This blog is the first in a two-part series on centering youth in education research. Read the second part here.

Every 12th of August we celebrate International Youth Day to create awareness on youth issues impacting communities worldwide and to celebrate “the potential of youth as partners in today’s global society.” Part of celebrating this potential is engaging youth more intentionally in education research and ensuring that they are treated as essential partners and not token partners. The first in a two-part series, this blog presents three approaches to youth research as well as principles on how to be more conscientious of the role of youth in the design and implementation of education studies. The second blog will urge decisionmakers, educators, and other experts to move from the notion of “giving youth voice” to “centering youth voices.”

Types of youth research

Youth are engaged in research in different ways, whether as the subjects and objects of research or agents leading or co-leading the research. We created three categories to help researchers of all ages make informed methodological decisions and to avoid tokenizing youth in practice.

1. Youth as research subjects and objects

Youth are the subjects and objects of educational research but do not lead or co-lead the research or any part of the processes. For example, conventional youth research led by non-youth researchers who interview, observe, hold conversations with, or study youth using other methods. This includes multigenerational research where youth are among the different participant groups studied, but their interactions with other generations are not intentionally analyzed. Another example is historical research where youths’ roles, perspectives, or experiences are studied retrospectively.

2. Youth as co-researchers

Youth co-construct and co-lead the design and implementation of research with non-youth researchers. This includes intergenerational research on education, where youth work with researchers from different generations through all steps of the research process. This approach reshapes generational viewpoints and leverages the diversity between generations to create more relevant, inclusive, and equitable research. Intergenerational research can help ensure research is translated into educational policies, programs, and practices as non-youth researchers “can help open doors, facilitate introductions, share historical and institutional knowledge, break up the work into smaller, more scaffolded projects, provide funding, and advocate for students to be heard” (KnowledgeWorks, 2023, p.7).

3. Youth as lead researchers

Youth are the primary agents and leaders of research, and all phases of the research process are led and executed by youth and with youth. This includes youth-participatory action research (YPAR), where youth propose, design, and implement their own research, and are both the lead experts and the subjects of the research. Non-youth researchers are on the sidelines as advisers, mentors, or support as designated by the youths themselves. YPAR characteristically adopts a socially just perspective, aiming to empower youth by allowing them to address the questions they encounter using methods and approaches that resonate with their understandings and experiences.

Principles of youth-centered research

Youth-centered research pushes scholars, practitioners, and policymakers from doing research on youth to doing research with youth. As a youth-researcher (Omaer) and a non-youth researcher that has long worked on the topic (Emily), we argue that an important goal of educational research is to move toward youth-centered methodologies and practices that work in solidarity with youth researchers. Here are five key principles gleaned from youth-centered research to help work toward this goal, especially in cases where youth are co-researchers, such as intergenerational research.

Youth-centered research principles

- Treat youth as experts and agents, not as objects and subjects.

- Put care, relationships, and safety first.

- Build trust and collaborate with integrity.

- Create informal (check-ins) and formal ways (youth advisory groups) for youth to co-create the research.

- Use methods where youth can shape and control their narratives.

Berson, Berson, & Gray, 2019; Maynes, Levinson, & Vavrus, 2021; Markovich Morris, 2021; Tomas & Kane, 1998; Woodgate al al., 2019.

We cannot stress enough the importance of using all these five principles in practice as they are each equally critical. Positioning youth as experts helps ensure research is relevant and informed by youth experiences. Care, relationships, and safety put the individual and community above the findings, and trust and integrity are key for building relational trust among researchers. Check-ins and formal mechanisms for involvement allow youth to be continuously involved in the feedback process. Methods that allow youth to shape their own narratives—such as qualitative arts-based and narrative research methods—create opportunities for youth to develop a sense of connection to and agency over the research.

