What the US can learn from rental housing markets across the globe

Editor’s note: In case you missed it, watch an event held on April 21 discussing lessons from around the world related to policies to support stable, affordable rental housing.

The COVID-19 pandemic’s enormous economic shock has stressed U.S. housing markets—particularly for the nation’s 44 million renter households, many of whom face escalating costs and deteriorating financial stability. Other countries around the world, too, face these challenges, but do so with sometimes vastly different legal systems, financial instruments, and policy frameworks underpinning their real estate markets.

With that in mind, we believe that this is a good moment to ask what lessons the U.S. can learn from other countries about helping people pay their rent. How are rental housing markets structured in other countries? What kinds of financial subsidies and legal protections do other countries’ renters have? Do other countries have similar challenges with housing supply?

To answer these questions, we asked researchers who study France, Germany, Japan, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States to summarize key features of rental housing markets in those countries. We chose these countries because they have broadly similar household income levels (a key determinant of housing demand) and comparable financial systems (access to capital is crucial for housing development). However, their other economic, legal, and policy elements that influence housing markets are quite different—producing key variations in rental markets.

In this piece, we highlight a few of the important lessons drawn from comparing the six countries. Readers can also explore a wealth of specific details in each of the countries’ respective case studies.

Rentership rates are correlated with income—and with policy choices

In each of the six countries studied, renter households have lower incomes and wealth than homeowners. This relationship makes economic sense: Purchasing a home is a long-term financial commitment, and high-earning households can more easily save for a down payment. At the national level, homeownership increased in most countries during the post-World War II decades as the national economies strengthened.

