Executive summary

The energy sector is the largest contributor to U.S. greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Therefore, at the macro level, reducing and eliminating emissions from the energy sector is a key component of mitigating climate change to improve the lives of all. Continuing to provide affordable and reliable energy service is especially important to low-income consumers, since high energy prices are most harmful to those who can least afford to pay.

However, the costs and benefits of the clean energy transition do not accrue evenly. Thus, one must consider the local equity implications of individual energy projects. Certain communities have borne the pollution load of the country’s existing fossil fuel–based system, but these communities have also benefitted from economic growth and employment opportunities. The energy transition as a whole and individual projects must take both of these factors into consideration.

This memo explores the context of equitable climate finance in the U.S. energy transition, focusing on electricity generation and oil and gas production. It first examines the role of fossil fuels in the U.S. energy landscape, including their contribution to GHG emissions. The memo then considers how private investment flows into the energy sector. Lastly, it considers specific climate equity considerations.

- Community participation and buy-in is key to achieving project acceptance and local-level equity. Investors have a difficult time quantifying and considering issues of local equity, but they are an important source of risk that can stop projects entirely.

- Oil and gas projects seem at odds with the goal of achieving emissions reductions, but they are needed to supply the existing energy system as the transition proceeds. Existing production will almost certainly decline faster than demand for fossil fuels. Thus, an important equity consideration is how to continue to produce these fuels in ways that minimize their impact on communities and the larger environment.

- Equity issues in energy are generally related to specific projects. Thus pure-play investments in technology development have far fewer equity considerations; equity challenges can arise when those technologies are deployed in the field.

Use of fossil fuels for energy is the largest source of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions

Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels for energy account for three-quarters of U.S. GHG emissions. Since they make up the lion’s share of emissions, changes in emissions from fossil fuels drive overall U.S. emissions levels. In 2022, the most recent year of complete data from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), U.S. fossil fuel combustion emissions were 18.3 percent below their 2005 peak level.

