can be created through proximity-focused transportation investments like new rapid transit lines and bike lanes.

Nor will the switch to cleaner vehicles make America’s streets any safer. The country is already in the middle of a troubling reversal in traffic safety, with fatality rates up 25% between 2013 and 2023. If anything, there are already concerns that EVs’ quieter transmission will decrease pedestrians’ awareness of fast-moving vehicles without noisemakers. Here, too, there is no obvious way that private finance can address long-standing safety concerns. It is ultimately the responsibility of the government to enforce safe vehicle designs and protect people at the community level.

Environmentally, the EV transition should deliver significant benefits. Reducing the transportation sector’s total emissions will benefit the planet’s atmosphere and mitigate climate change, a truly public good enjoyed by everyone.

But there are areas of environmental concern with EVs, including the environmental toll from the extraction of raw materials, the excess particulate matter emitted due to greater tire and brake use, and the excessive road maintenance needed due to greater vehicle weights. There is a non-zero chance that neighborhoods and communities that adopt electric cars and trucks at greater rates will experience more local air pollutants like large particulate matter than they do today, causing even greater air, water, and soil quality issues in the process. It is paramount that data monitoring help track how local emissions change with the adoption of EVs.

Could financing passenger rail address a major accessibility gap in the push for a cleaner transportation sector?

America’s passenger rail has seen better days. While the country once offered one of the world’s best passenger rail networks—many metro areas are still spaced perfectly apart for the service—current intercity rail service is spotty. And outside the corridor running roughly from Boston to Richmond, Virginia, the lines that do exist tend to carry fewer passengers than competing travel modes. Yet with a mix of slow speeds and infrequent service, it is hard to blame consumers for choosing higher-polluting cars and planes.

But based on the global experience and parts of the Northeast Corridor, the evidence is clear that high-speed rail can become the dominant choice for intercity travelers in the right corridors. And unlike clean aviation fuels, high-speed rail technology is already electrified and ready to scale. The issue is that the U.S. has struggled to find enough public funding to build new rail lines and affordable train sets to match market demand. This is a clear market opportunity for private finance. Whether it means helping to launch new privately owned services like Brightline, supporting publicly backed services like Amtrak, or empowering state rail agencies to build new ties with private investors, financiers could be the missing ingredient to accelerate America’s next great wave of fast—and clean—intercity transportation.

Putting aside the social equity concerns related to how the country’s inhabitants move, there are also threats to the industries and workers who help make all that movement possible. Like most tradable industries, transportation manufacturing and freight activities concentrate in specific places, particularly in the industrial Midwest, the South, and certain coastal and border metros. Not surprisingly, these same places tend to be hubs for transportation workers, too (See Maps 2 and 3).

As underlying transportation technologies change, there is a genuine threat that certain metro areas will be winners and losers in the race to secure the next wave of transportation industries. Some of these geographic shifts are already in motion. After decades of attracting foreign direct investment to host foreign automaker operations, the southern auto belt is now also securing investments to build new EV and battery manufacturing facilities. Meanwhile, many parts of the Midwest appear poised to hold onto manufacturing due to retrofitted facilities and new ones. Change in the structure of logistics and last-mile-delivery businesses could have similar repercussions and already have with the emerging presence of digital technology–focused companies in Seattle and elsewhere along the Pacific coast. Such industrial transitions will also require many workers to learn new skills or gain new credentials, yet lenders do not tend to require companies to demonstrate these types of workforce development activities to secure financing.21

These spatial patterns bear watching, particularly because the country is well-versed in the consequences of lost manufacturing on entire metro areas. Here, too, there are no obvious answers for how financing could address economic decline or help ensure that workers access needed training, retraining, and supportive services.

Finally, smaller companies within the freight industry have long been unable to match the scale economies of many larger third-party logistics companies and similar peers. Companies with easier access to financial capital, including the ability to secure more favorable lending terms, would have an advantage in terms of transitioning to cleaner vehicles quickly and at scale. Disadvantaging smaller freight firms could impede their wealth-building and wealth-retention opportunities relative to the industry as a whole, a challenge that merits monitoring by public officials.

Conclusion

Transitioning to a clean transportation network is one of the most important climate projects in the U.S. in the coming decades. Reducing emissions from all the country’s driving, flying, and shipping can make a significant dent in total U.S. emissions, helping to meet the country’s global and domestic climate pledges. Adopting cleaner technologies can build economic resilience among domestic transportation industries, creating long-term value for business owners, employees, and investors. And just as importantly, a cleaner transportation network can improve the well-being of every person, every business, and every community, especially if it includes neighborhood redesigns.

