This blog is the second in a two-part series on centering youth in education research. Read the first part here.

As youth movements have expanded across the globe and youth have stepped into prominent political and social leadership roles, there has been increased pressure to “give the world’s youth a voice” and “include student voice.” Public platforms like UNICEF’s Voices of Youth create spaces where youth can share their perspectives. Yet youth-led movements and organizations remind us that youth already have voices—and they are using them. For example, the Re-Earth Initiative calls for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers to “break the echo chamber” and to position youth as agents of change, not objects or subjects.

Achieving inclusivity, accessibility, and unity in both research and practice requires centering youth voices and disrupting the status quo of who has the power and authority to frame the narrative and speak on behalf of youth. It also requires moving away from claiming youth as token partners in rhetoric to centering youth as essential partners in practice. As noted in our earlier blog, the Brookings Center for Universal Education has been working with youth researchers to intentionally center youth in family, school, and community engagement research. This blog is a culmination of insights and learnings from this process.

The difference between giving and centering youth voices

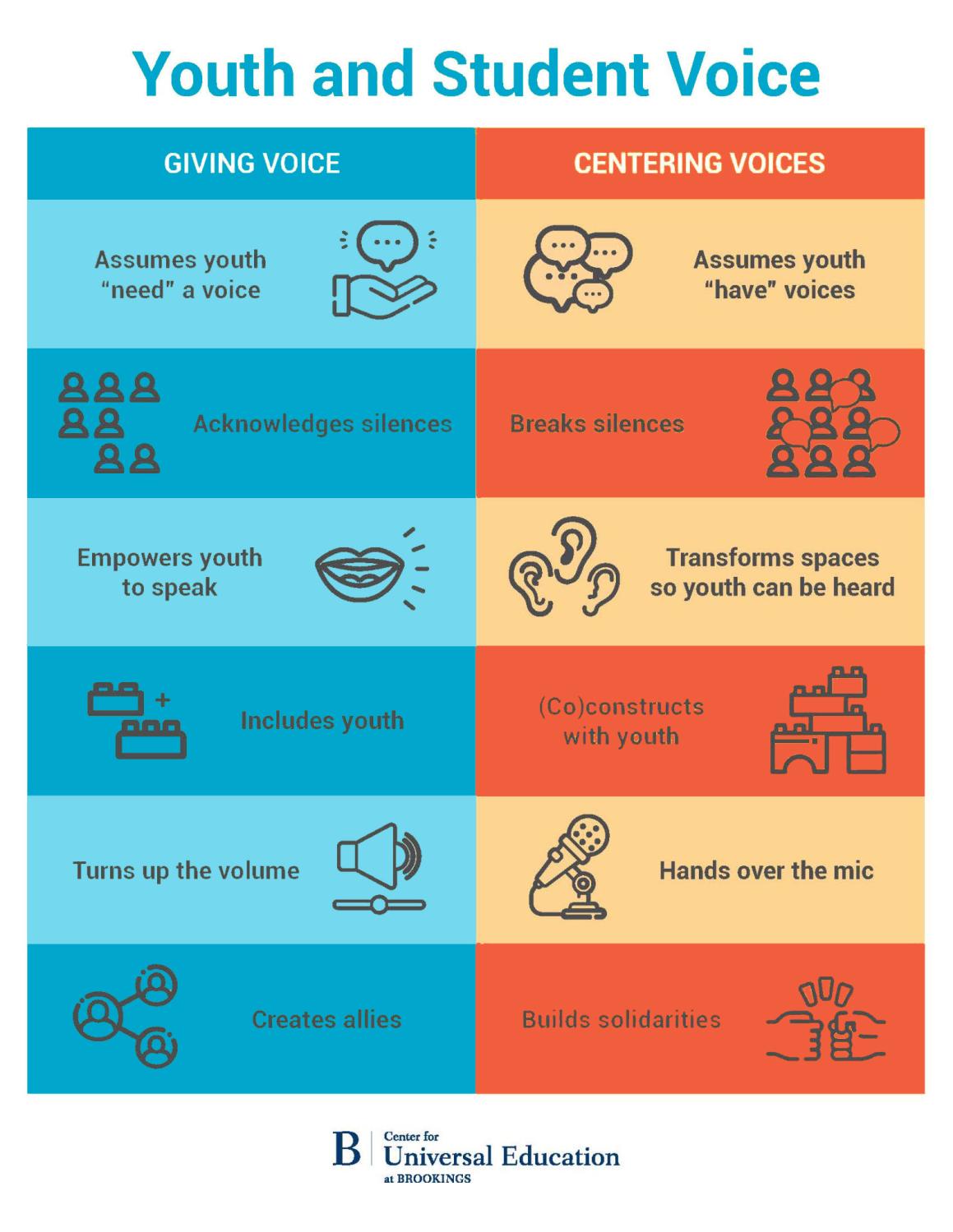

Efforts to be more inclusive of communities marginalized because of their race, gender, disability status, socioeconomic status, language, ethnicity, or other identities often use the catchphrase “giving voice.” This phrase is also overused with youth communities. This notion of “giving youth a voice” and “giving youth a place at the table” is problematic because it assumes that non-youth are granting a gift of participation to their safely guarded adult forums and spaces. Instead, centering youth voices entails breaking down the barriers to exclusion that have prevented youth from having the platforms to be heard and addressing head on the reluctance of non-youth to listen to the perspectives of young people. It is not about superficially making space at the table but reconsidering whether “the table” is the right forum for youth to participate in and to be genuinely heard. To help highlight this nuance between “giving” and “centering” voice, we created this following visual. Although presented in two columns, the intention is not to create a binary or continuum but to get researchers, policymakers, and practitioners of all ages to consider how they are involving youth in their research or practice.