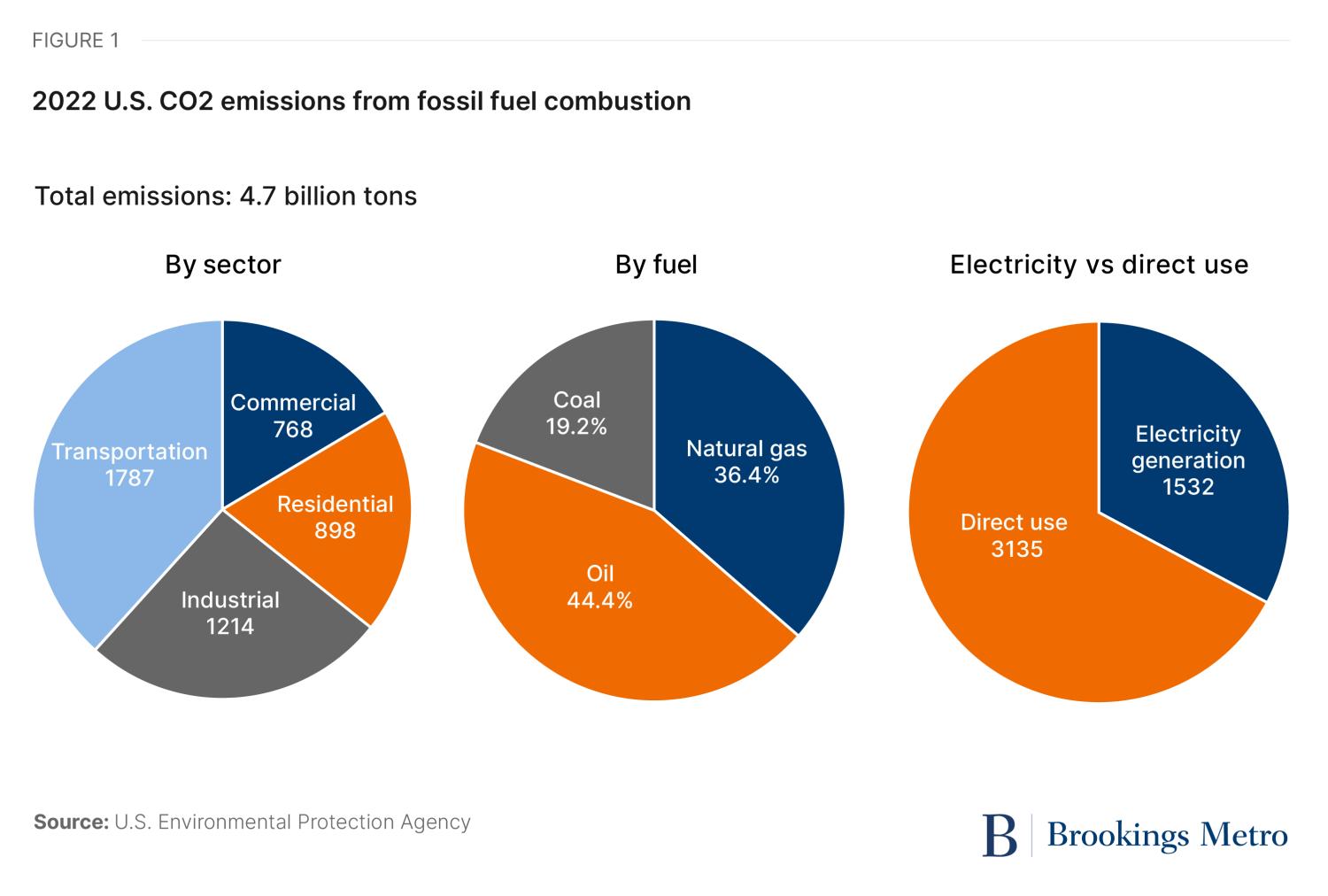

To aid understanding of U.S. energy use and GHG emissions, the economy can be divided into sectors—commercial, residential, industrial, and transportation. Transportation is the largest emissions sector in the U.S., followed by industry. Emissions can also be sorted by fuel type or by whether the heat from fuel combustion is used directly or is used to generate electricity. Figure 1 shows each of these methods of considering U.S. CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion.

Coal, oil, and natural gas are the three types of fossil fuels. These fuels are used in different ways and have different emissions of CO2 per unit of energy generated. Coal and natural gas are burned directly for heating in the commercial, residential, and industrial sectors. They are also burned to generate electricity, which is used in those three sectors. The sectoral graphic above includes direct combustion emissions and emissions attributable to electricity used in that sector. Fuels made from oil—such as gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel—are primarily burned directly in the transportation sector.

Coal has the highest CO2 emission per unit of energy, followed by oil. Natural gas has the lowest CO2 emissions per unit of energy. Coal and natural gas are burned directly in industrial and space heating applications and are used to generate electricity. Given that not all fossil fuels are created equal in terms of their GHG impact, switching among fossil fuels can have climate benefits. For example, most of the reductions in U.S. GHG emissions over the past two decades have been due to switching from coal to natural gas in power generation.

In this project, direct combustion emissions in the four sectors are discussed in the sectoral memos. The various sectors have unique justice and equity impacts, and the types of necessary investments differ and are best discussed by sector. This memo focuses on two parts of the energy sector—electricity generation and oil and gas production—that are upstream from the industries covered in the other sectoral memos.

Even though electricity generation comprises only about one-third of today’s emissions from energy use, electricity is central to achieving a net-zero economy. Transitioning electricity generation away from fossil fuels toward zero-carbon sources—including wind, solar, nuclear, and geothermal energy—will address electricity-related emissions. Additionally, electrification of energy end uses that today directly use fossil fuels, like space heating or transportation, are key pathways to reducing fossil fuel use and GHG emissions. The U.S. does not just need a zero-carbon electricity system; it also needs a bigger electricity system to supply newly electrified energy uses along with entirely new and rapidly growing sources of electricity demand, like computing centers for artificial intelligence. Development of this decarbonized electricity system and the task of electrifying more final uses of energy will be key business opportunities and areas for investment.