Finance is a critical lever for cleaning the country’s transportation system and for doing so on an accelerated schedule. Technologies are available to reduce GHG emissions, and finance will help build new factories and modernize commercial and household vehicle fleets quicker.

Yet finance alone cannot solve all the country’s concerns regarding transportation emissions. Resetting vehicle lock-in will continue to threaten the public health and safety of all neighborhoods, while certain households may struggle to afford EVs. The EV transition could also upend many workers’ livelihoods, creating new stressors among certain regional economies. Even if financing is well-established across the industry, it is incumbent on public policy to complement capital flows to deliver both a cleaner and more equitable transportation system.

Equitable climate finance series

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Funding for this research was provided by HSBC Bank USA, N.A. The program is also grateful to the Metropolitan Council, a network of business, civic, and philanthropic leaders that provides both financial and intellectual support to the program. The views expressed in this report are solely those of its authors and do not represent the views of the donors, their officers, or employees.

-

Footnotes

- Note the bureau’s measure is net value, which includes the value of total investment less depreciation.

- Intermodal references goods trade that uses a combination of multiple modes without handling the freight during its movement. This brief captures intermodal activities by subdividing activities across the other four modes.

- Pipelines transported over 80% of all barrels of combined petroleum products from 2019 to 2021.

- Commercial aviation operations were still lower in 2022 than the pre-pandemic levels in 2019, meaning that there is a high likelihood that commercial aviation emissions—the primary driver of total aviation emissions—were significantly higher in 2023 as passenger levels rebounded. See Bureau of Transportation Statistics reporting for consistently updated traffic figures.

- Since the U.S. Energy Information Administration only counts emissions from domestic transportation movements, both the aviation and shipping sectors would have higher total emissions if counting international transportation.

- Source: Brookings’ analysis of Federal Highway Administration (Highway Statistics, Table VM-1) and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis data.

- See Figure ES-2 in the linked report.

- Source: Brookings’ analysis of Federal Highway Administration (Highway Statistics, Table VM-1) data.

- Ibid.

- At the time of publication, there are ongoing debates about whether EVs will maintain a price premium relative to ICE vehicles and about how ongoing capital investments could create new pathways to profitability, including greater manufacturing efficiency at lower price points. For one example from a European context, see Vanessa Lyon, et al., “The High-Stakes Race to Build Affordable B-Segment EVs in Europe,” Boston Consulting Group, October 2023, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/reducing-the-electric-vehicle-manufacturing-costs. For a more recent journalistic perspective, see Ben Glickman, “EVs Are Cheaper Than Ever. Can Car Buyers Be Won Over?,” Wall Street Journal, July 22, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/business/autos/ev-prices-falling-weaker-demand-4be05af6.

- Some of the most prominent orders include Amazon’s $7 billion order with Rivian in 2019, Walmart reserving 5,000 BrightDrop (a General Motors’ subsidiary) vans, and the U.S. Postal Service’s purchase of 66,000 delivery trucks.

- See the January 2024 stats. (See NAICS 3361-3.)

- Employment estimates vary significantly.

- It is important to note there is no one national electric grid, but instead many local grids linked through three interconnections essentially operating independent of one another.

- For a lower estimate, see Bart Ziegler, “Can the Power Grid Handle a Wave of New Electric Vehicles?,” Wall Street Journal, February 5, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/url-us-power-grid-electric-vehicles-ev-charging-11675444994. For a higher estimate, see Michael Hagerty, Sanem Sergici, and Long Lam, “Electric Power Sector Investments of $75–125 Billion Needed to Support Projected 20 Million EVs by 2030, According to Brattle Economists,” Brattle Group, 2020, https://www.brattle.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/19421_brattle_-_opportunities_for_the_electricity_industry_in_ev_transition_-_final.pdf.

- Market analysts continue to track when price parity between EV and ICE vehicles may occur.

- Federal agencies announced updated final rules for CAFE standards in June 2024.

- Brookings’ analysis of Lightcast data.

- Brookings’ analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Expenditure Survey data.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Household Debt and Credit Report, (Q1 2024).

- This finding is based on expert interviews. Please note that government financing through the Inflation Reduction Act can include certain workforce benchmarks.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).