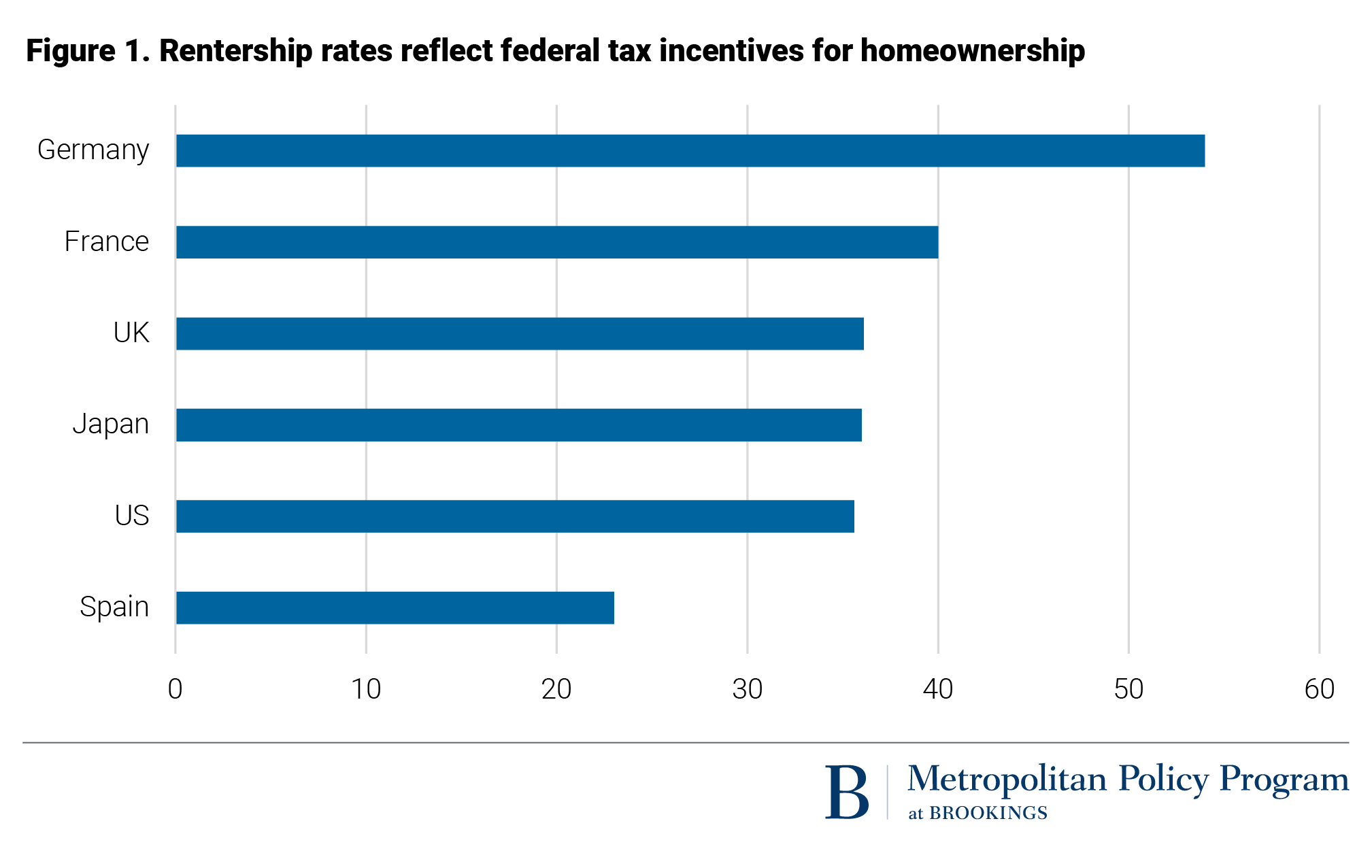

But public policy—especially tax policy—also plays a big role in the relative size of rental and owner-occupied markets. Across the six countries, rentership rates vary from 23% (in Spain) to 54% (Germany). Notably, Germany offers the least generous tax benefits to homeowners; all of the other countries have explicit goals of encouraging people to own. Germany’s tax policy is the inverse of the U.S. mortgage interest deduction: Property owners can deduct the interest paid on a mortgage from income taxes only if the owners do not occupy the property.

(Sources: Acolin 2021; Crump and Schuetz 2021; Hilber and Schoni 2021; Ouasbaa and Viladecans-Marsal 2021; Schmidt 2021; Yoshida 2021)

The many different types of ‘landlord’