The world is working to transition away from oil and gas, but this transition will take time. Oil and gas production will be part of the future for decades, perhaps even longer given that they are not just used as fuels but also as raw materials for many products. The U.S. is currently the world’s largest producer of oil and natural gas. Reducing emissions and other environmental impacts from U.S. oil and gas production are key goals for mitigating climate change and ensuring equitable outcomes for the country’s population.

Trillions of dollars in investments are needed to achieve a net-zero energy system

Energy, in the form of fuels or electricity, is a key input to many other sectors. Thus, a steady supply of energy inputs at reasonable prices is key to the overall economy. Electricity prices and reliability will become even more important as the energy transition progresses and as more energy end uses become electrified. Estimates of the investment levels needed to achieve a net-zero energy system in the United States vary, but serious estimates amount to multiple trillions of dollars per year.

Investments in electricity generation and oil and gas production have an important similarity—both involve large upfront capital costs, followed by long-lived returns. Both sectors are often funded by a combination of debt and equity. Both also frequently use project finance, whereby investments are made by limited liability subsidiaries of the company involved. Such a structure securitizes the loan with the asset being built and protects the firm’s remaining assets in the event of default.

A key difference between the two sectors is that investments in zero-carbon electricity generation and in electricity transmission are often eligible to be included in green funds and to receive subsidies from the federal government. Thirty states and the District of Columbia require investment in renewable electricity through renewable portfolio standards or clean energy standards. Project finance can be helpful here, as the subsidiaries doing the investment often only includes green assets, making them eligible for green investment funds.

Investments in the oil and gas supply, while necessary, face the opposite of the green finance boost. Activists and some investor groups, like pension funds, are pushing banks to stop lending to the oil and gas sector and are encouraging funds that hold debt and equity instruments to divest. There is still plenty of capital flowing to oil and gas, but those who seek to avoid funding relationships with oil and gas may be missing an opportunity to influence the industry. Given that the energy transition will take time and that the U.S. will use those products for decades, funders have an opportunity to drive more consideration of climate and equity issues in investments. This can occur both at the macro scale in terms of minimizing GHG emissions and at the micro scale in terms of addressing local pollution and other concerns.

Regulation of revenue is another key difference to consider in financing electricity investments versus those in the oil and gas sector. Rates for retail electricity and transmission are generally regulated by state public utility commissions or by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in the case of transmission lines that cross state boundaries. Independent power producers sell wholesale power at unregulated prices, often on long-term contracts known as power purchase agreements (which are often needed to get financing for projects). Oil (and, to a lesser extent, natural gas) is sold into unregulated global markets, where prices can swing wildly over time based on supply and demand conditions. This regulatory environment means that regulated utilities tend to produce steady, but lower returns, while independent power producers and oil and gas projects can produce higher, but much more volatile, returns.

Equity in the energy transition often depends on local considerations

What does equity mean in this context?

On a macro scale, the energy industry’s climate goal is to mitigate GHG emissions by moving away from the unmitigated combustion of fossil fuels. This goal is clearly necessary given the energy sector’s large contribution to emissions. Nonetheless, the macro goal of building low-carbon projects and reducing emissions can conceal equity issues at the local and regional levels.

Defining equity in the transition to low-carbon energy is a complex undertaking, as it involves many dimensions like income, race, and access to affordable energy. In a macro sense, energy prices are a key part of an equitable energy transition, as rising energy prices are inherently regressive and affect low-income communities the most. Beginning with the lowest-cost solutions for reducing GHG emissions is an important part of addressing climate change while furthering the equity goal of keeping energy affordable. Part of considering macro-level equity may be programs that subsidize the cost of the transition for low-income consumers. This would be a policy choice, however, not a choice open to investors in energy projects.