Source: Emily Markovich Morris, 2023

Moving from giving to centering youth voices

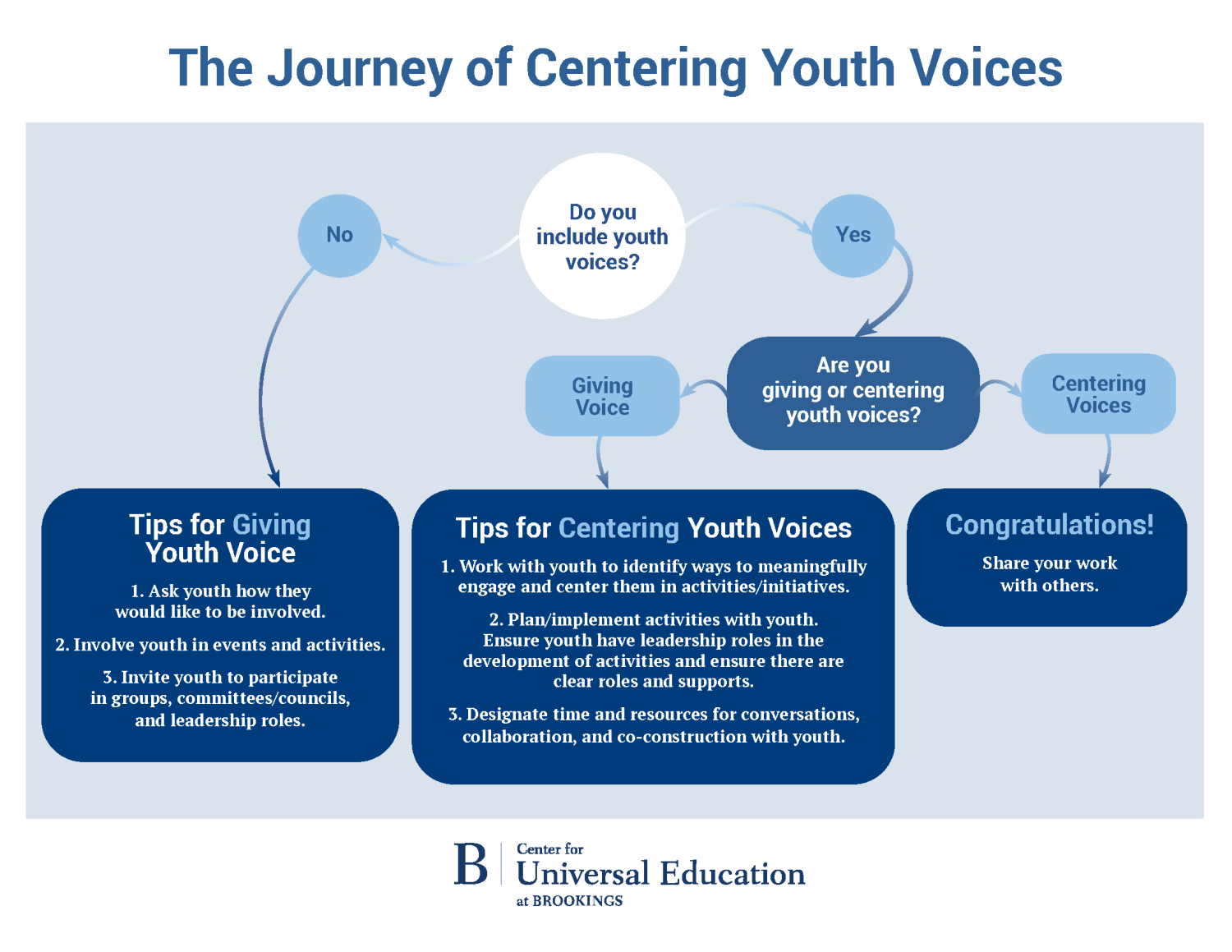

Although in some contexts starting with “giving youth voices” may be an important first step, being conscientious about moving toward the practice of “centering youth voices” helps shift research and practice power hierarchies that have tokenized youth and neglected their vital contributions to education research and practice. Below is a journey map which provides tips for policymakers, researchers, educators, and other practitioners on how to include youth voices and perspectives in their work. Examples of three teams working to center youth voices in practice are detailed below.

Source: Emily Markovich Morris and Claire Sukumar, 2023

Centering youth voices in practice

This section offers examples of what including and centering youth voices looks like in practice. Here, we will share three organizations effectively centering youth voices in different contexts.

The Foundation for Education Development’s (FED) Learners’ Council in England aims to bring and integrate youth voices into the educational policy decision making processes. The FED’s overarching goal is to promote a long-term vision and plan for education in England through authentic dialogues between learners, educators, funders, and the private sector. Young people chair and lead the council, including setting up agendas and facilitating dialogues with other youth as well as decisionmakers, such as the Children’s Commissioner who protects and promotes the rights of all children in England. Through the Council, youth build relationships with each other as well as adults in a range of sectors and roles and collectively discuss their vision for education in England and how they would like to see this vision enacted.

The Kentucky Student Voice Team (KVST) is an independent youth-led nonprofit in the U.S. that is “co-creating more just, democratic Kentucky schools and communities as research, policy and advocacy partners.” They center young people as leaders and co-leaders in policy-oriented research and public engagement, sharing youth perspectives and recommendations with policymakers, media, and the larger public. They also build intergenerational collaboration in research, where adults “can amplify and elevate student voice by serving as facilitators, guides, sponsors and supporters.” KSVT Studies include examinations of the social, emotional, and academic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic; the effects of racial and ethnic identity on learning; and what students need to feel safe, included, and engaged in their school communities. In KVST, young people constitute the majority of the leadership team, and no major decisions are made without students. They are “in the room” at all times, including for conversations related to funding and budgeting. The KVST has shown that there is a market desire for youth perspectives as their leaders are hired as contract-consultants for organizations looking to engage youth in their own practices.