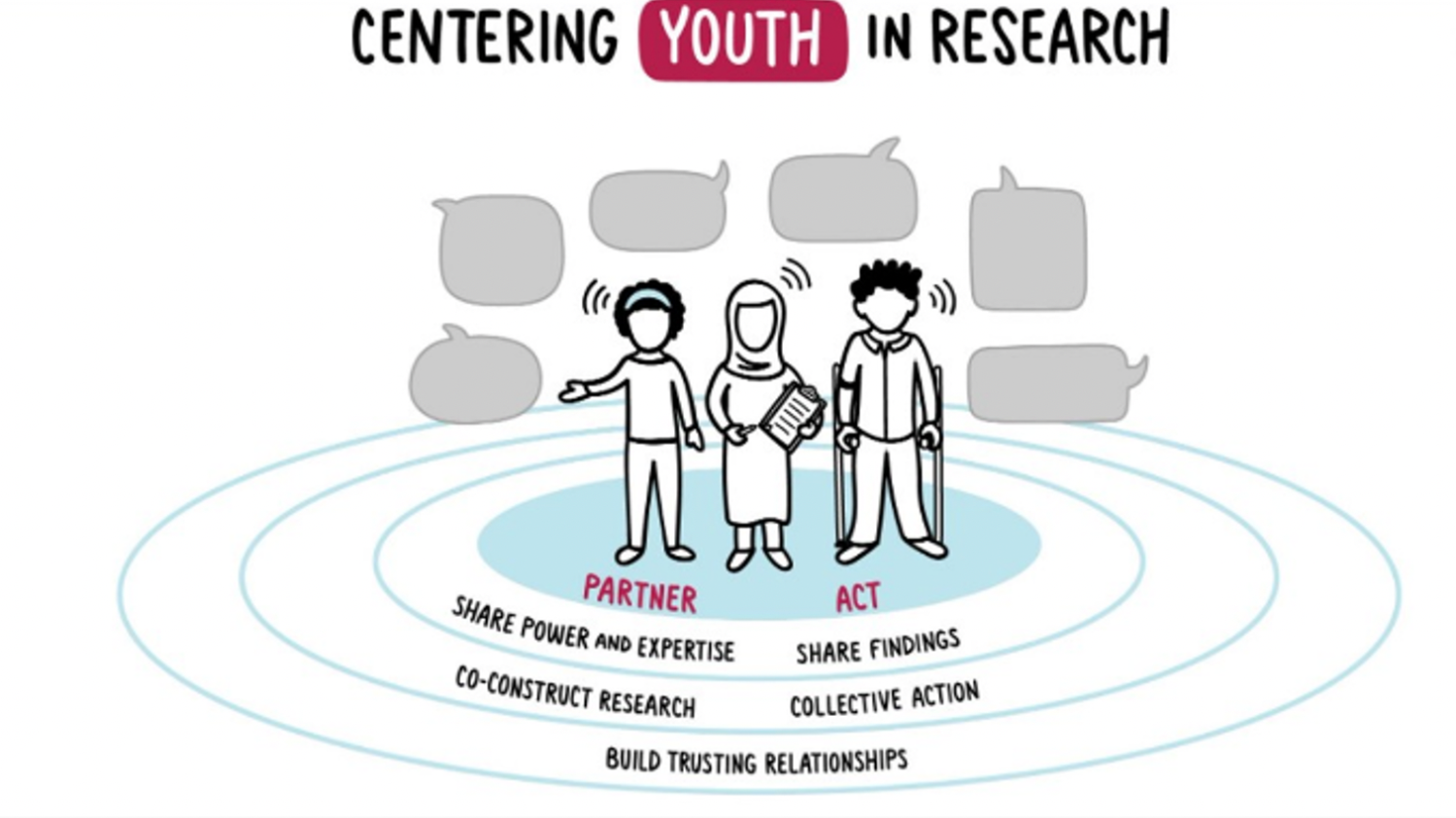

In youth-centered research, engaging youth must be intentional and meaningful. It requires non-youth researchers to treat youth as indispensable and fundamental partners and to share power and expertise in making decisions. Engaging youth intentionally and meaningfully also requires sharing findings in ways that are responsive to youth cultures—such as using videos, podcasts, infographics, and other creative media platforms—and determining how findings and recommendations can be used to improve the lives of youth.

Partnership and collective action are central to youth-centered research.

Source: Emily Markovich Morris and Emily Marko, 2023. Inspired by YPAR scholarship and principles.

Applying youth-centered research principles in practice

The Center for Universal Education (CUE) has been developing intergenerational research on family, school, and community engagement in education and we share an example of how we are moving from an approach of youth as subjects and objects to one of youth as co-researchers. In the first phases of our family, school, and community engagement methodology—the Conversation Starter Tools—we did not involve youth; we only collected perspectives from parents/caregivers and educators. We quickly realized that youth perspectives were critical to the research and began surveying students alongside their families and teachers, using a youth as research subjects and objects approach. Together with schools and civil society organizations, we shared the survey data back with schools and communities, and youth led conversations with other students on how they would like to see families and schools partner to support their learning and development. In this youth as co-researchers approach, young people framed, analyzed, and made sense of the findings with non-youth researchers—which included identifying strategies to support greater family and school partnerships.

Although we did face challenges such as getting special research permissions and protections for youth under 18, we found that when we co-designed the research approach with youth, we had better protocols for safeguarding and protecting youth. Through careful planning, we found that the benefit of inclusion of youth far outweighed the effort required to work through protocols and regulations intended to protect youth. In the next phase of our research, a youth research advisory group is being created to help determine the subsequent research design, methods, and process of the family, school, and community research. The intention is to share power and expertise and to do better at co-constructing research with young people.

Conclusion

In order to “give the world’s youth a voice” and “include youth voice” in research we need to do a better job of naming what this looks like in methodology, principle, and practice. When youth are left out of educational research, or they are positioned as mere subjects or objects, the breadth and the depth of the research are compromised. We reinforce a practice that suggests youth are beneficiaries of education systems change, but not agents of change. As youth have the most at stake in educational research and practice—and are the true experts on youth—their perspectives and contributions are fundamental. Furthermore, non-youth experts learn simultaneously with youth experts; all ages and generations grow and evolve through interactions and exchange. The solutions and recommendations proposed by youth often push the imagination of what previous generations can envision. The field of educational research stands only to gain by recognizing, valuing, and centering youth as essential partners and not token partners.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Potential or essential? Youth as partners in education research

August 11, 2023