The underlying green nature of investments in zero-carbon electricity and transmission does not mean that these investments avoid public opposition or equity challenges. On the contrary, permitting for the siting and construction of such necessary infrastructure is among the most challenging features of the coming energy transition. Renewable power installations are often large land users and can generate opposition in rural areas or other locations where people object to their aesthetics. Long-distance transmission lines are very challenging to site and permit, since they are less obviously green than renewable power generation, are large and can dominate the landscape near where they are located, and often provide little benefit to areas where they are just passing through.

Equity at the project level means assessing the local impacts of each project, dealing with the past legacy of pollution from the fossil fuel system, and providing jobs and opportunities for those affected by a particular project—especially those affected by the transition away from fossil fuels toward greener energy sources. In the best-case scenario, these goals may be aligned with the macro-scale goals. For instance, building renewable electricity generation in a location formerly occupied by a coal-fired power plant could replace some lost jobs, help maintain the tax base, and take advantage of existing transmission infrastructure in a way likely to lower costs—clearly a win for both macro-level and local equity. However, not all green investments will be a slam dunk, and the macro-scale goals of minimizing costs and GHG emissions may sometimes be at odds with local concerns.

Transmission line project demonstrates the challenges of securing local approval

The Grain Belt Express transmission line provides a case study of a project where macro-level and local equity considerations clash.

The project is an 800-mile high-voltage transmission line intended to carry enough electricity to power 3.2 million homes from wind farms in Kansas across Missouri and Illinois, connecting to the East Coast grid in Indiana. This project is clearly in the greater public interest, as it moves renewable electricity from the sparsely populated rural area where it is generated to population centers, a common feature of a grid with more renewable energy sources. But in the words of one landowner that will be affected by the power line, it will be “the single biggest, ugliest thing in northern Missouri and with it set a precedent for more to be built just like it.”

Landowners along the route opposed the line, for reasons including concerns about property values, conflict with farming equipment and methods, and a general feeling that they were not adequately consulted. One local farmer summarized his objections in this way: “It’s me working around them instead of them working with me.”

This project has been in the works since 2010, but after years of challenges in courts and state legislatures, the project finally received its final approval in Missouri in late 2023. Changes made to achieve approval included providing power from the project to communities along the line’s route and increasing compensation to landowners. But the use of eminent domain to acquire some of the easements remains a sticking point with some landowners. The fundamental problem remains that parts of the local population feel that they are suffering the drawbacks of the project without sufficient benefits. Given the way the project began, such buy-in will be difficult to achieve this late in the game.

Local participation is a key component of equity

Gaining buy-in for projects is a key aspect of project-level equity considerations. This requires project developers to engage early and frequently with the surrounding community to understand local needs and impacts through stakeholder meetings, public meetings, and efforts to work closely with community leaders on a day-to-day basis. Credibility and trust take time to develop through on-the-ground interactions; the necessity of an infrastructure investment does not mean that it will be accepted. The case study above demonstrates how a lack of engagement can derail an entire project, even if the project has clear societal benefits.

Transitioning to a greater share of electricity from renewable energy sources will require significant investment in new transmission lines, distribution networks, and other infrastructure, but space for new infrastructure is limited. Projects with small footprints, like substations, are generally easier to site than linear projects like transmission lines, which require the buy-in of many stakeholders.1 The use of existing infrastructure corridors (like rights-of-way for existing power lines or other infrastructure like railroads) can help make siting easier, but that is not always possible.

Equity issues are more than externalities

Financial institutions often see equity issues as externalities that they do not consider unless they directly affect the bottom line. However, such issues can directly affect the bottom line by delaying or canceling projects. Financers tend to focus on individual projects, without considering the broader impacts of their financing decisions. Such considerations are difficult to incorporate because they do not fit neatly into financing models. Some leaders recognize that there is a debate about whether to quantify equity impacts like project acceptance or workforce issues versus considering these impacts qualitatively.2 Additionally, industry and finance people generally do not understand sustainability, and sustainability people frequently do not understand industry and finance. This leaves a disconnect where the two camps do not speak the same language, making real consideration of sustainability and equity issues very difficult.