In family, school, and community engagement research that our team at the Center for Universal Education has been conducting with civil society organizations in Zanzibar, Tanzania, student and youth perspectives have been central to making recommendations on partnerships. According to a leader of the youth-led research team Muhammad Said, having youth at the forefront of research on youth and students is important for four key reasons. First, it helps ensure that research is centered in the realities of young people and has credibility among youth. Second, when youth researchers interface directly with other young people, participants do not feel like there is a right or wrong response and they can be more confident speaking, particularly in an environment where children and youth are expected “to be seen and not heard.” Third, centering youth in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data helps ensure that generational and positional nuances are seen and heard, resulting in recommendations that are more relevant and responsive to student needs and their contexts. Fourth, centering youth in research opens a space for young people to grow and learn as rising leaders, and helps generate the energy, activism, and optimism that the field of education needs.

Conclusion

Harnessing youth voice is not solely setting a token place at the table or handing young people a survey to capture their viewpoints. To move toward centering youth voices in research and practice, we need to redesign the table or consider another way of sitting together as youth and non-youth. To center youth in both research and practice, adults and gatekeepers in institutional spaces must share power and break the status quo and conventional ways that youth voice has been framed and used. This requires moving beyond the practice of loaning the microphone to youth on panels at assemblies, summits, and convenings—inserting youth into adult-facilitated conversation and usual ways of working. Rather it requires giving youth the power and support they need to reflect, redesign, and revise—it means being uncomfortable with our comfortable ways of working—and trusting youth on this reenvisioning.

Commentary

Handing over the mic: The difference between centering and giving youth voices in research and practice

September 5, 2023