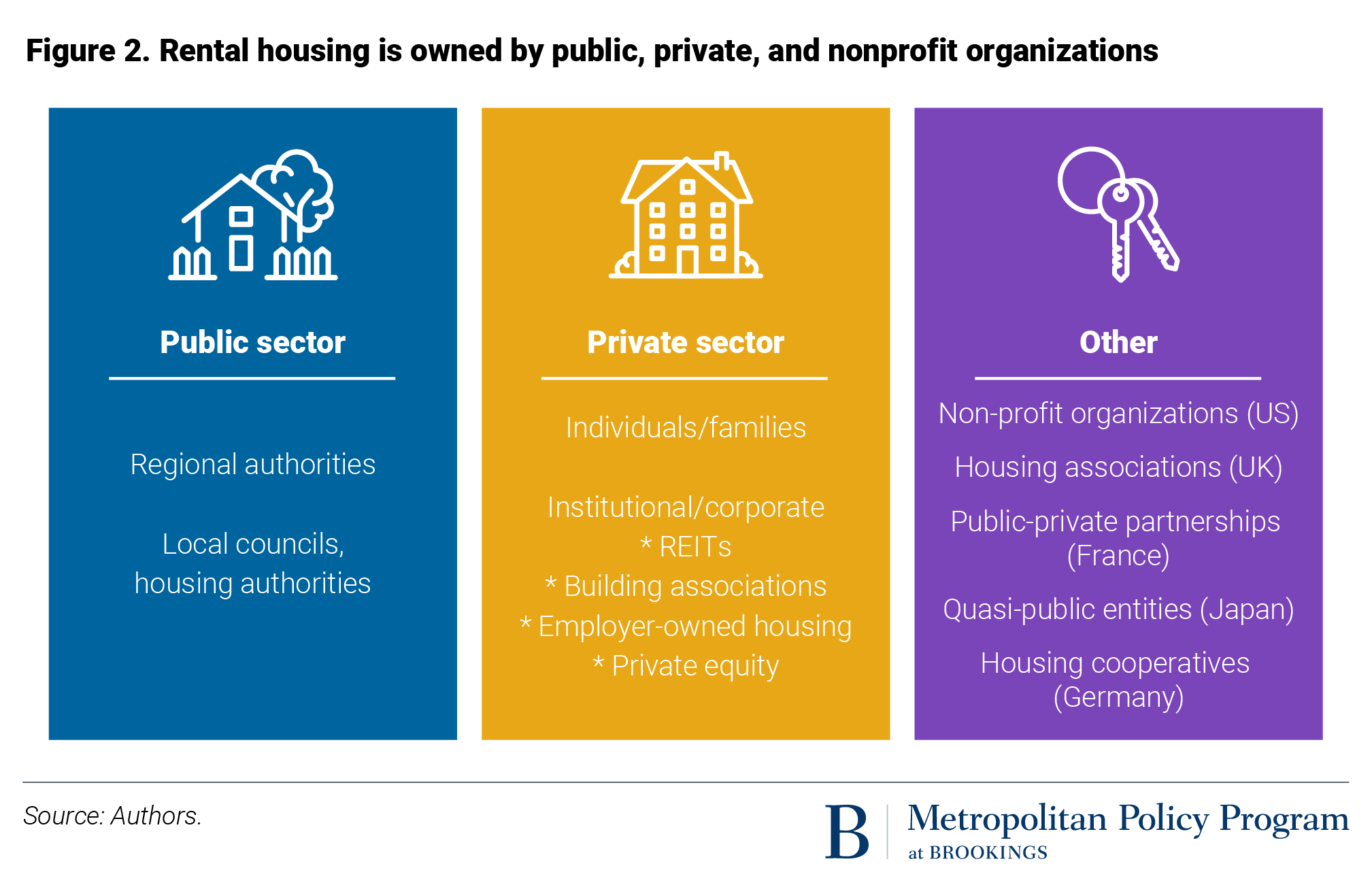

One of the most striking differences across countries is who owns rental properties. Broadly speaking, landlords can be classified as public entities, private (for-profit) firms, or other organizations (Figure 2). The share of rental homes in each of these three sectors varies widely, as do the types of entities within each.

Every country has some publicly owned rental housing (referred to as “public” or “social” housing), owned either by local or regional authorities. Social housing (owned by local councils or housing associations) makes up around 17% of the U.K.’s housing market, down from 30% in 1980. In France, public housing constitutes about 17% of the housing market and 43% of the rental market, and serves middle- as well as low-income households. By contrast, less than 5% of rental housing in the U.S. belongs to local public authorities, and all subsidized housing is less than 10% of the rental market.

Private sector landlords fall into two categories: individual and institutional owners. Individual owners make up about half of Germany’s rental market, a majority in Spain and Japan, and over 90% of the unsubsidized rental market in France. Institutional ownership is most common in the U.S., including large asset management firms, real estate investment trusts (REITs), and private equity firms. The small role of corporate owners in most countries may reflect higher risks and lower returns from those countries’ strong tenant protections (discussed below), as well as differences in corporate tax policy.

Entities that fall outside the traditional public-private categories own some portion of every country’s rental housing. Japan has national and regional quasi-public entities that provide middle-income rental housing. U.K. housing associations provide more than half of social housing there. Germany’s housing cooperatives helped address the shortage of moderately priced rental housing after WWII and still constitute about 25% of the rental stock. In the U.S., nonprofit organizations own a substantial share of subsidized housing developed under the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program.

In addition to social housing, every country provides some form of household-based rental subsidy. The share of renters who receive assistance and the total budget for these programs vary widely. France spends about $15.5 billion on tenant-based rental assistance. For a population five times the size of France, the U.S. spends only about $24 billion on vouchers. Rental assistance in Germany is guaranteed for all qualifying households, while in the U.S., most low-income households receive no assistance.

Balancing tenant protections with financial incentives to landlords can be tricky

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic worsened housing insecurity for low-income renters, tenant advocates and some U.S. elected officials were calling for stronger legal protections for tenants. Other countries’ approaches to regulating leases and landlord-tenant relationships offer some useful lessons—both in their successes and failures.

In all of the studied countries except the U.S., national laws regulate key provisions of landlord-tenant relationships, including the process for terminating or renewing leases and eviction proceedings. (The U.S. delegates landlord-tenant law to state governments.) Although the exact form of regulation differs, other countries’ national tenant protection laws make it more difficult for landlords to terminate leases, in the interest of providing renters with more stability. Multiyear or open-ended leases (no preset end date) are common in France, Germany, Japan, and Spain, while the U.S. and U.K. predominantly issue one-year leases.

Case studies of three countries—Japan, Spain, and the U.K.—highlight how strong tenant protections have periodically contributed to inadequate rental supply. Overly strict limits on landlords’ ability to terminate a lease or evict tenants—even for not complying with lease terms—increases the risks associated with investing in rental properties. Long-term leases may also restrict the ability to raise rents, further reducing the incentive to potential landlords. All three of these countries have subsequently attempted to relax national laws that were seen as inhibiting private rental markets.

Germany and France also have strong national tenant protections, but these do not appear to be as much of a deterrent to private landlords, at least when balanced with tax incentives that make owning rental housing an attractive investment for individuals.

More knowledge-sharing across countries could lead to better policies

The COVID-19 crisis has forced policymakers around the world to quickly take action in protecting the public’s health and mitigating economic damages. In the face of such enormous challenges, many brains working together are more likely to come up with workable solutions. Yet too often, policymakers across countries—and even at the local or regional level within the same country—work in isolation rather than learn from their neighbors.

Cross-country research on housing markets is not easy—it requires understanding the particular legal and financial institutions that support real estate markets and how they have evolved from each country’s unique history. Simply copying and pasting policies from one country to another isn’t feasible. But there are clearly useful lessons in how each country has tried to address long-standing housing problems, including how to provide decent-quality rental housing that is affordable to low-, moderate-, and middle-income households. We hope that international conversations among scholars and researchers—as displayed in these case studies—can help.