Scenario analysis can help facilitate discussion by raising pertinent questions and allowing various stakeholders to consider them from the same perspective. For example, a project might construct scenarios that consider how the electricity system might change over time in the project area, with varying electricity prices and infrastructure needs. This kind of analysis can increase understanding about how the project might fit into different potential futures and can allow richer discussions of potential drawbacks and benefits.

Can investments in oil and gas be equitable?

The burning of fossil fuels for energy is the primary contributor to global and U.S. GHG emissions, and the fundamental goal of the energy transition is to move away from the unmitigated use of fossil fuels. Nonetheless, some investment in oil and gas is needed, even during the energy transition, to ensure adequate supply and to prevent damaging price spikes. The International Energy Agency produces scenarios to consider how rapidly the energy transition might proceed. One scenario assumes that governments around the world will meet all their climate commitments—including those made under the auspices of the Paris Agreement, longer-term net-zero targets, and targets for access to electricity and clean cooking. Even in this scenario, current production levels would not be able to meet global oil demand, and investment in the oil and gas sector is needed. Since production in the U.S. has lower GHG emissions than the global average and is regulated better than in many areas, oil and gas production here could contribute to macro-level climate equity. (This is not an argument for endless oil and gas use, nor is it a case against the regulation of oil and gas production. It is only a statement that as long as the world is using oil and gas for some purposes, it would be best to produce it with the best standards possible.)

Local equity issues in oil and gas production can be very thorny, however, especially since this production is concentrated in certain geographic areas. These areas have borne the local pollution impact of the fossil fuel economy for decades. Ongoing oil and gas production must follow the highest environmental standards and consider local concerns about ongoing pollution and other impacts.

Reducing methane emissions from oil and gas production is an area where macro-scale and local equity converge, with benefits for both. Methane is the primary component of natural gas, which is produced on its own and also is frequently co-produced with oil. However, when methane is emitted into the atmosphere, it is a particularly potent GHG, though it has a much shorter lifetime in the atmosphere than CO2. The Environmental Defense Fund estimates that at least 30% of the climate warming the world is experiencing today is attributable to methane emissions. Minimizing methane releases is one of the most important things that can be done in the short term to slow climate change and, thus, to meet macro-level goals for climate equity. Reducing methane emissions has local benefits as well—improving local air quality and providing jobs for leak detection and repairs.

Local equity is less important in business-to-business companies

Local equity issues generally arise in project development, especially when the macro-level concern of reducing GHG emissions conflicts with local concerns about a project’s impact. But an important area for energy investments is green technology—products and services that help to reduce GHG emissions in the energy sector. Some funders focus investments on technologies that reduce GHG emissions, leaving the details of local project development to others.3 This strategy is one way to avoid the thorny considerations of balancing macro-scale and local equity. Investment in technology is crucial to achieving climate goals. However, somebody needs to use these technologies in projects on the ground. Equity considerations and risks are mostly connected to the site and local conditions, less to the technologies themselves.

Conclusion

Clearly, a low- or zero-carbon energy system is key to achieving society’s overall goal of mitigating climate change. This vast change to the current fossil fuel–based energy system naturally creates winners and losers, even as the net benefits to society as a whole are obvious. A just, and politically palatable, energy transition requires considering the needs of those with something to lose through this change. Additionally, the costs of the energy transition must be shared equitably, if not evenly. High energy prices are most harmful to low-income households, which spend a disproportionate amount of their income on basic services. An equitable outcome may require softening the cost burden on these households.

Equitable climate finance series

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Funding for this research was provided by HSBC Bank USA, N.A. The program is also grateful to the Metropolitan Council, a network of business, civic, and philanthropic leaders that provides both financial and intellectual support to the program. The views expressed in this report are solely those of its authors and do not represent the views of the donors, their officers, or employees.

-

Footnotes

- Brookings expert interviews.

- Brookings expert interviews.

- Brookings expert interviews.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).